This Secret Place

War Cabinet Rooms

http://www.iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms

The Cabinet War Rooms lie buried under the

curlicued pile of a government building in Horse Guards Road off

Whitehall . More than 150 cell-like rooms, some no larger than a fox’s

den, open off a mile of corridors. They cover more than an acre, mostly

beneath two-foot steel beams and a four-foot-thick slab of solid

concrete. At the height of the war as many as 300 people worked in these

cellars. To them it was “The Hole,” or simply “down there. ” But to

Winston Churchill it was “This Secret Place. ”

In these rooms in May 1940 Churchill

declared, “ If invasion comes this is where I shall sit. " Pointing to

his chair at the head of the Cabinet table, he said: “I shall sit there

until either the Germans are driven back, or they carry me out dead.”

In this vast subterranean headquarters

every stratagem in the death-duel with Germany was debated, each stroke

of war recorded. Here giant maps and charts, studded with coloured pins,

marked the great land, sea and air battles. Here the magnificent hoaxes

of “The Man Who Never Was” and “Monty’s Double” were cooked up. Here,

from his bed-sitter, Churchill made four of his historic broadcasts, and

from a room no larger than a lavatory held his telephone conversations

with President Roosevelt in Washington. After the war the bulk of the

space was converted into storerooms or abandoned to reverberating

emptiness. But six of the rooms were preserved as a memorial, and now another dozen,

meticulously restored, have been opened to the public.* On the wall

of the Prime Minister’s bedroom, no longer concealed by the curtain

which was its only wartime protection, hangs the most secret map which

showed in detail every preparation against invasion.

In the official Map Room, score was kept during the Battle of Britain of

downed enemy and British aircraft, on a device like a Test Match

scoreboard The estimated score of the big day of the match, September

15, 1940, still stands on the board: Germany, downed 183, probable 42,

damaged 75. Near by is the Cabinet Room where, in the blackest days of

the war, one of the most crucial meetings of the Cabinet was called.

Churchill, who was in Cairo, had sent a request for a new commander in

North Africa, where Rommel was piling up victory after victory. But the

officer he asked for had already been appointed to General Eisenhower’s

staff in London. The Cabinet debated the issue through the night until

Ernest Bevin, the lights glinting on his pebble spectacles, the stub of

a cigarette stuck to his lower lip, said, “We either have to send the

man or propose an altemate. Since we don’t have an alternate, we’ll have

to send the man Winston wants. ”The man, of course, was Montgomery, and

his triumph over Rommel at El Alamein turned the tide in the war. For

comic relief, it was also in “The Hole” in the summer of 1940 that a

young officer came up with a surefire method of stopping Operation Sea

Lion, Hitler’ s projected invasion of England.

The German plan

was first for the Luftwaffe to beat down the RAF. Next, in combination

with the German navy, it would knock out the Home Fleet. Hundreds of

barges laden with Nazi soldiers were then to be towed and pushed across

the English Channel. Once ashore, to eliminate the need to transport

petrol, the troops would mount bicycles for the final advance. The junior

officer spoke up: “When they get ashore,” he asked, “couldn’t we just let

the air out of their tyres?”

If ’Itler Could ’Ear ’Im”

“THE HOLE” was first

manned during the Munich Crisis; Chamberlain visited it on the day war

was declared. But it was under Churchill that it assumed the air of

urgency and excitement which a visitor can still feel today. “People

call it Hitler’s war,” says one officer who served in This Secret Place.

“It wasn’t. Hitler may have started it, but after the tenth of May 1940,

when he took over, it was Winston‘s war. He fought it with all the gusto

of a fourth form schoolboy surrounded by his chums, putting paid

to a bully. Of course they called this place the Cabinet War Rooms, but

it was really Stalky and Co.’s cave, and Winston was Stalky.”

Characteristically, soon after, assuming his post as Prime Minister,

Churchill made an inspection of his fortress. He arrived without warning

swept through the rooms, then asked for the exit that led most directly

to No. 10 Downing Street. Guided to a little-used door, he stepped from

the gloom into an English May moming; as if drawn by some invisible

force a small knot of workmen materialized, and when Churchill moved

through them, his stick pounding an obligato to his firmly planted feet,

they burst into an impromptu cheer. Smiling, but his eyes moist, he told

a companion, “They trust me, and I can give them nothing but disaster

for quite a long time. ”

The heart of “The Hole” consisted of the

two main rooms: the official Map Room, and the Cabinet Room. The latter

is today, as it was then, a simple rectangular space filled with a series

of tables set in the form of a hollow square. Crowded round the tables

are the Ministers’ chairs and at the centre of the table to the left of

the door is a wooden Windsor armchair. This was Churchill’s. It was the

decisions taken here which in the end were reflected in the victories and

defeats shown on the walls of the Map Room.

When a Cabinet

meeting was called here, Churchill entered first, and the others followed

and took their places among them Minister of Labour Ernest Bevin and the

gnome-like Lord Beaverbrook. Flaming-haired Brendan Bracken, Churchill’s

Parliamentary Private Secretary and later Minister of Information, would

occasionally be called in to join them, as would “The Prof”, Professor

F. E. Lindemann, later Lord Cherwell. Always on Churchill’s immediate

left was the Deputy Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, a quiet man with an

inscrutable face, yet capable of moments of anger. These could be

induced by any slight that he, an old infantry officer, felt was being

placed on the Army. After calling the meeting to order Churchill would

bring up the first item on the agenda. The Minister whose department was

concerned spoke and was then challenged. As argument began, voices rose.

Churchill, revelling in the rough and tumble of debate, joined in until

his voice, lustily intoning parliamentary phrases, drowned out his

colleagues. Although the room was soundproofed, a small grille covered

by wire netting had been left open. lf there was a large difference of

opinion the sound-level climbed until it overflowed through the grille.

During one roaring interval, a Royal Marine on duty remarked: “If ’Itler

could ’ear ’im, ’e’d belt up and run. ”

During these gales, the

secretaries took down the Cabinet decisions in longhand, and at the

close of the meeting dashed off to dictate the results to typists. The

reports were then rushed off for duplicating. Since Churchill was a man

who was at his best after 5pm, he often called his Cabinet meetings late

at night. It was a point of pride that, throughout the entire war, no

matter at what hour the typists got the reports, a copy of the

proceedings of the previous night was on each Minister’s breakfast table

by morning. In the Cabinet Room, Churchill, who in addition to being

Prime Minister had named himself as Minister of Defence, conferred also

with the Chiefs of Staff. Although there were only the three chiefs, Gen

Alanbrooke for the Army, Sir Dudley Pound for the Royal Navy and Sir

Charles Portal for the RAF, and the secretariat, these sessions greatly

resembled the Cabinet meetings in point of decibels, finnness of purpose

and debate. Air Chief Marshal Portal used to state his views succinctly

and quietly, but General Alanbrooke, a slight man with long arms, had a

rush of speech in which words tumbled over each other, like a river in

spate, and sometimes managed to get mixed up in the process . Once he

spent half an hour detailing a military position near Iran, which he

kept referring to as Germany. When an aide tried to prompt him, General

Brooke snapped: “Don’t correct me, you know damn well what I mean!”

Admiral Pound on the other hand always appeared to be dozing until the

word “Navy” was mentioned, but then he came awake with a rush, firing

broadsides of argument and opinion.

Meanwhile, Churchill, who had

his own views on military matters, sat in his chair like a swordsman

facing the Three Musketeers single-handed, laying about him in all

directions at once. An American observer, unused to the ancient British

custom of loud and simultaneous debate, left one such session with his

head reeling. “ It was like the Tea Party in Alice in Wonderland,” he

said, “except that the Mad Hatter kept on tuming into the March Hare! ”

The Nerve Centre

In contrast to the Cabinet Room, the Map Room carried on its work in

comparative silence. The atmosphere was, however, charged with tension,

particularly during the great naval engagements, the Graf Spee, the

Bismarck, the hunting of the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau. Then, as the

positions of ships and planes were changed, almost as the action

transpired, the room filled up and everyone seemed to hold his breath.

“You could almost hear the flash of the guns and the blast of the

torpedoes,” says a civil servant who was there. “After the Bismarck was

sunk, I went outside and it wasn’t until I started to cross Whitehall

that I realized my legs were trembling so that I was scarcely able to

walk. ” Like the other underground rooms, the Map Room’s roof is propped

up with giant baulks of timber to support the vast weight of the

building. These pillars add to the illusion that the room is a battle

headquarters deep in the vitals of a warship. Down the centre of the

room are two long tables, still littered with yellowing papers detailing

events of 40 years ago. On top of each table is a raised shelf filled

with red, white and green telephones, equipped with flashing lights

instead of bells, and scrambling devices. These were used by watch

officers of the three Services, none below the rank of lieutenant colonel

or its equivalent, who sat there receiving direct reports from their

headquarters, by telephone and by compressed-air tubes, and passing the

information on to the officers manning the gigantic wall maps. Facing the

two tables is a desk, once occupied by a colonel who correlated the

reports from each Service. Still on the desk are two leather-covered

dispatch boxes, each bearing a crown. One is dirty black and labelled

“The Cabinet and Committee of Imperial Defence.” The other, faded red,

is labelled “The King. ” These were delivered daily to Buckingham Palace

and to the Prime Minister’s office.

From September 1939, when the Polish and German armies, translated

into rows of red and blacktopped pins stuck into maps, faced each other,

the Map Room was always the eye of the hurricane. As word of the gallant

but hopeless surge of Polish lancers against German tanks and

self-propelled cannon reached the room, the red-topped pins representing

Polish units were moved forward towards the black-topped pins of the

Germans. Then, as the Polish Anny collapsed, the red-topped pins were

swept off the maps and dropped into a box.

These were Germany’s

days of glory, the days when the black-topped pins everywhere moved

forward invincibly. Five years later, these same pins were dropped one

by one into another box signalling defeat, absolute and utter, on all

fronts, in the air, at sea and in the rubble of its ancient cities.

Churchill, who was a man best able to appreciate a situation when it was

visualized, lived with maps. After taking over as Prime Minister he had

his own personal map room moved from the Admiralty to a site adjoining

his own living quarters. Although the information furnished to both

rooms was identical, Churchill, who hated the fluorescent tubes over the

maps, preferred to look at his own versions. Often when he was in “The

Hole” and needed to pin-point a position, he would pore over a schoolboy

atlas which he kept in his desk drawer.

King George VI, who was a

frequent visitor to the fortress, had no reservations about the

fluorescent lighting. He liked to check not only the maps but the

statistical charts with which the walls were covered. One wall of the

Map Room still carries the great sea map of the world on which fleet

positions, enemy U-boats and the daily progress of convoys were charted.

Here a closely guarded secret, the whereabouts of the Queen Mary and the

Queen Elizabeth, each bearing 15,000 men, were marked by special

flag-topped pins.

This map, conventionally lit, was Churchill’s

favourite and any time he entered the Map Room he made a beeline for it.

Fascinated by the movements of convoys, the lifeline of the country, he

frequently asked probing questions of the men on watch as to why certain

ships were not moving as rapidly as they might or why they were holed up

in port. On one particular occasion a ship caught his fancy; he leamed

that it was lumbering slowly through the U-boat-infested North Atlantic

carrying a cargo of 6,000 tons of eggs. Daily he noted its progress,

seeming to feel every pitch and roll of its passage. Finally he turned

to his crony, F. E. Lindemann, the bowler-hatted Oxford don, regarded by

Churchill as a sort of portable thinking machine, and asked him how many

actual eggs 6,000 tons represented. The Prof switched on the full

voltage of his brainpower, considered the matter, and delivered an

answer: 107 million. The Churchillian figure seemed to swell. “That

means,” he thundered, “two eggs for every man, woman and child in

Britain!” Having solved this, the two men were able to refocus on

winning the war.

While the great egg question may have seemed trivial, it was one more

proof to the Prime Minister of The Prof’s giant mental resources. During

the Battle of Britain and later on the road back to El Alamein, The

Prof’s self-confidence and Churchill’s confidence in his intellect were to

have a signal effect in turning Britain’s effort from defensive to

offensive action. At that time, impressed by Germany’ s overwhelming air

superiority, the military were adamant about keeping more planes in

reserve than Churchill felt were necessary. Turning to The Prof for

help, the Prime Minister received the answer that the military were

wrong. The Prof had been studying the figures on the Map Room wall which

showed the daily rate of air casualties on both sides, and had come to

the conclusion, by complicated reasoning, that there were far fewer

German planes than anyone had imagined. Armed with this calculation from

a source he considered infallible, Churchill fought the military to a

standstill and got the squadrons he wanted for his counter attacking

strategy.

After the war was over, it appeared from captured

German records that The Prof had been off beam: the military were indeed

right in their estimates. But in the meantime Churchill had gained his

point, got his planes and prepared for the crucial battle of El Alamein.

Hot Line to Washington

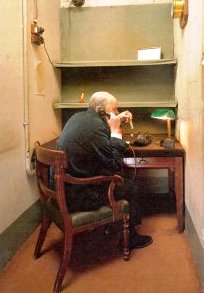

While the Map Room and the Cabinet Room were the heart of the operation,

a small lavatory-sized room, which even has a lavatory-lock, was also a

key position. Here was the scrambler telephone over which Churchill

carried on his wartime conversations with President Roosevelt in the

White House. The telephone was installed by the US Signal Corps, and the

instructions for its use, “Speak in a normal voice,” are still in

position on the small shelf holding the telephone. The conversations

were carried on in strictest secrecy and, when the lock on the door

read, “Engaged,” the corridors were cleared so that no details of the

transatlantic conversations could be overheard. In the room is a clock

with London time indicated by black hands and Washington time by red.

Despite this, Churchill was not a man to be influenced by the hour if he

had something on his mind. His calls were as likely to reach Washington

at 3am as at a more civilized hour. Whenever a call was made, a small

comedy of manners took place. Neither Churchill nor Roosevelt relished

holding the telephone until the other was there and ready to speak.

Consequently, once the call had been placed, Major General Hollis or a

secretary held the line until he was sure the US President was actually

on the telephone. In Washington the same procedure was followed, and the

ploy of ensuring that both men came on the line at the same time had

secretarial nerves snapping like banjo strings. When Churchill finally

got to the telephone, he was never without a fresh cigar which he smoked

throughout the conversation. The room was small and, although the edges

of the door were nearly flush with the jamb, there were leaks through

which the smoke would come curling into the corridor like wisps of

smouldering brimstone from some entry to Hell. Then, the conversation at

an end, Churchill, clad usually in his dragon-covered dressing-gown,

would throw open the door and stride forth. Describing it, one of his

aides says, “When Winston opened the door, the suddenblaze of light in

the dark corridor, the rush of pent-up smoke, and Winston in his dragons

. . . it all looked as though Lucifer had made a sudden ascent to earth

and was looking for a victim-—you ! ”

The Disappearing Chairs

“The Hole” came into being with a casualness as deceptive as the

organization of a game of darts in a village pub. In 1938 the Committee

of Imperial Defence, following a memorandum from its deputy secretary,

Colonel Hastings (“Pug”) Ismay, concluded that if Germany declared war

on Britain, she might attack by bombing. This meant that a place must be

prepared for the Cabinet and Chiefs of Staff to meet safe from bombs.

The Treasury provided £500 to start the project; and two men, Leslie

Hollis, then a Major in the Royal Marines, and Lawrence Burgis, a civil

servant from the Cabinet secretariat, were assigned to find the site.

Hollis and Burgis, after surveying the situation, decided that the best

possible site would be the cellars of the building shared by the Office

of Works (now absorbed into the Department of the Environment) and the

Board of Education in Horse Guards Road, within easy walking distance of

No. 10 Downing Street, the Foreign Office, Buckingham Palace and

Parliament. Erected in the reign of Edward VII, the building looked

solid enough to shed bombs without further strengthening. In addition,

the Office of Works, who would have to be let in on the secret of the

construction, had an office just over the cellars. A senior official of

the Office, Eric de Normann, was taken into the confidence of Burgis and

Hollis, and work got under way. A fourth member was added to the team

with the introduction of George Rance, an ex Sergeant in the Rifle

Brigade, in charge of the pay sheets of the charwomen in the Office of

Works. Rance proved to be a man of vast talent and enterprise.

He

was asked to clear out the old cellars and, without arousing any

suspicion, fit them out with tables, chairs. lights, camp-beds and a few

supplies. An old soldier who knew how to scrounge, he did the work with

exemplary secrecy. One of his regular jobs was ordering furniture for

the Office of Works . Now, when he was given a legitimate order for one

chair he added an unauthorized order for another one, and stored the

second in the cellars. He did the same with table lamps and other

equipment. As time went on, he was in effect whisking van-loads of

fumiture to the cellars with the speed and the practised stealth of a

Merlin. To keep outsiders from nosing round and asking questions,

special locks were fitted to the doors, and Rance held the only keys.

Meanwhile, maps and documents from the Admiralty, the War Office and

the Foreign Office were smuggled in as well, addressed simply “c/o Mr

Rance, Office of Works, Whitehall.” This became, in time, a code word for

the entire operation; acts of the highest secrecy by people of the Very

Highest Rank were carried out in Rance’s name. Other secret work went on

under the guidance of Hollis and Burgis. The original £500 had been only

enough to buy wooden beams to shore up the ceilings, but now with the

help of Warren Fisher, Secretary to the Treasury, money was forthcoming

to provide steel doors and air locks for barriers in case of gas attack.

Soon the ceilings were festooned with the ganglia of naked electrical

wiring, left exposed so that repairs could be made easily, and piping

for air-conditioning. To make sure that no one realized what was going

on in the cellars, the air-ducts were carried to another building half a

mile away.

The entire operation of creating This Secret Place was

tantamount to spiriting away an elephant through a crowd without anyone

noticing. However, the team brought it off; throughout the war few

people had any idea where the command post was. The Least Safe Place

WHAT had started out to be a simple bombproof bunker had now grown into

a fortress which soon required an independent water supply. Following

high-level scientific discussion, a water diviner with the reputation of

being able to locate a raindrop under a block of concrete was brought

in. After a day of wandering round the cellars, he pointed dramatically

and said, “Dig here. ” They dug and—Eureka!—a cascade.

This

Secret Place was also equipped with specially armoured cables to supply

electricity and with its own emergency generating plant. These double

measures were essential, not only to keep the lights buming but to run

the pumps, for the lower cellars, being at the water-level of the

Thames, were in danger of flooding should a bomb score a hit. Initially,

feeding arrangements in This Secret Place merely consisted of a

primitive portable stove used by the Royal Marine guards to brew up tea.

Later, after working all night it was possible to get eggs and bacon at

the same source. More and more people began to rely on getting their

breakfast in the cellars until finally a full-scale canteen was

installed, and a dining-room for the General Staff.

The major

defence for the fortress was the four-foot-thick slab of concrete filling

the space once occupied by a suite of offices just below the ground floor

but above the topmost level of the cellars. Work on this went on through

the Blitz, much to the annoyance of Churchill. When the sounds of

workmen filtered down even into the Cabinet Room, he would halt all

business and, banging his hand on the table in time to his prose, roar

at one of the secretaries, “Can you not stop that damned knock, knock,

KNOCKING?”

After one of these outbursts the noise would stop, but

in time it led to a sort of game between the workmen and Churchill.

Daily, word was passed via Rance as to Churchill’s whereabouts. If he

was in the building, not a workman stirred; if he was not, work went on

at top speed. But Churchill’s movements were unpredictable, and the men

took to doing their job with one eye on a look-out who warned them when

to bang and when to retire for a cup of tea. Despite the interruptions,

the slab, reinforced with a criss-cross of old tram lines, was finally

finished and calculated to be solid enough to withstand the force of a

500-pound bomb. To give further protection, wire netting was woven round

the airshafts and stair well. One night during the Blitz when a

1,000-pounder fell within 50 yards, Churchill grumbled because it wasn’t

closer. “Help us to test our defences , ” he growled.

It was perhaps fortunate he never got his wish, for “The Hole’s”

resistance to damage was more theoretical than practical. After the war,

Lawrence Burgis said, “We didn’t know how unsafe we really were. True, a

direct hit wouldn’t have caused us any harm, but if a bomb had come in

at an angle it would have demolished us. The engineers told us later

that under air attack, the fortress was one of the least safe places in

London.”

That Famous “V”

When a near miss from a

German bomb demolished part of No. 10 Downing Street, Churchill and his

family moved to the flat, known as the Annexe, prepared for them in a

suite of offices immediately over the cellars. Its defence from bombs

consisted almost entirely of steel shutters fitted to the windows. In

theory, Churchill and his family were to retire to their quarters in

“The Hole” itself when the bombing grew intense. But although Churchill

did have the bed-sitting room there, he never slept the night there, but

merely used the bed to lounge on like a cherubic, cigar-smoking Madame

Récamier while he carried on discussions with his ministers who sat in

chairs surrounding him. One night during severe bombing an aide

insisted that he go down to the underground bedroom, in dererence

to Mrs Churchill’s wishes. Churchill with bad grace acquiesced, bundling

up his papers and shuffling downstairs in his slippers. He undressed, got

into bed, remained for a minute. Then he got up again, took his papers

and began making his way upstairs. The aide remonstrated but Churchill

silenced him with “I agreed to go downstairs to the bedroom . . . I have

been downstairs to the bedroom. I am now going upstairs to work and

later to sleep. We have both kept our words.”

But for Churchill

to remain indoors under any circumstances during the nights of the Blitz

was unusual. Artfully dodging an almost direct order from the King, as

well as the entreaties of his staff, he insisted not only on watching

the raids but on appearing as quickly as possible anywhere bombs had

fallen. It was during his night-bombing appearances that Churchill began

to use his V for Victory sign, a symbol inspired by a scene which took

place during the Battle of Britain. As reports of the failure of the

last great thrust of the Luftwaffe came into the Map Room, a young

officer cut out four strips of paper which he pasted round the V of the

royal cypher for “Victoria Regina” marked on the face of the clock.

Churchill, coming into the room to learn the score of the downed planes,

noted the framed “V.” For several minutes he stood looking at it in

silence, then turned abruptly and left. Thereafter, the mark which had

been born in the Map Room reappeared in the bombed streets of London and

across the world, in Churchill’ s upraised right hand, a sign of

confidence and hope.

“We Have Made History”

Also in Churchill’s underground bed-sitting room is his desk, a

continent-sized cube of well-worn mahogany, where he signed State papers

and wrote his memoranda. There are still unused envelopes in a small

stationery holder on the desk, a blunted pencil and two candlesticks. It

was at this desk that Churchill made four of his most important

broadcasts. The first was on September 11 1940, four days after the start

of the London Blitz, when he warned in rolling sentences of a battle to

come, the battle for Britain. “We cannot tell when they will come,” he

told the nation, “but no one should blind himself to the fact that a

heavy full-scale invasion of this island may be launched now. . .Every

man and woman will therefore prepare himself to do his duty, whatever

that may be, with special pride and care.”

Only four days later,

on September 15 , 1940, after being pounded by the RAF, the Luftwaffe

turned tail and fled. On October 21, 1940, when the Battle of Britain

was almost over, Churchill spoke from the bedroom a second time, this

time to the stricken French. There was no chair in the room for the

announcer, and the microphone could not be moved. So Michel Saint-Denis

had to introduce the Prime Minister while sitting on his knee. Then

Churchill spoke, in such French as can only be spoken by an Englishman.

Quoting Napoleon he said, “These same Prussians who are so boastful

today were three to one at Jena and six to one at Montmirail. Never,” he

went on, “will I believe that the soul of France is dead. Vive la

France!” “After he had finished,” recalls Saint-Denis, “there was a

silence. We were all deeply stirred. Then Churchill stood. ‘We have made

history tonight,’ he said, and his eyes were full of tears.”

Three months later, Churchill broadcast to the Italians, warning them of

the consequences of Mussolini’s recent alliance with Hitler. And on

December 8, 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour,

Churchill made his last broadcast from “The Hole.” Pledging Britain’s

support for her American allies, he told them: “Now it only remains for

the two great democracies to face their task with whatever strength God

may give them. ”

A visitor to This Secret Place once looked at

the desk and, as the guide told the story of the four speeches, said,

“All my life I have heard that when danger threatened Drake’s Drum would

beat. But I never thought it could take the form of a human voice from

behind a desk. ” The P.M. and the Sergeant-Major IF IT was the

personality of Churchill that gave This Secret Place its character, it

was the skill of George Rance that kept things running smoothly. The

relationship between the two men was a delicately poised one. Both were

old soldiers. Both were the same age: Churchill had taken power on

Rance’s birthday, and this, Rance felt, had a special significance. Of

course one was the Prime Minister and the other the custodian, but it

was more a feeling of the colonel of the Regiment and the Regimental

Sergeant-Major. If the “Old Boss,” as everyone referred to him, wanted

Rance to do something that Rance felt was out of order, Rance did not

hesitate to say so.

Once Churchill decided that his bed faced the

wrong way. Rance replied that it was all right for the Prime Minister to

want to have his bed shifted, but the fact remained that there were two

beams which prevented the shift. Churchill looked at the bed, at Rance,

and at the beams and slammed out of the room. Later word was passed to

Rance that the P.M. knew that he had acted correctly and it would be

perfectly all right if they both forgot the entire thing. Although

Churchill specialized in demanding the seemingly impossible, he asked it

only of those people he knew and whom he felt were not extending their

capabilities to their fullest stretch. They might be generals reluctant

to risk defeat, admirals wary of losing their ships, politicians fearful

of harming their careers, or ex Sergeant George Rance.

After the first meeting in the Cabinet Room, Churchill called Rance for a

private word. “Those chairs are no good,” he said. “Their seats are too

hard. I want new ones by tonight. ” “It can’t be done,” Rance answered.

“I want it done, ” Churchill thundered back. Rance could scarcely

restrain himself from stamping his foot, saluting and saying “Saahl ”

Calling the Office of Works to report that he needed 24 new chairs

delivered at the double, Rance was informed that it wasn’t possible. “I

will now tell you what the Prime Minister told me,” Rance said, and told

them. The chairs were delivered and in place for the Cabinet meeting.

A devourer of information, Churchill was also a lover of brevity on

the part of others. At Cabinet meetings if a subject was of interest to

him, he would ask for an immediate report dealing in minute detail with

every aspect of the problem all on not more than one sheet of paper. To

satisfy this, a typewriter was located whose type was almost small

enough to record the wisdom of Confucius on a grain of rice. At the same

time, when reading his own speeches Churchill demanded a type so large

that a long Churchillian sentence, complete with drum-rolls, barely went

on to one page. This, too, was supplied by Rance. Mrs Churchill, who had

her own underground room, also used by Mary Churchill when she was on

leave from her ATS anti-aircraft unit, relied on Rance, too. Her

requests were usually aimed at giving her husband what small comforts

could be found in wartime.

On one occasion, when Churchill was due to return from a journey, Rance

was asked by Mrs Churchill to think up a small surprise. Someone had

sent the Old Boss a small black wooden cat as a mascot. Rance made a

small wooden wall for the cat to peer over. Churchill was delighted with

the gift and put it on his bedside table. On the way back to his office

Rance met an august admiral who asked, “How is the Prime Minister?”

“Very well, sir, ” Rance replied. “When l left him, he was playing with

his toy cat.”

When invasion seemed imminent, preparations were made to resist should

This Secret Place be attacked. Above ground, the Home Guard manned a

pillbox at the corner of the building, and just inside the door were a

group of Grenadier Guards, named Rance’s Guard for security reasons, the

only time a private person had been so singled out in the Regiment’s

300-year history. Below, inside the fortress itself, were men of the

Royal Marines. Fitted to the walls were rifle racks. If the attack had

come, these guns would have been passed out to help hold the fortress to

the last man. The Old Boss had his service revolver from the First World

War, and in his desk was a dagger. When George VI paid a visit during

the darkest days of the war, he noticed the dagger and asked its

purpose. “For Mr Churchill, sir,” Rance replied. “So that he can use it

when Hitler is brought before him.” Mr Churchill listened but did not

add anything to the statement.

Although the pressure was intense,

the undercurrent of impish waggery which the Old Boss seemed to inspire

never vanished from This Secret Place. Since the moles, as the inmates

called themselves, lived almost entirely underground, the principal

Cabinet Ministers all had small bedrooms, and the staff were furnished

with dormitories, the weather on the surface was an unknown

quantity. To provide this information, Rance had made a board with

movable strips. These were labelled Rain, Snow, Sunny and on through all

the permutations of English weather, which were changed as reports were

telephoned below. Another board showed if London was under air attack or

not. Puckishly Ernie Bevin would invariably change the weather board

signal to Windy when bombing was reported. One day a young officer beat

Bevin to the draw by posting in the weather slot a sign from a pub

saying No Gin. Bevin prepared to make the habitual change to Windy, then

noticed the No Gin sign. “Gawd ’elp us,” he muttered, “it’s worse than

windy.” He let the sign stand.

“A Flaming Maharaja”

Early in the war Sir Archibald Sinclair, the Secretary of State for

Air, had told Churchill about one of his men who had been on duty a long

time without leave and had then collapsed when he finally got home.

“Serves him right for going on leave,” the Old Boss answered. In 1943,

after the danger of invasion was past and Britain was on the offensive,

the pressures caught up with even the indomitable Churchill himself.

After a trip to Africa, he caught pneumonia and word was passed that

“the Old Boss was laid up.” Immobilized in bed, he sent for Rance. The

ex- ergeant was shaken when he saw how pale the Prime Minister looked.

and no hint of a cigar anywhere. His voice was feeble but his words,

although slurred, were plain. He was sure that some of the pictures in

his room were not hanging properly. Would Rance adjust them?

Rance looked round the room. Portraits of Churchill’s parents hung on

the walls, a small shelf Rance had made to hold some of his trinkets was

in place, the black cat peering over the wall was on the bedside table.

He saw the picture the Old Boss meant. As he began to shift it,

Churchill’s voice seemed to grow stronger, indicating the direction the

picture ought to be moved. Finally he was satisfied, and in fact when

Rance turned round , Churchill was sitting up in bed, the ghost of his

old-time spark beginning to glitter in his eyes. “Not quite gone yet, ”

he said. “Eyes just as good as ever.” This time Rance did say

“Saah,” although when he stamped his foot it was very softly.

But after a second bout of pneumonia Churchill’s legs could no longer

manage the stairs. He continued to attend Cabinet meetings in “The

Hole,” but came downstairs in a sort of sedan chair carried by two Royal

Marines. “Looks like a flaming maharaja, don’t he?” said one of the

guards. Rance, who remembered him racing through the corridors, trailed

by a nimbus of admirals and generals, could only nod. In This Secret

Place the war had begun with Ismay glancing at his watch and saying, at

I lam on September 3, 1939, “Gentlemen, we are at war with Germany.” It

ended just as casually when, on August 16, 1945, the telephones stopped

ringing and one by one the officers left their desks.

George Rance turned out the lights in their offices, closed the doors,

and climbed the stairs into the sunshine. That was the end, almost. On

January 30, 1965 , the long, slow cortege of the funeral of Sir Winston

Spencer Churchill wound through London, from Westminster to the City.

The scars of the war had now been long obliterated. There was nothing to

mark the block which had hidden the wartime fortress, only a blank brick

wall. In St Paul’s Cathedral George Rance, 91 years old. sat in a

back pew and listened. He remembered then the few gruff words that had

passed between the ex Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal Scots Fusiliers

and the ex Sergeant of the Rifle Brigade, when the war was over. “I

suppose. Rance, ” Churchill had said, “you think I don‘t know all you

have done. Well, I do. Thank you. Thank you very much. ”

|

![]()