|

|

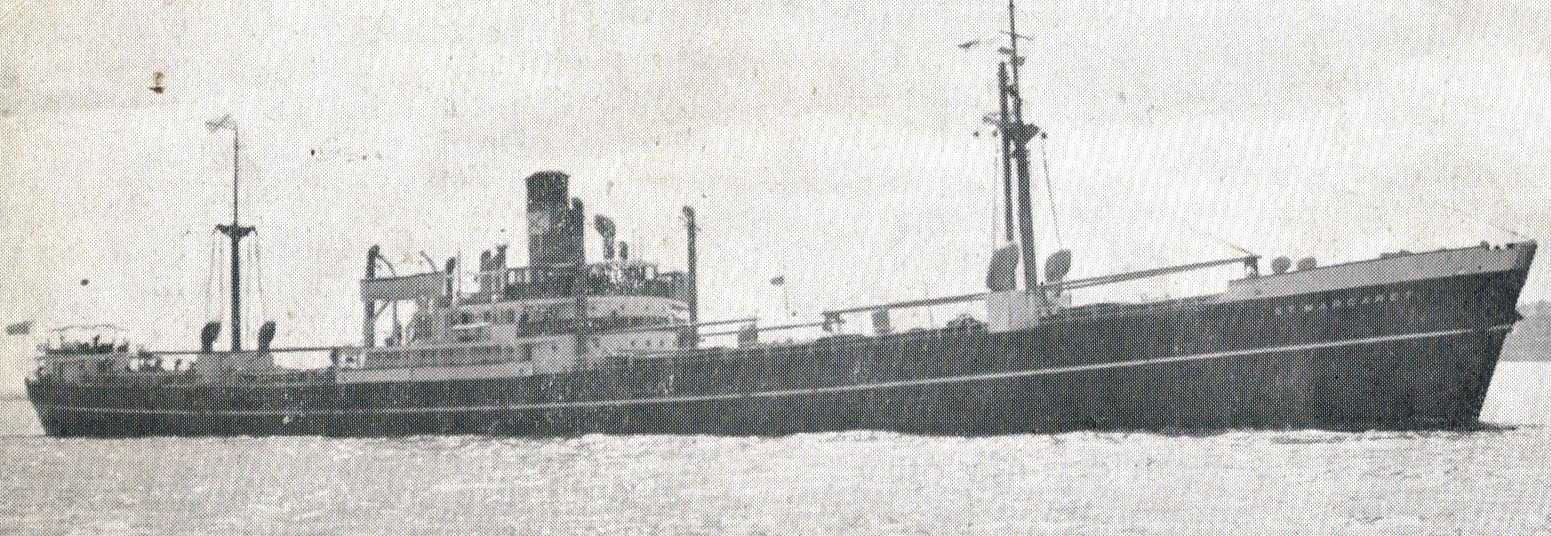

On the 2nd March 1943, the USS Hobson is recorded

as assisting in the rescue of survivors of the SS St Margaret. "Typical

of Hobson's versatile performance was her rescue of a group of

survivors from SS St. Margaret off Bermuda 2 March 1943."

- that's the whole reference. nothing else appears

on the net, - so what happened?

Judith Henry, of Carmarthenshire sent me some

papers. The ships Captain, David Sidney Davies, Judith's late uncle, was taken by the U Boat

that sank her, and incarcerated in a POW Camp in Germany. Judith has

kindly sent me a photo showing messages drawn on the camp hut rooftops

which I have copied below.

Also a copy of a Confidential letter entitled Shipping Casualties Section - Trade Division. Report

of an interview with the Chief Officer George Hamilton SS St Margaret 4312

GT. The account had been ascanned, using OCR, and some words came out

scrambled, I have altered this I have found.

|

|

|

This is an account of what happened, written by

Captain DS Davies himself, it appeared in the "Reef Knot" - the House

magazine of the Saint Line, published in 1948. The image of Capt Davies

and of the St Margaret above are also from the same publication:

February 2nd 1943, found the St Margaret, the

second of the three original vessels built for the South American Saint

Line, at Liverpool, ready to sail for South American ports. Consigned to

the Lamport & Holt Lines, the vessel was fully laden with a very superior

cargo consisting of machinery, textiles, whisky, stout, Yardley's products

etc; plus a consignment of military stores, destined to the Falkland

Islands, by transhipment at Montevideo. There were seven passengers,

including a German mother and daughter who had escaped from Germany just

before the war and now on their way to join the father in Buenos Aires.

The third lady was an ex hospital matron in charge of the hospital at

Port Stanley, Falklands Islands, when HMS Exeter of Graf spee fame arrived

after the Battle of the river Plate. She had been home to England buying

her trousseau and other things in preparation for her marriage. The

gentlemen passengers consisted of an estate manager from the Falklands,

two Belgians and a Hungarian Jew.

The vessel sailed on the a.m. tide on the 2nd

February. It was a typical winter morning, cold, windy and a threatening

sky. I well remember the Lock Gates man calling out "Good Luck" as we left

the locks. In accordance with our sealed orders, we proceeded to form up

with a local convoy, later joining the Belfast portion and finally, the

main Atlantic convoy from the Clyde. This convoy was bound for New York

and we were given our instructions to "proceed independently" at some

suitable date.

On the third morning after sailing, the weather

deteriorated rapidly, and from then onwards for almost a fortnight it was

a sequence of severe gales one after the other. Whilst normally, most of

the vessels in the convoy would be "hove to" for a considerable part of

the time, all were now making valiant efforts to remain with the convoy,

and thereby gain what protection there was. Two black balls by day and two

red lights by night, signifying vessel "not under command" were common in

all directions. Vessels in ballast were being blown almost on top of

others; laden vessels shipping heavy seas. All this, plus messages from

the Commodore, "Try and keep together. Enemy submarines in vicinity" did

not add to one's peace of mind. It almost made me wish I had stayed at

home and joined one of the guards Regiments or even the NFS. The St

Margaret made very heavy weather of it, being fully laden. The crews

quarters and passengers accommodation were flooded for days. The more

delicate sex had been granted the use of part of the Master's

accommodation, the others sleeping in the lounge.

At long last on Friday 19th February, we received

our orders to "proceed independently". We left the convoy at 9am on a

course which took us due south, through mid Atlantic. The weather had by

now eased up and, as we proceeded south, the was a marked daily

improvement. Our hopes were daily rising, as we got further from the

danger zone (we thought).

Saturday the 27th February, opened with prospects

of a good sub tropical day. At breakfast, passengers discussed how they

were going to take their trunks out on deck to dry the contents, how they

would be sunbathing etc. There was quite an atmosphere of cheerfulness,

and some relief on faces. The gunners had started cleaning their guns. We

had not heard or received any messages whatsoever of enemy activity for

several days. After breakfast the Chief Engineer was in my room and

we arranged to go around the decks and check up on what weather damage

there might be, but he was firstly going down to the Engine Room for a few

minutes.

Little did I think, when he left me, that it would be the last

time I would ever see him.

Whilst I was waiting for his return, I went to

look for the Chief Officer. I wanted all our boats which had been carried

in the Inboard position, placed outboard as the weather now warranted

this. I could see the Chief Officer on the after deck, port side, speaking

to someone, and I moved in his direction. Just as I approached him, a

terrific explosion took place, followed by huge columns of black smoke,

steam, water and oil combined, several hundred feet high, going up from

the midship part of the vessel. There was no mistaking, the vessel had

been torpedoed.

I made immediate attempts to reach the bridge,

but the rush of descending water, etc, cascading down, flooding the deck

to a depth to a depth of about eighteen inches was so strong that it made

progress very slow and difficult. Besides, I could not see more than a few

feet ahead of me. I groped my way along the ships rails and I remember the

impression came over me that the ship was sinking there and then. I

suppose if one had the time to think such an impression would not have

been a very pleasant one. I was anxious to get to the Bridge, to make sure

that the box containing the secret papers had been safely dealt with.

When I eventually

reached the Bridge and entered the Charthouse I found to my disgust and

annoyance that the box was still there. I carried it out and handed it to the

3rd Officer telling him to dump it. I will not repeat the other remark that was made. Whilst on

my way to the Bridge, I had called out Stand by the life-boats” and “See the

women in first.” From where I stood on the Bridge I could see the Starboard Big

Lifeboat in process of being loaded. The women were in. and the gunners were

also boarding it. The 2nd Officer was very ably conducting the operations. The

Port Big Lifeboat had been very badly damaged by the blast. I could see it would

not be much use, even if we could launch it at all. Because of this I called

out that as many as possible. without undue overloading, should go into the

Starboard Boat but that about a dozen men should stay behind on board to try and

get the other boats away. I then ordered the Starboard Boat to be lowered. I

also asked for a hurried Roll Call to be made.

This showed that there were four

missing, the Chief Engineer, a donkeyman, fireman and one passenger. I had by

that time verified that all communications between Bridge and Engineroom had

been completely destroyed. About then. I went down to my own quarters for a

moment having noticed that I had nit lifejacket. Inside my starboard door I

found the missing passenger, the Belgian. He was alright. but had been caught

without his lifebelt. He would not go down to his Cabin even when I assured hint

it would be safe if he hurried back. and he then proceeded to cry. It will sound

stupid. perhaps incredible. when I say that I could not help laughing. I asked

him “What the are you crying for?” I threw my life-jacket towards him and he

made record rime for the Starboard Boat and got in just as it was moving off. I

entered my bedroom for the last time, it was in a mess, the explosion having

occurred immediately underneath I picked up a Welsh Bible from the debris.

placed it inside my shirt, I had no coat on, and returned to the deck. The

reader will realize that since the explosion until now was only a matter of

minutes.

The vessel was

still on an even keel and there appeared no immediate danger of her sinking It

was certain that should she hold her own for very many minutes, a second torpedo

would strike. There was now on board, besides myself, the Chief Officer (whom I

thought had gone in the starboard boat), 3rd Officer, who worked very

bravely indeed, four sailors, the 2nd Cook, another very brave worker, and one

or two firemen. In fact, all these men were extremely cool and were ready to do

anything asked of them. As the Chief Officer was not very well I hailed the

Starboard Lifeboat to come under stern and he slid down a rope and took his

place in the boat. The next boat to get away was the small Starboard Boat, two

men were in this and were standing by “ ready to pick up the remainder should

anything happen. We still had to try and break the Belgian’s record for it. We

then tried the Port Small Boat, but this capsized and was subsequently left.

I asked the 3rd

Officer to try and get the Port Big Boat away, it would not last long I knew,

but we might be able to transfer the provisions and be glad of them at a future

date. Whilst this was being done I left the party with the view to having a look

around for the missing men. I first entered the Engineers alleyway. On looking

into the Engine Room I saw that it was completely flooded, right up to sea

level. There was much floating debris and I looked closely for any of the

missing men that might be floating around, injured. I then went along to the

Chief Engineer’s room, it was in a shambles, but no signs of life at all. I

called out several times, but all to no avail. I then walked aft, and entered

every one of the rooms calling, but there was no response.

On going forward

again. I noticed the ensign attached to the gaff halyards, lying at the heel of

the mainmast. It struck me that the “St. Margaret” should go down with her flag

flying so I hoisted the flag but when about two-thirds up it jammed and I had to

secure it in that position. I could see that the 3rd Officer and his gallant

helpers had succeeded in getting the Port Lifeboat out, and it was hanging about

half way down. They were calling on me to hurry as there would be another

torpedo soon. I once again entered the Engineer’s alleyway, went into the

Chief’s room and shifted some of the debris in case the Chief, who was a very

good friend of mine, might be underneath. It was all in vain. I at last had to

decide there was nothing more I could do. so I made for the ship’s side, the

lifeboat was now in the water and I slid down a lifeline and got into it. It was

with a very deep feeling of regret and almost guilt, that I left the “St.

Margaret.” The impression came over me that I was deserting her in her time of

trial. She was still upright and in an even keel and to me appeared very proud

and defiant, although mortally injured, and that it was only a matter of moments

before the enemy would strike again. As we pulled away I asked my comrades in

the boat to bare their heads whilst I committed our unfortunate shipmates. whom

we were leaving behind, to God’s care and mercy.

We pulled away in the direction of the other boat. We were

actually sitting in the water and it was touch and go whether we would make it

before the boat got full. When we were about two hundred yards or so away and

approaching the other boat, the second torpedo struck the vessel, also on the

Port Side. She soon commenced to list to port, then go down by the head, and in

a matter of minutes slid almost gracefully under. As she disappeared, I again

asked all in the two boats to bare their heads whilst I committed our lost

shipmates to God’s care and mercy, and asked for his care and guidance for the

remainder of us in the lifeboats. I should have said that on approaching the

other boats, we had to abandon the boat we were in as it was completely swamped.

I entered the Starboard Lifeboat. Soon after the old “St. Margaret" had

completely disappeared, a periscope was observed and a submarine surfaced and

made for the boats. When a short distance away, the Commander started howling at

us to come alongside. I say “howling” as that is the only way to describe it. He

was exactly as if mad. As we got nearer, I observed that we were covered by many

guns of different calibre and wondered what was going to happen next. The first

to be called to board the Submarine was the 3rd Officer, he wore a badged cap.

After asking some questions, the Commander asked for the Captain. I stood up and

was ordered to board the submarine. The Commander spoke reasonably good English

and had by now calmed down a little. He apologized for having to leave the

ladies in the boats, and said that I would be going with him to Germany. He

said, “Meeting you like this would be very romantic, if it was not for the

circumstances.” Thus commenced a journey on board what I was later to find out

was the Deutsch Unterseeboot U66. under the command of Captain Markworth, but

that is another story.

(Thanks to Tricia, for this information).

|

This is a scan of a photocopy, hence poor

quality

|

She sailed from Liverpool on February 2nd 1943

with convoy ON165, the convoy proceeded without incident (See (1) below) and dispersed on

19th February 1943 to sail independently. Here is the transcript of

the letter. I tried to scan it but microsoft word scanner does not like

WW2 typed paper!

|

|

Confidential DV

T.D. /139/1757

Shipping Casualties Section

- Trade Division

Report of an Interview with

the Chief Officer - George Hamilton

SS St Margaret - 4312 GT

Convoy ex ON 165

Sunk by two torpedoes from

U boat, 27th February 1943

All Times are ATS

(+ 3 hours 16 minutes GMT)

Chief Officer Hamilton

We were bound from Liverpool to

the River Plate with 6000 tons general cargo, armed with 1 x 4"; 1 x 12

pdr; 2 Oerlikons; 2 twin Marlin, 4 PAC Rockets and Kites. Our crew

numbered 43, including 5 Naval gunners, and we carried 7 passengers. Of

our total personnel, two were injured and four are missing. We carried

approximately ninety bags ordinary mail stowed in no 5 'tween deck; these

went down with the ship, and there is no chance of compromise. We also had

on board one bag special mail, which was put in the Confidential Book Box,

and thrown overboard; again, there is no chance of compromise. The

confidential Books and Wireless Codes were thrown overboard in weighted

boxes. Degaussing was off.

2. We left Liverpool at 0800 hrs

on February 2nd in convoy ON 165 and proceeded without incident until

Friday 19th February when the convoy dispersed, and we proceeded

independently. On 25th February a message was received reporting a

submarine operating in the area, approximately 345 miles SE of our

position. At 2100 on the 26th, a further message was received, but owing

to some misunderstanding in was not deciphered until the middle of the

watch, when it was found to read "if not south of position ....... alter

course immediately, and make for St Thomas. If south of this position,

ignore this message". When this message was deciphered, 0420 on 27th

February, we were making for Pernambuco to refuel, and we had insufficient

fuel to reach St Thomas. The Captain therefore decided to carry on the

course of 180 degrees to make Pernambuco.

3. At 0942 on 27th February 1943

when in position 27 38N, 43 23W steering 180 degrees (true) at a speed of

9 and one half knots, we were struck by a torpedo. There was an east wind,

Force 3, moderate sea with a heavy SE swell. The weather was cloudy, fine

and clear, with good visibility.

4. One of the apprentices saw the

torpedo break surface, as it was approximately six points from the box,

but thought it was a porpoise. It struck on the port side in the engine

room, with a very violent explosion, and a flash. A tremendous column of

water was thrown up, flooding the after deck. The engine room flooded to

the cylinder tops immediately, and the engines stopped. The main wireless

was completely destroyed. The deck did not not appeared to be damaged, but

the two ports boats, which were swung invoard at the time, were damaged.

The ship settled on an even keel, but did not list. The Captain ordered

"abandon ship" and No 3 boat got away in four minutes with 25 people,

including all the passengers. The No 1 lifeboat, which was cracked and

leaking badly, was lowered with seven or eight of the crew in it. Both

port boats were lowered, but filled on becoming waterborne. No rafts, two

rafts having previously been washed away through stress of weather.

Everyone was clear of the ship by 1010. Our wireless operators sent out

distress signals for 15 minutes, using the emergency set, before

abandoning ship and although the emergency set radiated satisfactorily, no

answer was received. The boats wireless set was placed in No 3 lifeboat

with the receiving set.

5. No 3 boat was the only really

seaworthy lifeboat, and contained 25 people, the remaining survivors being

distributed between No 1 boat and two rafts. I transferred provisions and

water from the waterlogged No 4 boat to a raft then set it adrift. After

trying to effect temporary repairs to No 1 boat, we found it impossible to

stop the leak, owing to the planks being split in the bilge streak, so

after removing the provisions to the raft, this boat was also cast adrift.

6. At 1045, the vessel was struck

by a second torpedo on the port side, in No 3 hold. This was a very

violent explosion, which caused cascades of water to pour through the

ventilators, the ventilator covers being blown off. We did not see a flash

or flame. At the time the boats were about 2 cables away, and we watched

the ship sink at 1055, vertically, bow first, with her stern out of the

water.

7. Shortly after the ship sank,

the submarine surfaced and closed the lifeboat, which contained the

Captain, 2nd Officer, all the passengers and some of the crew. The Captain

and 2nd Officer were taken on board the submarine and questioned. After a

time. the 2nd Officer was sent back to the lifeboat, but the Captain was

kept on board the submarine as prisoner of war. The submarine then closed

my raft, and I was taken on board to be questioned. The Commander asked me

where we were from, and were bound, but I refused to give him our exact

destination, saying that we were bound from England to South America. All

the time that I was on board, I was covered by bren guns, and after the

Commander had finished questioning, one of his crew took a number of

photographs of me. I was then ordered back onto the raft.

8. The submarine was obviously a

German of about 500 tons, and of the U-33 class (type 9C U-66 - mk) It

looked quite new and I could see no signs of rust or seaweed. I noticed

one gun forward, and a small AA gun mounted on the conning tower. A

Swastika was painted on the conning tower with a wolf through it. The

commander was tall, lean, dressed in a rather shabby khaki uniform, and

wore a red beard. He seemed very fit. I noticed that he spoke poor

English. The crew all worse long khaki trousers, in an equally shabby

state of repair. The Commander took our boats wireless transmitting set

from the lifeboat, together with a few tins of provisions from my raft.

Whilst I was in the conning tower, a Lieutenant asked survivors on the

raft for some cigarettes, for which he gave them in exchange some

cigarettes of a very inferior quality, of German manufacture. The

submarine then steamed away on the surface.

9. After this, I transferred to

the lifeboat to take charge, taking the two rafts in tow. I set sail at

1400, and steered a SS Wly course for St Thomas, which was approximately

1230 miles away. The (here some words are

missing from the copy).....

each raft carried 10 gallons of

water. We had a supply of smoke floats, rockets, red flares; the lifeboats

had a red sail and there were yellow protection suits. There were now 26

in the lifeboat, ten on one raft, and nine on the other. I put

everyone on very short rations, in view of the distance from land, a

typical meal being 1 and one half ounces of water, 3 horlicks tablets and

2 spoonsful pemmican.

10. We sailed through the night,

making about 1 knot, but at 0300 on the 28th the tow rope parted, and the

rafts broke adrift. I waited until daybreak before connecting them up

again, owing to the heavy swell, as I wished to avoid damaging the boat,

the rudder having already been damaged by the raft, necessitating lashing

the gudgeons to the pintles. At 0530 I connected up again and set sail. I

realised that even given the most favourable conditions, it would take 50

days to reach land, so I suggested to the crew that the rafts be cast

adrift, and for the boat to carry on independently, as there would be a

better chance of being picked up. The crew did not favour this suggestion,

so I shelved it for the time being, and carried on as before. During the

course of the day, one of the rafts showed signs of breaking up, so it was

necessary to transfer the men from it into the lifeboat. After removing

the stores, I cast this raft adrift. There were then 35 in the boat, with

ten men on the remaining raft; the lifeboat was very overcrowded, and our

limbs soon became stiff, due to the cramped conditions. I feel very

strongly that the lifeboats have not sufficient space for the numbers of

persons allocated to them.

11. At 0500 on 1st March, some of

my crew reported having seen aircraft, and although I did not see anything

I fired three rockets, and used three smoke flares, and several red

flares. Of course, we received no response to these signals, and I

considered the plane existed only in the imagination of those who reported

having sighted it. The following morning at 0700, a single aircraft was

sighted a great distance away in the SE'ly quarter, followed 10

minutes later by a second plane. I again sent up several distress

signals but after being in sight for a quarter of an hour both planes

disappeared without seeing us.

12. Shortly afterwards, another

aircraft was seen in the NE'ly quarter and appeared to be closing us, so I

fired our remaining rockets, which succeeded in attracting the attention

of this aircraft, at a distance of at least 10 miles. The plane flew over

the boat and gave a recognition signal, at approximately 0745, then flew

away. I thought it would take some considerable time for a rescue craft to

reach us, but at 0900 several funnels and masts were sighted to the NE. I

now ordered the motor to be started, and lowered sails on the raft and

lifeboat. I had deliberately reserved the petrol for such a purpose. When

the ships came into full view we recognised them as United States

warships. I manoeuvred the lifeboat and raft to the lee side of the

American Destroyer Hobson, and at 1003 everyone was taken on board, after

having sailed only 65 miles in 4 days. We were rescued in position 27 17N,

44,34W. The lifeboat and raft were destroyed by gunfire.

13. The Hobson landed us at

Bermuda on Friday March 5th. The crew were put on board an HM Ship on

March 15th and were landed at Portsmouth on March 22nd.

This is followed by a footnote

added much later to the bottom of page 3:

Distribution

C in C Western Approaches

DPD (Cdr Dillon Robinson)

SBNO Western Atlantic

DID (Cdr R Lister Kaye)

IMNG

NID 1/PW

DTD

NID 3/PW

DTD (DEMS)

NID (Cdr Winn)

D A/SW

Lieut Kidd USN

DTSD

DNO (London)

DTMI (Lieut Read)

DNC (Bath)

DSD (Lieut Thomas)

Files

Saint Margaret 4312 tons.

This ship was sunk in position 27

38N 42.23W on 27th February 1943. She was sailing independently at the

time. The submarine involved was U-66, Kapt Lt Markworth. The log gives

the time of firing the torpedo as 1731. Log book also reports that they

took the Captain of the St Margaret aboard as a prisoner.

Markworth was eventually wounded

by aircraft attack when returning from a patrol. 3 crewmen were killed and

8 wounded. Date was August 3rd 1943. He did not go to sea again.

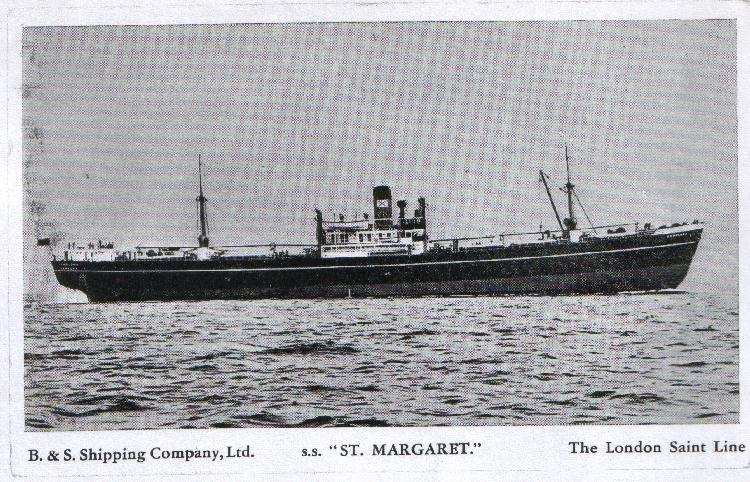

|

Type 9C, similar to U-66

|

|

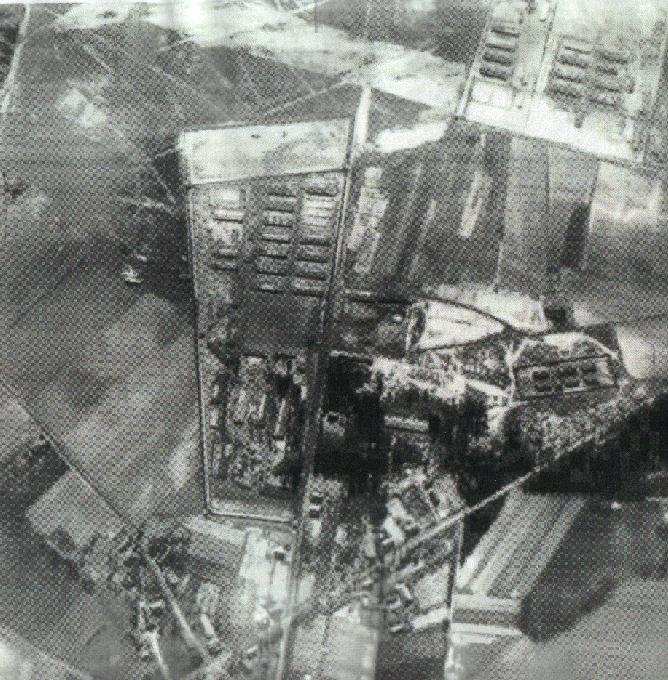

Captain David Sidney Davies was held in the

prison camp shown below. On the rear of the original photograph he wrote:

"An aerial view of a Prisoner of War camp I

served in for a long period. This was taken a few days before our release

by the 2nd Armd Div. The Welsh & Scots Guards overran our camp at 1030 pm

27th April 1945. Noswaith byth i gofio

- (Welsh - An unforgettable night).

Note the signs painted on the roof POW Still Here. This was on account of

the bombing.

This is an enlargement of this image:

U66 (circled left) and U117 under attack August

3rd 1943

Aug 3, 1943 U-Boat 66 On Aug.

3rd a patrol team came upon U-66 at a point 475 miles WSW of Flores. The

Skipper, Capt./Lt F. Markworth was headed home after 14 weeks and 2 kills off

the east coast.

(One of which was, of course,

the St Margaret) Wildcats

strafed and wounded the deck officer and he ordered the boat to dive. The

captain came up the hatch and belayed the order and guns were manned.

Avenger

pilot, LT(JG) Richard Cromier, (USNR, VC-1) encouraged the boat to dive with two

depth charges followed by a FIDO which missed. Markworth surfaced again to fight

and was wounded so his next in command took the boat down. That night, he

reported to Adm. Doenitz and was told to make contact with U-Boat 117 for

refueling and assistance.

Aug 7, 1943 U-Boat

117 On Aug. 7th LT(JG) Sallenger, USNR, spotted two subs on the surface west of the Flores,

steaming parallel and about 500 yards apart. Without fighter cover he dove down

sun and made a straddle on U-66 and gave a few machine gun blasts on the

deck of the milch cow, U-117. After radioing the

Card for help he

stayed out of range for about 25 mins when three more planes arrived.

U-66

started to submerge, Sallenger dropped down again to drop a FIDO while flying

through a hail of fire from U-117. This U-boat had the new German

anti-aircraft guns and Sallenger reported that they were "rotten", all around

but no hits. Unable to submerge, U-117 was a sitting duck for the two

Avengers. The two assisting pilots were LT Charles Stapler and LT(JG) Junior

Forney. U-66 escaped again from the

Card group but was sunk by

another Task Group a few months later. Source:

http://www.navsource.org/archives/03/cve-11/011u.htm.

Fate of the U-66:

Sunk 6 May, 1944 west of the Cape Verde Islands, in position 17.17N, 32.29W, by

depth charges, ramming and gunfire from Avenger and Wildcat aircraft of the US

escort carrier USS Block Island and by the destroyer escort USS Buckley. 24 dead

and 36 survivors. Source:

http://uboat.net/boats/u66.htm

Its been a long long time since I had

anything to update on this page, but I got this email April 26th 2012.

My father served his

first year of apprenticeship aboard the SS St Margaret on her Maiden Voyage. He

later rejoined the ship about ?1940. His story goes on rejoining the ship, “The

St Margaret scarcely looked the same, peacetime colours had been black hull with

white stripes from stem to stern, white superstructure, red funnel with black

top and shining brass and gleaming varnished brightwork. Now she was wartime

grey from stem to stern, from truck to waterline. And the ugly shape of a four

inch gun was being bolted down on the steering house. The St Margaret had half

a dozen Canadian 0.300 Ross Rifles for, supposedly, sinking floating mines. The

gun was Japanese of 1912 vintage with separate ammunition.” Dad went into some

detail about how these guns worked, or didn’t work, as the case may be, but what

is interesting is that he started his four year apprenticeship on this ship and

it was on this same ship when his Indentures expired and was signed on the

ships articles as Cadet AB. My fathers name was Frederick Edgar Barley.

Thanks Regards Ellis Burgess.

|

| |

|