333rd Field Artillery Battalion

Partly copied from War History Online, with permission - the rest can be read on the link at the base of this page

| Eleven men from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion were taken prisoner after taking refuge in a Belgian village. They surrendered peacefully to a squad from the 1st SS, and marched out of the village. Upon arriving in a large field along the main road, the men were beaten and finally executed. After the battle, the massacre was investigated but in the whirlwind of post-war politics, it was quickly forgotten. Why was such a horrific act brushed aside? Was it race? All of the men were black. Was it Cold War politics? Taking revenge might anger our former enemies. The reasons are many but when one goes back to examine the massacre, a light begins to shine on the much forgotten role of black American troops during the conflict. | |

|

On December 16, 1944, the Germans launched their last great offensive against the Western Allies through the Ardennes Forest of eastern Belgium. It would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. Three German Armies attacked a long a 50-mile front. American troops manning the line were thrown into confusion. Even the high command was stunned. Stabilizing the line was first priority and many of the units available were African American. One of them was the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion. From the battle emerged a multitude of heroes and villains. The brutality rivaled that of the Eastern Front; no quarter was given. Incidents like the Malmedy Massacre became well-known. On the afternoon of December 17, 1944, over 80 GIs who had been taken prisoner were gunned down by men of the 1st SS Panzer Division. Some escaped to spread the story, which led to a steely resolve on the part of American troops. But later that night another massacre occurred that received little attention during or after the war. |

|

Searching for a sniper June 10, 1944, Vierville-sur-Mer |

The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion (155mm), like most African-American artillery battalions in the segregated Army, was a non-divisional unit under the command of its Army Corps, in this case, VIII Corps. Two or three of those battalions would be configured into a “Group.” By coincidence, the 333rd’s group was also called the 333rd. It had at various times, both white and black units. At the start of the battle, the group also consisted of the 969th FAB (African American) and the 771st FAB (white). The role of the Corps artillery was as supplemental fire support for the infantry divisions who had their own organic artillery battalions as well. Most of the corps units in the European Theater of Operations used the 155mm howitzer (& Long Tom version), 8 inch howitzer or 4.5 inch gun. Situated along the Andler-Schonberg Road, east of St. Vith, Belgium, the 333rd FAB had been in position since early October. After the departure of the 2nd Infantry Division the first week of December, it was nominally attached to the 106th Infantry Division who had replaced the 2nd in the sector. The 106ths infantry regiments were spread out along the Schnee Eifel ridge a few miles east and south of the 333rd. Two observation teams were posted in and around the German village of Bleialf. A liaison officer, Captain John P. Horn, had been assigned to the neighboring 590th Field Artillery of the 106th Infantry Division. |

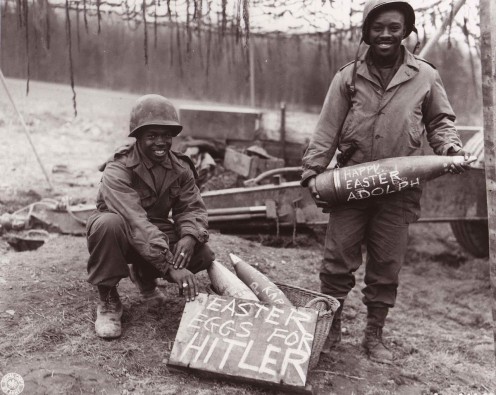

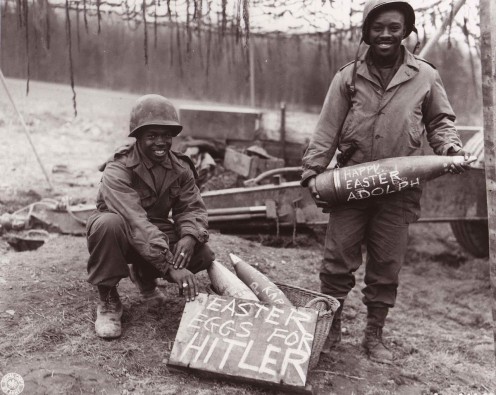

| The 333rd had something many of their neighboring units did not have: combat experience. Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Harmon Kelsey, a white officer, the Battalion had been in the field since late June ’44, when it landed at Utah Beach. It fired its first shots just hours after arriving. After helping to chase the Germans out of France all summer, it arrived on the German border in late September. It was attached to the 2nd ID as it moved into the Ardennes in the early fall. Its main gun was the standard M114 155mm howitzer (towed), and it had the standard table of organization with three firing batteries along with a headquarters battery and service battery. Despite the segregation of the era, some of its junior officers were black. The Battalion had an impressive record, once firing 1500 rounds in a 24 hour period and later capturing a village in France. And for once, a black unit received some recognition when Yank Magazine ran an article devoted entirely to the Battalion in the fall of 1944. |

A soldier assigned to the 14th Armored rounds up German prisoners. |

|

Normandy Beaches, helping a fellow soldier |

|

The following soldiers were murdered at Wereth: 17 December 1944

May they rest in peace. |

| A french german sympathizer in the village informed on them. Sometime later, a patrol from the 1st SS approached the house, and the GIs surrendered peacefully. They were led out of the village to a small, muddy field. Over the next several hours, all eleven were tortured, beaten and shot dead. In January, a patrol from the 99th Infantry Division was directed to the site by villagers. What they found was horrific. Legs had been broken. Many had bayonet wounds to the head. Skulls crushed. Even some of their fingers were cut off. Army investigators were called to the site along with signal corps cameramen to record the grisly find. |

Minesweeping France 1944 |

| Details can be also be found here: http://www.wereth.org/en/history |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_SS_Panzer_Division_Leibstandarte_SS_Adolf_Hitler |

| http://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/forgotten-massacre-story-333rd-field-artillery-battalion-wereth-11-cj-kelly.html | |