![]()

My first ever book - order it here

|

Created: 7 June 2002. Update December 2021

Gross incompetence by the US Navy contributed to the loss, so they blamed the ships Captain. At 0014hrs on 30 July, 1945, the USS Indianapolis was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in the Philippine Sea. She sank in only 12 minutes. Of the 1,196 men on board, approximately 300 went down with the ship. The remainder, about 900 men, were left floating in shark-infested waters with no lifeboats and most with no food or water. The ship was never missed, and by the time the survivors were spotted by accident four days later only 316 men were still alive. The ship's captain, the late Charles Butler McVay, survived and was subjected to a court-martial and convicted of "hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag" despite overwhelming evidence that the Navy itself had placed the ship in harm's way, despite testimony from the Japanese submarine commander that zigzagging would have made no difference, and despite that fact that, although 700 navy ships were lost in combat in WWII, Captain McVay was the only captain to be treated thus. Recently declassified material adds to the evidence that Captain McVay was a scapegoat for the mistakes of others. In October of 2000, following years of effort by the survivors and their supporters, legislation was passed in Washington and signed by President Clinton expressing the sense of Congress, among other things, that Captain McVay's record should now reflect that he is exonerated for the loss of the Indianapolis and for the death of her crew who were lost. In July of 2001 The Navy Department announced that Captain McVay's record has been amended to exonerate him for the loss of the Indianapolis and the lives of those who perished as a result of her sinking. The action was taken by the American Secretary of the Navy Gordon England who was persuaded to do so by Senator Bob Smith, a strong advocate of Captain McVay's innocence. The survivors are deeply grateful to Secretary England and Senator Smith and also to young Hunter Scott of Pensacola, Florida, without whom the injustice to Captain McVay would never have been brought to the attention of the media and the Congress. This action, however, does not remove the conviction from Captain McVay's record. Nor would a presidential pardon. A pardon simple frees a person from punishment, but it does not clear the conviction nor the stain of guilt from that person's record. Thus, the survivors still seek a presidential order to expunge the conviction from Captain McVay's record and bring final justice to this story.

What Happened? The world's first operational atomic bomb was delivered by the Indianapolis, (CA-35) to the island of Tinian on 26 July 1945. The Indianapolis then reported to CINCPAC (Commander-In-Chief, Pacific) Headquarters at Guam for further orders. She was directed to join the battleship USS Idaho (BB-42) at Leyte Gulf in the Philippines to prepare for the invasion of Japan. The Indianapolis, unescorted, departed Guam on a course of 262 degrees making about 17 knots. At 14 minutes past midnight, on 30 July 1945, midway between Guam and Leyte Gulf, she was hit by two torpedoes out of six initiated by the I-58 a Japanese submarine. The first blew away the bow, the second struck near midship on the starboard side adjacent to a fuel tank and a powder magazine. The resulting explosion split the ship to the keel, knocking out all electric power. Within minutes she went down rapidly by the bow, rolling to starboard.

Of the 1,196 aboard, about 900 made it into the water in the twelve minutes before she sank. Few life rafts were released. Most survivors wore the standard kapok life jacket. Shark attacks began with sunrise of the first day, and continued until the men were physically removed from the water, almost five days later. Shortly after 11:00 A.M. of the fourth day, the survivors were accidentally discovered by LT. (jg) Wilbur C. Gwinn, piloting his PV-1 Ventura Bomber on routine antisubmarine patrol. Radioing his base at Peleiu, he alerted, "many men in the water". (a 3 hours delay ensued because of idiotic decision that there could be no ship there) A PBY (seaplane) under the command of LT. R. Adrian Marks was dispatched to lend assistance and report. Enroute to the scene Marks overflew the destroyer USS Cecil Doyle (DD-368), and alerted her captain, of the emergency. The captain of the Doyle, on his own authority, decided to divert to the scene. This disagrees slightly with a further report reprinted below. Arriving hours ahead of the Doyle, Marks' crew began dropping rubber rafts and supplies. While so engaged, they observed men being attacked by sharks. Disregarding standing orders not to land at sea, Marks landed, and began taxiing to pick up the stragglers and lone swimmers who were at greatest risk of shark attack. Learning the men were the crew of the Indianapolis, he radioed the news, requesting immediate assistance. The Doyle responded she was enroute. As complete darkness fell, Marks waited for help to arrive, all the while continuing to seek out and pull nearly dead men from the water. When the plane's fuselage was full, survivors were tied to the wing with parachute cord. Marks and his crew rescued 56 men that day. The Cecil Doyle was the first vessel on the scene. Homing on Marks' PBY in total darkness, the Doyle halted to avoid killing or further injuring survivors, and began taking Marks' survivors aboard. Disregarding the safety of his own vessel, the Doyle's captain pointed his largest searchlight into the night sky to serve as a beacon for other rescue vessels. This beacon was the first indication to most survivors, that their prayers had been answered. Help had at last arrived. Of the 900 who made it into the water only 317 remained alive. After almost five days of constant shark attacks, starvation, terrible thirst, suffering from exposure and their wounds, the men of the Indianapolis were at last rescued from the sea.

The impact of this unexpected disaster sent shock waves of hushed disbelief throughout Navy circles in the South Pacific. A public announcement of the loss of the Indianapolis was delayed for almost two weeks until August 15, thus insuring that it would be overshadowed in the news on the day when the Japanese surrender was announced by President Truman. The Navy, however, was rushing to gather the facts and to determine who was responsible for the greatest sea disaster in its history … who, in effect, to blame. It was a faulty rush to judgment. It is important to note at the outset that vital information pertinent to determining responsibility for the loss of the Indianapolis was not made public until long after the subsequent court-martial and conviction of Captain McVay. U.S. intelligence using a top secret operation labelled ULTRA had broken the Japanese code and was aware that two Japanese submarines, including the I-58, were operating in the path of the Indianapolis. This information was classified and not made available to either the court-martial board or to Captain McVay's defence counsel. It did not become known until the early 1990s that - despite knowledge of the danger in its path - naval authorities at Guam had sent the Indianapolis into harm's way without any warning, refusing her captain's request for a destroyer escort, and leading him to believe his route was safe.

|

| August 2020. I have been sent an email from an aviator friend of mine with regards to the PBY Catalina rescue plane. |

|

Just after midnight on 30/07/1945 the USS Indianapolis was torpedoed in the Philippine Sea by a Japanese submarine. The heavy cruiser was returning from Tinian, a tiny island in the West Pacific, where it had dropped off components for an atomic bomb. The ship sank in 11 minutes & led to the greatest loss of life at sea in the U.S. Navy’s history. The ship’s mission was classified & no one in the Navy’s chain of command missed them for four (4) days. Of the 1,200 men serving on USS Indianapolis, approximately 900 survived the torpedo attack & were left to fend for themselves w/little or no food or water for four days in shark-infested waters. By the time a seaplane spotted them & rescue ships arrived, only 316 men were still alive.

The Angels of the Sky & Water

As day four dawned for the sailors of the Indy, hope was quickly fading. Watching their friends being devoured alive by the frenzied sharks and even witnessing fights as hallucinating sailors turned on one another, it was no wonder despair was sinking in. And so, perhaps it was divine intervention, maybe it was luck, but late morning that 4th day, American pilot Lieutenant Wilbur Gwinn was flying his PV-1 Ventura Bomber when he had trouble with an aerial antenna. Handing control over to his co-pilot, Gwinn moved to the back of the plane to attempt to fix the equipment. According to Dr. Haynes, Gwinn said his neck got sore hunching over the antenna, so he stretched out in the blister, looked down, & happened to focus his eyes on the water below at just the right moment. Seeing what he later described as a big black smudge in the water, Gwinn assumed a Japanese submarine was disabled in the ocean below. Excited to finish it off, he took the controls and circled around to drop his bombs on the imagined sub. But as they drew nearer, he realized there were a large number of men bobbing lifelessly in the water. Waggling his plane’s wings to let the men below know he saw them, Gwinn radioed ahead to alert his base on the island of Peleliu. In a stroke of asinine bureaucratic idiocy, the Navy wasted three hours denying there could possibly be a ship’s crew floating in the ocean. Three hours before they ordered rescue be sent. Gwinn dropped what life jackets & canisters of water he had to the survivors, but according to Dr. Haynes the canisters ruptured on impact. Rather than immediately sending a rescue crew, the Navy ordered a single airplane to do recon. A PBY5A (Patrol Bomber, Y is a manufacturer code) Catalina Seaplane piloted by Lieutenant Adrian Marks took off from the island of Peleliu in search of the disaster site. Marks was under strict orders to look & report only, but when he arrived at the scene, what he saw made him decide to ignore those orders. As he flew overhead, he witnessed a shark attack. According to his daughter, Joan, with whom he shared his story at great length & down to the smallest detail, Marks was gripped with horror as he watched a white tip shark savagely attack & devour a screaming sailor alive. So he went against standing orders not to land or become actively involved, & turned to land his PBY on the water. |

|

|

It was a tricky landing due to the chop of the water, but he managed it by landing in a power-on stall w/the tail down & the nose up. Marks remembers rivets popping out of the PBY’s hull from the sheer force of the landing, but he did it. At 1st he headed for the groups of men, but then he realized there were individuals floating alone all over. Understanding sailors on their own were at far greater risk of being mauled and eaten, Marks taxied the seaplane along while his flight crew pulled sailors aboard. Marks’ heroic actions are all the more astounding when you realize that until one of the oil-covered survivors uttered the word “Indianapolis,” he didn’t know who he was putting himself at risk to help. It could have been, quite literally, anyone, and we were a nation at war. John Woolston speaks of how the flight crewmember lifting men out of the water was a “short fire-plug of a man” & Italian by descent. In fact, as fate would have it, the man who lifted the sailors out of the water had been a wrestler in high school & continued his body-building to that day. He was the best possible choice for a man to pull dozens of other men out of the water, and he just happened to be aboard Adrian Marks’ PBY. At one point, as the plane taxied towards a man floating alone, the rescuers realized they did not have enough time to make another pass. If they missed him on their 1st attempt and were forced to circle around, it was clear he would either succumb to the inky depths or be ripped apart by the circling sharks. The Italian reached down into the water as the plane moved by with surprising speed, grabbed the sailor under his arms, & flung him up into the air, over his own head, & into the belly of the plane. Adrian Marks later described it as if you were standing on a chair & had to reach down to the floor to pick someone up who was absolute dead weight … while the chair moved away & the man fought his own rescue. Many of the sailors in the water were past the point of delirium & thought their rescuers were Japanese or could not comprehend what was happening at all, & as a result they fought wildly. Kicking, screaming & clawing, trying to swim away & doing everything possible to avoid rescue, many men had to be forcibly wrestled into the plane. John Woolston was one of the men rescued by pilot Adrian Marks, & he remembers the moment the plane taxied by & he was jerked up out of the water with what he recounts as herculean strength. |

|

To the crew of the Indy, Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn was their Angel of the Sky & Adrian Marks was their Angel in the Water. Knowing full well he could be spotted by the enemy, Marks turned his lights on to enable distant approaching ships to locate them more quickly as he stacked the men, he described, “like cordwood”. When he ran out of room inside the plane, he couldn’t bring himself to stop. He began wrapping men in the silk parachutes on board and tying them to the fabric-covered wings of the plane to stop them from sliding off. He used every available surface, & when he finally had no choice but to stop, he had rescued 56 men (18% of the 317 survivors). One of the most amazing moments of the rescue, according to Marks, was the dehydrated sailors’ reactions while being given sips of water. There was nowhere near enough water on the PBY to give the men more than a tiny portion each, & Marks & his crew crawled from man to man, doling out tiny sips of their precious clean water stores. Not only did none of the men ever ask for extra water, but they spoke up if a crew member lost track & tried to give them a sip meant for another sailor. Marks had never before seen such loyalty & honor. Despite what had to be body-wracking pain & hellish misery from four days in the salt water, the survivors of the Indy displayed loyalty to their fellow sailors above all else. |

|

|

| The nearest ship was the USS Cecil Doyle (DD-368), a John C. Butler class destroyer escort, far smaller than the lost Indianapolis at just 306’ in length & 1,305 tons. She was a fairly new ship, her keel laid in May of 1944, and her CO, Captain W. Graham Claytor, Junior, ordered her run at full speed to the coordinates relayed to him by pilot Adrian Marks: 11°30’N., 133°30’E. Captain Claytor made this decision of his own accord in response to Marks’ call for help, saving countless lives: The U.S. Navy’s 3-hour delay in ordering rescue was still dragging on when Claytor altered his ship’s course. The Doyle arrived hours after Marks’ PBY. Had Marks failed to land & take men on board, ensign John Woolston may not have survived to tell his story. |

Survivors on Guam |

|

Upon her arrival, the Doyle began to approach Marks’ PBY in the darkness, but was forced to halt some distance away to avoid injuring or killing sailors in the water. WW II was underway, although nearing its end … thanks to the Indianapolis … and enemy ships & planes could have appeared from any direction. Despite that reality, & at significant danger to himself, Captain Claytor turned on the Doyle’s massive spotlight, in part to guide coming rescuers, but also, he said, to offer hope to the men floating in the water. For many, the appearance of the ship’s spotlight was their 1st hope & knowledge of rescue. The Doyle pulled 93 survivors out of the water & gave final rites to 21 dead sailors. She was the 1st ship to arrive on 2nd August 1945, & the last to leave the scene on 8th August 1945, after days spent searching the Pacific for sailors. If not for Gwinn, the Angel of the Sky; Marks, the Angel in the Water; Captain Claytor, the Doyle, & their crews, who knows if any men would’ve had the strength or will to survive another day. NOTE: 1,195 Sailors & Marines sailed on the final voyage of the USS Indianapolis. 879 were lost when the Indy was sunk on 30/7/1945. 316 were eventually rescued. As of 28/7/2020, the number that matters most now is 10. That’s the number of USS Indianapolis Sailors still alive today. |

|

|

Adrian Marks dies at 81 WW II Pilot who led the rescue of 56 USS Indianapolis survivors15 March 1998

|

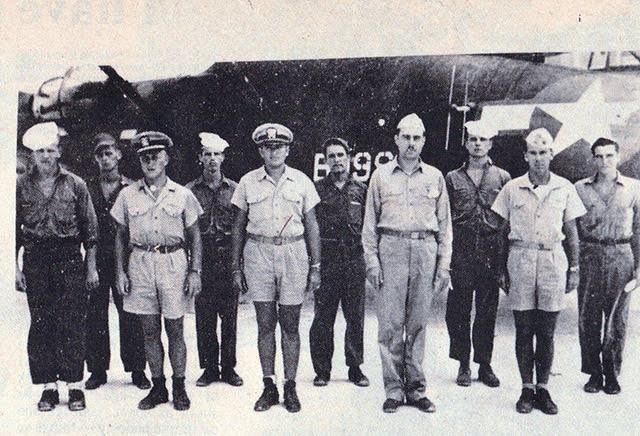

Adrian Marks & his crew in front of a PBY Catalina seaplane. |

|

Adrian Marks, a Navy pilot who rescued 56 sailors struggling in the shark-filled Philippine Sea after the cruiser USS Indianapolis was sunk by Japanese torpedoes in July 1945, died on March 7th (1998) at Clinton County Hospital in his hometown of Frankfort (IN). He was 81. Lieutenant Marks was flying a seaplane designed for landings only in calm water. He had been ordered never to touch down on the high seas. But on what he would remember as ''a sun-swept afternoon of horror,'' he disregarded his orders, risking his life & the lives of his eight crewmen, & began a dramatic mass rescue following the worst disaster at sea in American naval history. The attack took almost 900 lives. Lieutenant Marks later had the Air Medal pinned on him by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. The Indianapolis, unescorted & carrying 1,200 men, was en route to the Philippines from Guam, having delivered atomic bomb components to Tinian, when it was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-58 around midnight of Sunday, July 29th. The submarine skipper, Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, ordered the firing of six torpedoes; two struck the Indianapolis. Rocked by the explosions, she rolled over & sank in 12 minutes. Some 400 men were lost outright, but 800 others scrambled into the water as S-O-S's were radioed. No one ever heard the distress calls, so far as is known. And because of slip-ups & bureaucratic lapses, Navy commanders would not think to look for the Indianapolis even when it became officially overdue at Leyte Gulf, the Philippines. All thru Monday, Tuesday & Wednesday, the survivors of the torpedo attack … suffering from injuries, sunburn & dehydration & menaced by sharks … thrashed about in the sea. By Thursday, August 2nd, only 320 of the men were still alive. Then, at about 10AM, a Navy pilot flying a routine mission spotted figures bobbing in the water. Lieutenant Marks, summoned from the island of Peleliu, piloted the 1st rescue plane to arrive. He dropped three life rafts in the late afternoon, but one broke up when it hit the water. He then polled his crew members about whether they should make a dangerous open-sea landing that was forbidden by regulations. When they agreed, he set down his PBY5A Catalina plane, known as a Dumbo, amid 12’ swells. The plane bounced 15’ in the air after hitting the waves, but incurred only slight damage. Speaking at a reunion of Indianapolis survivors exactly 30 years later, he remembered his crew members' realization that they could not rescue everyone. ''We would have to make heartbreaking decisions,'' he recalled. ''I decided that the men in groups stood the best chance of survival,'' Lieutenant Marks said. ''They could look after one another, could splash & scare away the sharks & could lend one another moral support & encouragement.'' Lieutenant Marks' crewmen 1st picked up the men who were alone, throwing life rings attached to ropes to the men. Soon there were two survivors in each bunk on the plane, & then men were lying two & three deep in all the compartments. Lieutenant Marks later shut off the engines & put additional survivors on the bobbing wings, tying the last of the 56 men down with parachute material. And then night came. ''Even tho we were near the equator, the wind whipped up,'' he remembered. ''We had long since dispensed the last drop of water, & scores of badly injured men were softly crying with thirst & with pain. And then, far out on the horizon, there was a light.'' |

|

It was the destroyer Cecil J. Doyle (below), the 1st of seven rescue ships that were belatedly dispatched. The survivors were hauled onto the Doyle, followed by Lieutenant Marks & his crewmen, & the Doyle & other ships later fished others out of the water. The next morning, the Doylesank Lieutenant Marks' plane, now too damaged to fly again. Twelve days later, Japan surrendered, ending WW II. The skipper of the Indianapolis, Captain Charles B. McVay 3rd, was court-martialed in December 1945 & found to have left his ship vulnerable to torpedoes by maintaining a straight course rather than zigzagging. He was allowed to remain on duty, but his career was ruined. Reprimands were issued to four officers in the Pacific over the failure to mount a timely rescue operation, but these were later rescinded. Robert Adrian Marks (he did not use his 1st name), a native of Ladoga (IN), & the son of a lawyer, had graduated from Northwestern University & Indiana University Law School before the war. He was stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on 12/7/1941. He later attended flight school, became a pilot & served as an instructor at the Pensacola (FL) naval air station (NAS) before going to the Pacific. After the war, he returned to his Frankfort home … some 40 miles from Indianapolis … & opened a law practice, specializing in real-estate titles & deeds. He is survived by his wife, Elta; a son, Robert, of Bellevue (WA); three daughters, Pamela Levine of Lakeville (MA), Alexis Shuman of Enumclaw (WA) & Lynn Larson of Olympia (WA); a foster son, John Barlas of Mercer Island (WA) & ten grandchildren. Over the years, Mr. Marks never let the events of 2/8/1945, leave him. Speaking at the 1975 survivors' reunion, he paid tribute to the sailors he rescued & to all others who had undergone a shattering ordeal. ''I met you 30 years ago,'' he said. ''I met you on a sparkling, sun-swept afternoon of horror. I have known you thru a balmy tropic night of fear. I will never forget you.'' |

|

Kurzman, Dan. Fatal Voyage: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis. New-York: Atheneum, 1990. OCLC 20824775.

Newcomb, Richard F. Abandon ship! Death of the U.S.S. Indianapolis. New York: Holt, 1958. OCLC 173257, 2177577.

Lech, Raymond B. All the Drowned Sailors. New York: Stein and Day, 1982. OCLC 8668901.

Thomas B. Buell "Master of Seapower: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King"

The USS Indianapolis Monument in Indianapolis Indiana - North and South Face.Thanks to my friend Glyn Owen for the narrative of the rescue by Lt Marks and his crew. The report above was 'americanised' in writing, so I have made some alterations; there are probably more.

Some link sites have vanished, gone into the abyss.