|

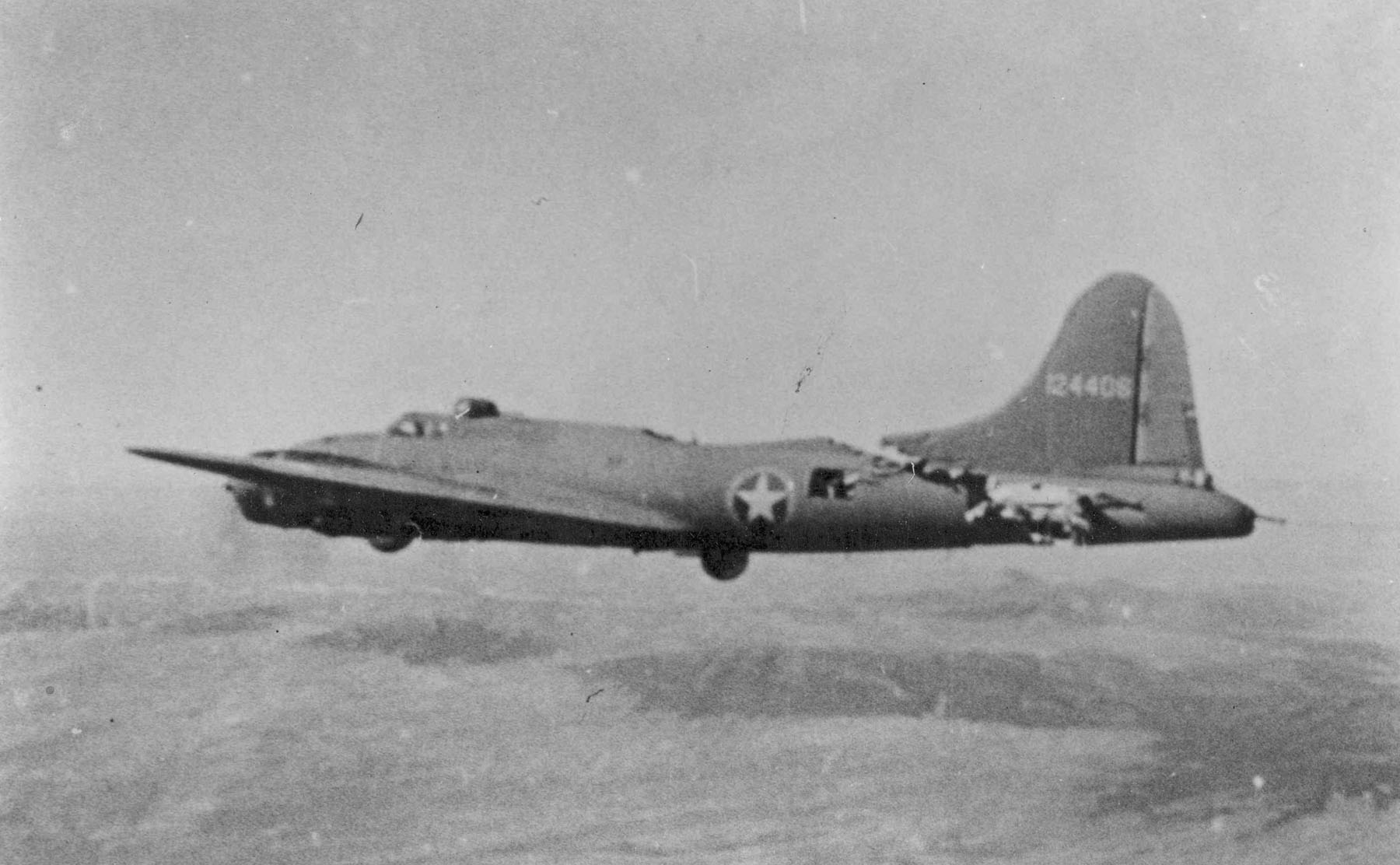

Look carefully at the B-17

and note how shot up it is - one engine dead, tail, horizontal stabilizer and

nose shot up. It was ready to fall out of the sky. Then realize that there is a

German ME-109 fighter flying next to it. Now read the story below. I think

you'll be surprised.

Charles Brown was a B-17

Flying Fortress pilot with the 379th Bomber Group at Kimbolton, England. His

B-17 was called 'Ye Old Pub' and was in a terrible state, having been hit by

flak and fighters. The compass was damaged and they were flying deeper over

enemy territory instead of heading home to Kimbolton.

After flying over an enemy

airfield, a German pilot named Franz Steigler was ordered to take off and shoot

down the B-17. When he got near the B-17, he could not believe his eyes. In his

words, he 'had never seen a plane in such a bad state'. The tail and rear

section was severely damaged, and the tail gunner wounded. The top gunner was

all over the top of the fuselage! The nose was smashed and there were holes

everywhere.

Despite having ammunition,

Franz flew to the side of the B-17 and looked at Charlie Brown, the pilot. Brown

was scared and struggling to control his damaged and blood-stained plane.

Aware that they had no idea

where they were going, Franz waved at Charles to turn 180 degrees. Franz

escorted and guided the stricken plane to, and slightly over, the North Sea

towards England. He then saluted Charles Brown and turned away, back to Europe!

When Franz landed he told

the CO that the plane had been shot down over the sea, and never told the truth

to anybody. Charles Brown and the remains of his crew told all at their

briefing, but were ordered never to talk about it.

More than 40 years later,

Charles Brown wanted to find the Luftwaffe pilot who saved the crew. After years

of research, Franz was found. He had never talked about the incident, not even

at post-war reunions.

They met in the USA at a

379th Bomber Group reunion, together with 25 people who are alive now - all

because Franz never fired his guns that day.

Research shows that Charles

Brown lived in Seattle and Franz Steigler had moved to Vancouver, B.C. Canada

after the war. When they finally met, they discovered they had lived less than

200 miles apart for the past 50 years!

Another B17 Story

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OAPgo1iUvM&feature=youtu.be

(copied with permission)

Flying back over the desert to its base in Biskra, Algeria.

|

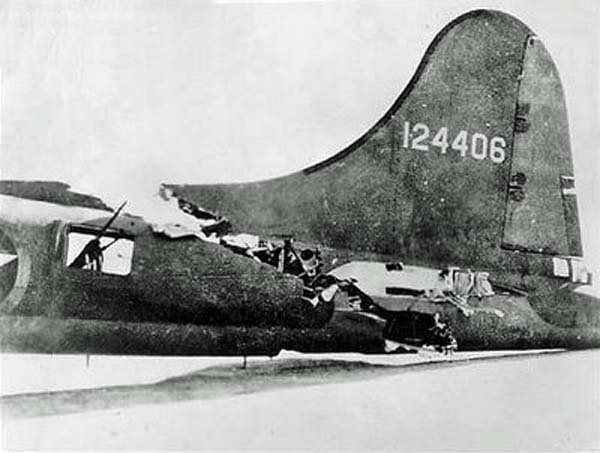

A mid-air collision on 1FEB1943 between a

B-17 and a German fighter over the Tunis dock area became the subject of

some of the most famous photographs of World War II.

An enemy fighter attacking a 97th Bomb Group formation

went out of control, probably with a wounded pilot, then continued its

crashing descent into the rear of the fuselage of a Fortress named All

American, piloted by Lt. Kendrick R. Bragg, of the 414th Bomb Squadron.

When it struck, the fighter broke apart, but left some pieces in the

B-17. The left horizontal stabilizer and elevator of the Fortress were

completely torn away.

The two right engines were out and one on the left had a serious oil

pump leak. The vertical fin and the rudder had been damaged, the

fuselage had been cut almost completely through – connected only at two

small parts of the frame and the radios, electrical and oxygen systems

were damaged. There was also a hole in the top that was over 16 feet

long and 4 feet wide at its widest and the split in the fuselage went

all the way to the top gunner’s turret. Although the tail actually

bounced and swayed in the wind and twisted when the plane turned and all

the control cables were severed , except one single elevator cable still

worked, and the aircraft still flew-miraculously!

The tail gunner was trapped because there was no floor connecting the

tail to the rest of the plane. The waist and tail gunners used parts of

the German fighter and their own parachute harnesses in an attempt to

keep the tail from ripping off and the two sides of the fuselage from

splitting apart. While the crew was trying to keep the bomber from

coming apart, the pilot continued on his bomb run and released his bombs

over the target.

When the bomb bay doors were opened, the wind turbulence was so great that

it blew one of the waist gunners into the broken tail section. It took

several minutes and four crew members to pass him ropes from parachutes

and haul him back into the forward part of the plane. When they tried

to do the same for the tail gunner, the tail began flapping so hard that

it began to break off. The weight of the gunner was adding some

stability to the tail section, so he went back to his position.

The turn back toward Biskra, Algeria, had to be very slow to

keep the tail from twisting off. They actually covered almost 70

miles to make the turn home. The bomber was so badly damaged that it

was losing altitude and speed and was soon alone in the sky.

For a brief time, two more Me109

German fighters attacked the All American. Despite the extensive

damage, all of the machine gunners were able to respond to these

attacks and soon drove off the fighters. The two waist gunners stood

up with their heads sticking out through the hole in the top of the

fuselage to aim and fire their machine guns. The tail gunner had to

shoot in short bursts because the recoil was actually causing the

plane to turn.

Allied P51 fighters intercepted the All American and took one of the pictures shown below. They also

radioed to the base describing the empennage was “waving like a fish

tail” and that the plane would not make it and to send out boats to

rescue the crew when they bailed out. The fighters stayed with the

Fortress taking hand signals from Lt. Bragg and relaying them to

the base. Lt. Bragg signalled that 5 parachutes and the spare had

been "used" so five of the crew could not bail out.

He made the decision that if they could not bail out safely, then he

would stay with the plane and land it. Two and a half hours after

being hit, the aircraft made its final turn to line up with the runway

while it was still over 40 miles away. It descended into an emergency

landing and a normal roll-out on its landing gear. When the ambulance

pulled alongside, it was waved off because not a single member of the

crew had been injured.

No one could believe that the aircraft could still fly in such a

condition. The Fortress sat placidly until the crew all exited through

the door in the fuselage and the tail gunner had climbed down a

ladder,

at which time the entire rear section of the aircraft collapsed onto

the ground.

The rugged old bird had done its job.

|

Stories often get either misleading with age, or become

expanded in the telling. The original version that I received a long while ago

gave the plane bombing Tunis and then returning to England!! As was pointed out

to me only recently it must have had one hell of a big fuel tank and a speed in

excess of Mach 2!! Hopefully the above version is now much nearer the truth. I

also was pointed in the direction of the pilots own version of events are told

by a relative of a member of the original crew. I wrote to a forum concerned and

asked for permission to use the item, they deigned not to reply so here it is:

The All American’s

Final Mission - The pilot of this

now-famous B-17 recalls her last flight

The All American (124406) was on a mission to Bizerta, Tunisia on February

1st 1943. It was classified as a routine mission against Rommel’s force – some

called it a “milk run”.

The enemy fighters attacked at 1350 on a clear almost cloudless day. The All

American was in tight formation with the other bombers, flying at 28,000 feet.

The enemy aircraft made their passes at the 17’s while anti aircraft fire

belched skyward.

The bombers located the target (the wharf area of Bizerta) and the bombardiers

dropped the bombs. With the bomb bays empty, the aircraft started home.

Kendrick R. Bragg, Jr. was the pilot of the All American and recalls what

happened after leaving Bizerta. “As we left the target and headed home, the

fast enemy ME-109’s once more rose to pounce on us. Suddenly I noticed two of

them far to the north sneaking along in the same direction that we were going.

They were out of range and harmless for the moment, but I told our gunners to

keep an eye on them. “We were flying Number 2 position off the right wind of

the lead plane piloted by Captain Coulter. He, too, had seen the two fighter

planes and I saw his top turret swing around toward the nose to protect the

plane’s most vulnerable quarter.

“I scanned the skies, then looked again at the two enemy craft. They had

suddenly turned and were racing toward us. The two small specks increased

rapidly in size as they came nearer. Evidently they were planning a frontal

attack, determined to shoot it out nose to nose. This was the most difficult

kind of attack but was the surest way of sending a Fortress down.

“On they came, one plane about thirty seconds behind the other. They were ready

for a one-two punch with their terrific firing power. We were flying in tight

formation now with Captain Coulter. He began a slight dive to avoid the

oncoming fighter, and I followed. They patterned us, managing to stay about

level with us. In a split second they were in shooting range and our forward

gunners opened fire. Brilliant tracer bullets flew in both directions, as

though a score of boys were fighting it out with Roman candles.

“The first attacker half-rolled into inverted flight to make a quick get-away.

As he did I saw Captain Coulter’s bomber burst into smoke and start earthward

in an uncontrolled spiral. The second enemy fighter was now our primary

concern. As she followed her leader into a roll our gunners found the mark.

Fifty-caliber bullets ripped into the pilot’s cockpit. The Nazi pilot was

disposed of, but the plane streaked on toward us. I rammed the stick forward in

a violent attempt to avoid collision. The rate of closure of the two planes was

close to 600 miles-an-jour and my action seemed sluggish. I flinched as the

fighter passed inches over my head and then I felt a slight thud like a coughing

engine.

“I checked the engines and the controls. The trim tabs were not working. I

tried to level the All American but she insisted on climbing. It was only with

the pressure from knees and hands that I was able to hold her in anything like a

straight line. The co-pilot tired his controls. He got the same reaction. But

we found by throttling back the engines we could keep her on a fairly even keel.

I tired to call the pilot of the lead plane which had gone down only a moment

before. There was no answer.

“Pilot from top-turret” came an excited voice over the intercom. I was busy

with the controls. “Come in top-turret. What’s the matter with you”? I asked.

“Sir we’ve received some damage in the tail section. I think you should have a

look.”

“We were at 12,000 feet now and no longer needed our oxygen masks. I turned the

controls over to the co-pilot and went toward the rear of the plane. As I opened

the door of the radio compartment and looked back into the fuselage I was

stunned. A torn mass of shredded metal greeted my eyes. Wires were dangling

and sheets of metal were flapping as the air rushed in through the torn

wreckage. Three-fourths of the plane had been cut completely through by the

enemy fighter and a large piece of the ME-109’s wing was lodged in the tail of

our plane.

“The opening made by the German fighter was larger than the exit door. It left

our tail section hanging on by a few slender spars an a narrow strip of metallic

skin. Lieutenant Bragg climbed into the upper turret to assess the damage from

the outside and discovered that the tail section was swinging as much as a foot

and a half out of line with the front of the plane. To make matters worse, the

left horizontal stabilizer was missing, explaining why the airplane was so

difficult to handle.

Bragg decided to try and make it back to Biskra. He returned to the seat,

ordered everyone to an emergency exit, then began the long journey home. He

recalls their arrival: “As we neared the field we fired three emergency flares,

then circled at 2,000 feet while the other planes cleared the runways. We could

see the alert crews, ambulances, and crash trucks making ready for us.

“Without radio contact with the field we had to wait for the signal that all was

clear and ready for us. When we got the signal I lowered the landing gear and

flaps to test the reaction of the All American. They seemed to go reasonably

well, considering. We had two alternatives. We could attempt a landing or we

could bail out over the field and let the plane fly alone until she crashed –

always a dangerous thing to do. I had made up my mind to set her down. She had

brought us safely through so far; I knew she would complete the mission. The

crew decided to ride her down too.

“A green flare from the field signaled that all was clear for our attempt at

landing. I made a long, careful approach to the strip with the partial power

until the front wheels touched the leveled earth. As I cut the throttles, I

eased the stick forward to hold the tail section high until it eased down of its

own weight as we lost speed. “The tail touched the earth and I could feel the grating as she dragged

without tail wheel along the desert sands. She came to a stop and I ordered the

co-pilot to cut the engines. We were home.”

My humble thanks to Robin Clay for bring this to my

attention. I appreciate it.

B-17's Bloody Nose

By Allen Ostrom

They could hear it before they could see it! Not all that unusual in those

days as the personnel at Station 131 gathered around the tower and

scattered hardstands to await the return of the B-17s sent out earlier

that morning.First

comes the far off rumble and drone of the Cyclones. Then a spec on

the East Anglia horizon. Soon a small cluster indicating the lead

squadron. Finally, the group.

Then the counting. 1-2-3-4-5. But

that would have been normal. Today was different! It was too early for the

group to return. "They're 20 minutes early. Can't be the 398th." They

could hear it before they could see it! Something was coming home. But

what?

All eyes turned toward the northeast, aligning with the main

runway, each ground guy and stood-down airman straining to make out this

"wail of a Banshee," as one called it. Not like a single B-17 with its

characteristic deep roar of the engines blended with four thrashing

propellers. This was a howl! Like a powerful wind blowing into a huge

whistle. Then it came into view. It WAS a B-17! Low and pointing her nose

at the 6,000 foot runway, it appeared for all the world to be crawling

toward the earth, screaming in protest. No need for the red flares. All

who saw this Fort knew there was death aboard.

"Look at that nose!"

they said as all eyes stared in amazement as this single, shattered

remnant of a once beautiful airplane glided in for an unrealistic "hot"

landing. She took all the runway as the "Banshee" noise finally abated,

and came to an inglorious stop in the mud just beyond the concrete runway.

Men and machines raced to the now silent and lonely aircraft. The

ambulance and medical staff were there first. The fire truck....ground and

air personnel... .jeeps, truck, bikes. Out came one of the crew members

from the waist door, then another. Strangely quiet. The scene was almost

weird. Men stood by as if in shock, not knowing whether to sing or cry.

Either would have been acceptable.

The medics quietly made their

way to the nose by way of the waist door as the remainder of the crew

began exiting.. And to answer the obvious question, "what happened?" "What

happened?" was easy to see. The nose was a scene of utter destruction. It

was as though some giant aerial can opener had peeled the nose like an

orange, relocating shreds of metal, Plexiglas, wires and tubes on the

cockpit windshield and even up to the top turret. The left cheek gun hung

limp, like a broken arm. One man pointed to the crease in chin turret. No

mistaking that mark! A German 88 anti-aircraft shell had exploded in the

lap of the togglier. This would be George Abbott of Mt. Lebanon, PA. He

had been a waist gunner before training to take over the bombardier's

role.

Still in the cockpit, physically and emotionally exhausted,

were pilot Larry deLancey and co-pilot Phil Stahlman. Navigator Ray

LeDoux finally tapped deLancey on the shoulder and suggested they get out.

Engineer turret gunner Ben Ruckel already had made his way to the waist

was exiting along with radio operator Wendell Reed, ball turret gunner Al

Albro, waist gunner Russell Lachman and tail gunner Herbert Guild.

Stahlman was flying his last scheduled mission as a replacement for

regular co-pilot, Grady Cumbie. The latter had been hospitalized the day

before with an ear problem.. Lachman was also a "sub," filling in for

Abbott in the waist.

DeLancey made it as far as the end of the

runway, where he sat down with knees drawn up, arms crossed and head down.

The ordeal was over, and now the drama was beginning a mental re-play.

Then a strange scene took place. Group CO Col. Frank P. Hunter had arrived

after viewing the landing from the tower and was about to approach

deLancey. He was physically restrained by flight surgeon Dr. Robert Sweet.

"Colonel, that young man doesn't want to talk now. When he is ready you

can talk to him, but for now leave him alone." Sweet handed pills out to

each crew member and told them to go to their huts and sleep. No

dramatics, no cameras, no interviews. The crew would depart the next day

for "flak leave" to shake off the stress. And then be expected back early

in November. (Just in time to resume "normal" activities on a mission to

Merseburg!)

Mission No. 98 from North Hampstead had begun at 0400

that morning of October 15, 1944. It would be Cologne (again), led by CA

pilots Robert Templeman of the 602nd, Frank Schofield of the 601st and

Charles Khourie of the 603rd. Tragedy and death appeared quickly and early

that day. Templeman and pilot Bill Scott got the 602nd off at the

scheduled 0630 hour, but at approximately 0645 Khouri and pilot Bill

Meyran and their entire crew crashed on takeoff in the town of Anstey .

All were killed. Schofield and Harold Stallcup followed successfully with

the 601st, with deLancey flying on their left wing in the lead element.

The ride to the target was routine, until the flak started becoming

"unroutinely" accurate.

"We were going through heavy flak on the

bomb run," remembered deLancey. "I felt the plane begin to lift as the

bombs were dropped, then all of a sudden we were rocked by a violent

explosion. My first thought - 'a bomb exploded in the bomb bay' - was

immediately discarded as the top of the nose section peeled back over the

cockpit blocking the forward view." It seemed like the whole world

exploded in front of us," added Stahlman. "The instrument panel all but

disintegrated and layers of quilted batting exploded in a million pieces.

It was like a momentary snowstorm in the cockpit."

It had been a

direct hit in the nose. Killed instantly was the togglier, Abbott.

Navigator LeDoux, only three feet behind Abbott, was knocked unconscious

for a moment, but was miraculously was alive. Although stunned and

bleeding, LeDoux made his way to the cockpit to find the two pilots

struggling to maintain control of an airplane that by all rights should

have been in its death plunge. LeDoux said there was nothing anyone could

do for Abbott, while Ruckel opened the door to the bomb bay and signaled

to the four crewman in the radio room that all was OK - for the time

being. The blast had torn away the top and much of the sides of the nose.

Depositing enough of the metal on the windshield to make it difficult for

either of the pilots to see. "The instrument panel was torn loose and all

the flight instruments were inoperative with the exception of the magnetic

compass mounted in the panel above the windshield And its accuracy was

questionable. The radio and intercom were gone, the oxygen lines broken,

and there was a ruptured hydraulic line under my rudder pedals," said

deLancey.

All this complicated by the sub-zero temperature at

27,000 feet blasting into the cockpit. "It was apparent that the damage

was severe enough that we could not continue to fly in formation or at

high altitude. My first concern was to avoid the other aircraft in the

formation, and to get clear of the other planes in case we had to bail

out. We eased out of formation, and at the same time removed our oxygen

masks as they were collapsing on our faces as the tanks were empty." At

this point the formation continued on its prescribed course for home - a

long, slow turn southeast of Cologne and finally westward.

DeLancey

and Stahlman turned left, descending rapidly and hoping, they were heading

west.. (And also, not into the gun sights of German fighters.) Without

maps and navigation aids, they had difficulty getting a fix. By this time

they were down to 2,000 feet. "We finally agreed that we were

over Belgium and were flying in a southwesterly direction," said the

pilot.

"About this time a pair of P-51s showed up and

flew a loose formation on us across Belgium .

I often wondered what they thought as they looked at the mess up front."

We hit the coast right along the Belgium-Holland border, a bit farther

north than we had estimated Ray said we were just south of Walcheren

Island ."

Still in an area of ground fighting, the plane received

some small arms fire. This gesture was returned in kind by Albro, shooting

from one of the waist guns. "We might have tried for one of the airfields

in France ,

but having no maps this also was questionable. Besides, the controls and

engines seemed to be OK, so I made the decision to try for home." Once

over England ,

LeDoux soon picked up landmarks and gave me course corrections taking us

directly to North Hampstead. It

was just a great bit of navigation. Ray just stood there on the flight

deck and gave us the headings from memory."

Nearing the field,

Stahlman let the landing gear down. That was an assurance. But a check of

the hydraulic pump sent another spray of oil to the cockpit floor.

Probably no brakes! Nevertheless, a flare from Ruckel's pistol had to

announce the "ready or not" landing. No "downwind leg" and "final

approach" this time. Straight in! "The landing was strictly by guess and

feel," said DeLancey. "Without instruments, I suspect I came in a little

hot. Also, I had to lean to the left to see straight ahead. The landing

was satisfactory, and I had sufficient braking to slow the plane down

some. However, as I neared the taxiway, I could feel the brakes getting

'soft'. I felt that losing control and blocking the taxiway would cause

more problems than leaving the plane at the end of the runway." That

consideration was for the rest of the group. Soon three squadrons of B-17s

would be returning, and they didn't need a derelict airplane blocking the

way to their respective hardstands.

Stahlman, supremely thankful

that his career with the 398th had come to an end, soon returned home and

in due course became a captain with Eastern Airlines. Retired in 1984,

Stahlman said his final Eastern flight "was a bit more routine" than the

one 40 years before. DeLancey and LeDoux received decorations on December

11, 1944 for their parts in the October 15 drama. DeLancey was awarded the

Silver Star for his "miraculous feat of flying skill and ability" on

behalf of General Doolittle , CO of the Eighth Air Force. LeDoux for his

"extraordinary navigation skill", received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The following DeLancey 1944 article was transcribed from the 398th

BG Historical Microfilm. Note: due to wartime security, Northampstead is

not mentioned, and the route DeLancey flew home is referred to in general

terms.

TO: STARS AND STRIPES FOR GENERAL RELEASE

AN EIGHTH

AIR FORCE BOMBER STATION, ENGLAND - After literally losing the nose of his

B-17 Flying Fortress as the result of a direct hit by flak

over Cologne, Germany, on October 15, 1944, 1st Lt. Lawrence M. DeLancey,

25, of Corvallis, Oregon, returned to England and landed the crew safely

at his home base. Each man walked away from the plane except the togglier,

Staff Sergeant George E. Abbott, Mt.

Lebanon, Pennsylvania, who was

killed instantly when the flak struck. It was only the combined skill and

teamwork of Lt. DeLancey and 2nd Lt. Raymond J. LeDoux, of Mt.

Angel, Oregon, navigator, that

enabled the plane and crew to return safely.

"Just after we dropped

our bombs and started to turn away from the target," Lt. DeLancey

explained, "a flak burst hit directly in the nose and blew practically the

entire nose section to threads. Part of the nose peeled back and

obstructed my vision and that of my co-pilot, 1st Lt. Phillip H. Stahlman

of Shippenville, Pennsylvania.

What little there was left in front of me looked like a scrap heap. The

wind was rushing through. Our feet were exposed to the open air at nearly

30,000 feet above the ground the temperature was unbearable.

"There

we were in a heavily defended flak area with no nose, and practically no

instruments. The instrument panel was bent toward me as the result of the

impact. My altimeter and magnetic compass were about the only instruments

still operating and I couldn't depend on their accuracy too well.

Naturally I headed for home immediately. The hit which had killed S/Sgt.

Abbott also knocked Lt. LeDoux back in the catwalk (just below where I was

sitting). Our oxygen system also was out so I descended to a safe

altitude.

"Lt. LeDoux who had lost all his instruments and maps in

the nose did a superb piece of navigating to even find England ..."

During the route home flak again was encountered but due to evasive

action Lt. DeLancey was able to return to friendly territory. Lt.. LeDoux

navigated the ship directly to his home field.

Although the plane

was off balance without any nose section, without any brakes (there was no

hydraulic pressure left), and with obstructed vision, Lt. deLancey made a

beautiful landing to the complete amazement of all personnel at this field

who still are wondering how the feat was accomplished.

The other

members of the crew include:

1. Technical Sergeant

Benjamin H. Ruckel, Roscoe, California, engineer top turret gunner;

2. Technical Sergeant Wendell A. Reed, Shelby, Michigan, radio operator

gunner;

3. Technical Sergeant Russell A. Lachman,

Rockport, Mass., waist gunner;

4. Staff Sergeant Albert

Albro, Antioc h, California, ball turret gunner

5. Staff Sergeant

Herbert D. Guild, Bronx, New York, tail gunner.

Piggy Back Ride

In 2003 they

laid the remains of Glenn Rojohn to rest in the Peace Lutheran Cemetery in

the little town of Greenock, Pa., just southeast of Pittsburgh. He was 81,

and had been in the air conditioning and plumbing business in nearby

McKeesport. If you had seen him on the street he would probably have

looked to you like so many other graying, bespectacled old World War II

veterans whose names appear so often now on obituary pages.

But

like so many of them, though he seldom talked about it, he could have told

you one hell of a story. He won the Air Medal, the Distinguished Flying

Cross and the Purple Heart all in one fell swoop in the skies over Germany

on December 31, 1944. Fell swoop indeed.

Capt.

Glenn Rojohn, of the 8th Air Force's 100th Bomb Group was flying his B-17G

Flying Fortress bomber on a raid over Hamburg. His formation had braved

heavy flak to drop their bombs, then turned 180 degrees to head out over

the North Sea. They had finally turned northwest, headed back to England,

when they were jumped by German fighters at 22,000 feet. The Messerschmitt

Me-109s pressed their attack so closely that Capt. Rojohn could see the

faces of the German pilots. He and other pilots fought to remain in

formation so they could use each other's guns to defend the group. Rojohn

saw a B-17 ahead of him burst into flames and slide sickeningly toward the

earth. He gunned his ship forward to fill in the gap. He felt a huge

impact. The big bomber shuddered, felt suddenly very heavy and began

losing altitude. Rojohn grasped almost immediately that he had collided

with another plane. A B-17 below him, piloted by Lt. William G. McNab, had

slammed the top of its fuselage into the bottom of Rojohns. The top

turret gun of McNabs plane was now locked in the belly of Rojohns plane

and the ball turret in the belly of Rojohns had smashed through the top of

McNabs. The two bombers were almost perfectly aligned at the tail of the

lower plane was slightly to the left of Rojohns tailpiece. They were stuck

together, as a crewman later recalled, like mating dragon flies.

Three of the engines on the bottom plane were still running, as were all

four of Rojohns. The fourth engine on the lower bomber was on fire and the

flames were spreding to the rest of the aircraft. The two were losing

altitude quickly. Rojohn tried several times to gun his engines and break

free of the other plane. The two were inextricably locked together.

Fearing a fire, Rojohn cut his engines and rang the bailout bell. For his

crew to have any chance of parachuting, he had to keep the plane under

control somehow.

The

ball turret, hanging below the belly of the B-17, was considered by many

to be a death trap the worst station on the bomber. In this case, both

ball turrets figured in a swift and terrible drama of life and death.

Staff Sgt. Edward L. Woodall, Jr., in the ball turret of the lower bomber

had felt the impact of the collision above him and saw shards of metal

drop past him. Worse, he realized both electrical and hydraulic power was

gone.

Remembering escape drills, he grabbed the handcrank, released

the clutch and cranked the turret and its guns until they were straight

down, then turned and climbed out the back of the turret up ino the

fuselage. Once inside the planes belly Woodall saw a chilling sight, the

ball turret of the other bomber protruding through the top of the

fuselage. In that turret, hopelessly trapped, was Staff Sgt. Joseph Russo.

Several crew members of Rojohns plane tried frantically to crank Russos

turret around so he could escape, but, jammed into the fuselage of the

lower plane, it would not budge. Perhaps unaware that his voice was going

out over the intercom of his plane, Sgt. Russo began reciting his Hail

Marys.

Up in the cockpit, Capt. Rojohn and his co-pilot 2nd Lt.

William G. Leek, Jr., had propped their feet against the instrument panel

so they could pull back on their controls with all their strength, trying

to prevent their plane from going into a spinning dive that would prevent

the crew from jumping out. Capt. Rojohn motioned left and the two managed

to wheel the huge, collision-born hybrid of a plane back toward the German

coast. Leek felt like he was intruding on Sgt. Russo as his prayers

crackled over the radio, so he pulled off his flying helmet with its

earphones.

Rojohn,

immediately grasping that crew could not exit from the bottom of his

plane, ordered his top turret gunner and his radio operator, Tech Sgts.

Orville Elkin and Edward G. Neuhaus to make their way to the back of the

fuselage and out the waist door on the left behind the wing. Then he got

his navigator, 2nd Lt. Robert Washington, and his bombardier, Sgt. James

Shirley to follow them. As Rojohn and Leek somehow held the plane steady,

these four men, as well as waist gunner, Sgt. Roy Little, and tail gunner,

Staff Sgt. Francis Chase, were able to bail out.

Now the plane

locked below them was aflame. Fire poured over Rojohns left wing. He could

feel the heat from the plane below and hear the sound of .50 machinegun

ammunition cooking off in the flames. Capt. Rojohn ordered Lieut. Leek to

bail out. Leek knew that without him helping keep the controls back, the

plane would drop in a flaming spiral and the centrifugal force would

prevent Rojohn from bailing out. He refused the order.

Meanwhile,

German soldiers and civilians on the ground that afternoon looked up in

wonder. Some of them thought they were seeing a new Allied secret weapon a

strange eight-engined double bomber. But anti-aircraft gunners on the

North Sea coastal island of Wangeroge had seen the collision. A German

battery captain wrote in his logbook at 12:47 p.m.:

Two

fortresses collided in a formation in the NE. The planes flew hooked

together and flew 20 miles south. The two planes were unable to fight

anymore. The crash could be awaited so I stopped the firing at these two

planes.

Suspended in his parachute in the cold December sky,

Bob Washington watched with deadly fascination as the mated bombers,

trailing black smoke, fell to earth about three miles away, their downward

trip ending in an ugly boiling blossom of fire.

In the cockpit

Rojohn and Leek held grimly to the controls trying to ride a falling rock.

Leek tersely recalled, The ground came up faster and faster. Praying was

allowed. We gave it one last effort and slammed into the ground. The McNab

plane on the bottom exploded, vaulting the other B-17 upward and forward.

It slammed back to the ground, sliding along until its left wing slammed

through a wooden building and the smoldering mess came to a stop. Rojohn

and Leek were still seated in their cockpit. The nose of the plane was

relatively intact, but everything from the B-17 massive wings back was

destroyed. They looked at each other incredulously. Neither was badly

injured.

Movies have nothing on reality. Still perhaps in shock,

Leek crawled out through a huge hole behind the cockpit, felt for the

familiar pack in his uniform pocket pulled out a cigarette. He placed it

in his mouth and was about to light it. Then he noticed a young German

soldier pointing a rifle at him. The soldier looked scared and annoyed. He

grabbed the cigarette out of Leaks mouth and pointed down to the gasoline

pouring out over the wing from a ruptured fuel tank.

Two of the six

men who parachuted from Rojohns plane did not survive the jump. But the

other four and, amazingly, four men from the other bomber, including ball

turret gunner Woodall, survived. All were taken prisoner. Several of them

were interrogated at length by the Germans until they were satisfied that

what had crashed was not a new American secret weapon.

Rojohn,

typically, didn't talk much about his Distinguished Flying Cross. Of Leek,

he said, in all fairness to my co-pilot, he's the reason I'm alive today.

Like so many veterans, Rojohn got unsentimentally back to life after

the war, marrying and raising a son and daughter. For many years, though,

he tried to link back up with Leek, going through government records to

try to track him down. It took him 40 years, but in 1986, he found the

number of Leeks mother, in Washington State. Yes, her son Bill was

visiting from California. Would Rojohn like to speak with him? Some things

are better left unsaid. One can imagine that first conversation between

the two men who had shared that wild ride in the cockpit of a B-17. A year

later, the two were re-united at a reunion of the 100th Bomb Group in Long

Beach, Calif. Bill Leek died the following year.

Glenn Rojohn was

the last survivor of the remarkable piggyback flight. He was like

thousands upon thousands of men, soda jerks and lumberjacks, teachers and

dentists, students and lawyers and service station attendants and store

clerks and farm boys who in the prime of their lives went to war.

The Airman Who Wouldn't Give Up |

![]()