|

Two internet articles written in my reasoning of the above statement

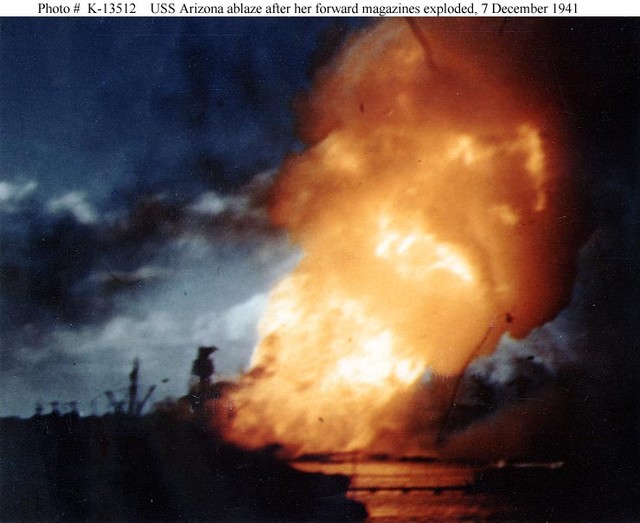

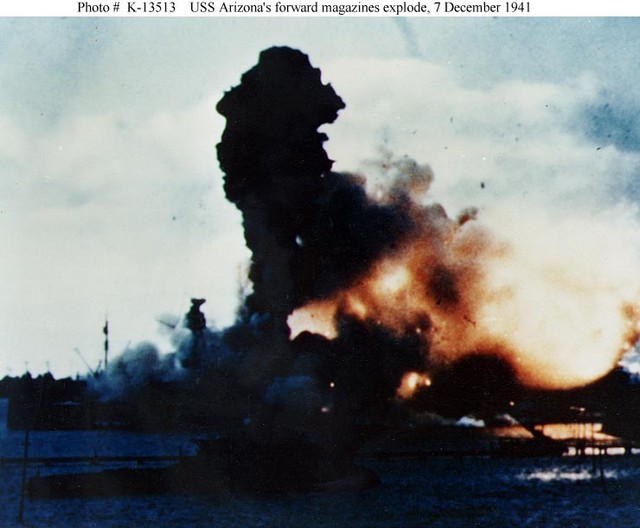

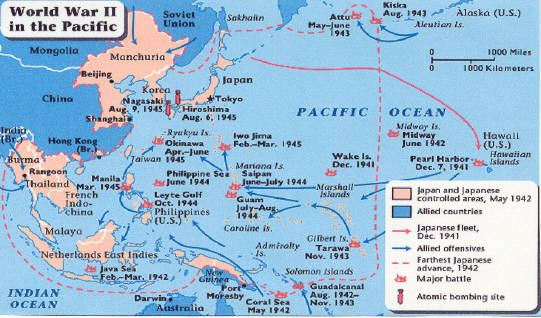

The sudden conclusion of the Pacific War with the dropping of the two

atom bombs on Hiroshima and 3 days later on Nagasaki was greeted with joy by all

Americans, and especially by the more than three and a half million soldiers,

sailors and marines preparing to invade Japan. These forces had not only to

come from the Pacific. First Army, which had fought its way from Normandy to

the heart of Germany, and Eighth Air Force, based in England, were on the way as

well. But morale was not good among veterans of the Ardennes, Guadalcanal, and

other campaigns. Soldiers who had fought across Europe saw the war as being

over, they had won. Now they were being told to prepare for another invasion;

not many thought they would survive this one.

General MacArthur's staff had twice come up with

figures exceeding 100,000 casualties for the opening months of combat on the

southern island of Kyushu, a figure which some historians largely succeeded in

contrasting favourably, and quite mistakenly, with President Harry Truman's

much-derided post-war statement that Marshall had advised him at Potsdam that

casualties from

both the Kyushu and Honshu invasion operations

could range from 250,000 to one million men. Truman and Marshall were intimately

familiar with losses in the Pacific during the previous year, over 200,000

casualties from wounds, fatigue and disease, plus 10,000 American dead and

missing in the Marianas, 5,500 dead on and around Leyte, 9,000 dead during the

Luzon campaign, 6,800 at Iwo Jima, 12,600 at Okinawa, and 2,000 killed in the

unexpectedly vicious fighting on Peleliu. Both also knew that, except for some

operations around New Guinea, real casualties were outpacing estimates and the

gap was widening. They also knew that while America always emerged victorious,

operations often were not being completed as rapidly as planned with all the

added cost in blood and treasure that such lengthy campaigns entailed.

Leyte was a perfect example. Leyte was to the Luzon campaign what the Kyushu

invasion was to the capture of Honshu's Kanto Plain and Tokyo, a preliminary

operation to create a huge staging area. Today, we can recall General MacArthur

wading ashore triumphantly in the Philippines. But what Truman and Marshall

knew only too well was that General MacArthur was supposed to have retaken Leyte

with four divisions and have eight fighter and bomber groups striking from the

island within 45 days of the initial landings. However, nine divisions and

twice as many days into the battle, only a fraction of that airpower was

operational because of unexpected terrain conditions (and

this

on an island which the United States had occupied for over forty years). The

fighting on the ground not gone as planned. The Japanese even briefly isolated

Fifth Air Force headquarters and also captured much of the Burauen airfield

complex before reinforcements pushed them back into the jungle.

Some historians have stated incredulously that Marshall's estimate of up to one

million casualties for the invasion of Japan significantly exceeded those

sustained in Europe. But while the naval side of the Pacific War displayed

broad, sweeping moves, land combat in the Pacific had little in common with the

mobile warfare that went a long way toward keeping casualties comparatively low

in France and the central German plain. The closest European commanders came

after D-Day to the corps-level combat was the prolonged fighting in the Huertgen

Forest and Normandy's hedgerows, close-in, infantry-intensive fire fights that

produced many bodies on both sides. It is also important to note that when they

went to Potsdam, Truman and Marshall knew that total US casualties had recently

exceeded the one and a quarter million mark, a number historians find

unfathomable, what's more the bulk of the losses occurred in just the previous

year of fighting against Germany.

There were plenty of estimates which confidently asserted that strategic

bombing, blockade, or both, even the invasion of Kyushu alone, would bring Japan

to its senses, but no one was able to provide General Marshall with a convincing

explanation of just how long that would take. The millions of Americans poised

to take part in the largest invasion in history, as well as those supporting

them, could only stay poised for so long. Leaders in both Washington

and Tokyo knew this just as well as their theatre commanders in the

Pacific. After learning of the bomb, MacArthur ignored it save for considering

how to integrate the new weapon into plans for tactical operations at Kyushu and

Honshu if Tokyo was not forced to the surrender table. Nimitz was of a similar

mind. On being told that the bomb would become available in August, he

reputedly remarked, "In the meantime I have a war to fight."

On 29 July 1945, there came a stunning change to an earlier report on enemy

strength on Kyushu. This update set alarm bells ringing in MacArthur's

headquarters as well as Washington because it stated bluntly that the Japanese

were rapidly reinforcing southern Kyushu and had increased troop strength from

80,000 to 206,000 men, quote: "with no end in sight." Finally, it warned that

Japanese efforts were, quote: "changing the tactical and strategic situation

sharply." While the breathless "no end in sight" claim turned out to be

somewhat overstated, the confirmed figures were ominous enough for Marshall to

ponder scraping the Kyushu operation altogether even though MacArthur maintained

that it was still the best option available.

Now, this is particularly interesting because, in recent years, some historians

have promoted the idea that Marshall's staff believed an invasion of Japan would

have been essentially a walk-over. To bolster their argument, they point to

highly qualified, and limited, casualty projections in a variety of documents

produced in May and June 1945, roughly half a year before the first invasion

operation, Olympic, was to commence. Unfortunately, the numbers in these

documents, usually 30-day estimates, have been

grossly

misrepresented by individuals with little understanding of how the estimates

were made, exactly what they represented, and how the various documents are

connected. In effect, it is as if someone during World War II came across

casualty estimates for the invasion of Sicily, and then declared that the

numbers would represent casualties from the entire Italian campaign. Then,

having gone this far, announced with

complete confidence that

the numbers actually represented likely casualties for the balance of the war

with Germany. Of course, back then, such a notion would be dismissed as being

laughably absurd, and the flow of battle would speedily move beyond the

single event the original estimates, be they good or bad, were for.

That, however, was over fifty years ago. Today, historians doing much the same

thing, win the plaudits of their peers, receive copious grants, and affect the

decisions of major institutions.

The limited and cautiously optimistic estimates of May and June 1945 were turned

to junk by that intelligence estimate at July's end, and the situation was even

more dangerous than was perceived at that time. War plans called for the

initial landings on the main Japanese islands to be conducted approximately 90

days hence. But the invasion of Kyushu would actually have not been able to

take place for anywhere from 120 to 135 days, a disastrous occurrence for the

successful outcome of stated US war aims.

Some today assert, in effect, that it would have been more humane to have just

continued the conventional B-29 bombing of Japan, which in six months had killed

nearly 300,000 people and displaced or rendered homeless over 8 million more.

They also assert that the growing US blockade would have soon forced a surrender

because the Japanese faced, quote: "imminent starvation." US Planners at the

time, however, weren't nearly so bold, and the whole reason why advocates of

tightening the noose around the main Japanese islands came up with so many

different estimates of

when blockade and bombardment might force

Japan to surrender was because the situation wasn't nearly as cut and dried as

it appears today, even when that nation's supply lines were severed. Japan

would indeed have become, quote: "a nation without cities," as urban

populations suffered grievously under the weight of Allied bombing; but over

half the population during the war lived and worked on farms. Back then the

system of price supports that has encouraged Japanese farmers today to convert

practically every square foot of their land to rice cultivation

did not

exist. Large vegetable gardens were a standard feature of a family's

land and wheat was also widely grown.

The idea that the Japanese were about to run out of food any time soon was

largely derived from repeated misreading of the

Summary Report

of the 104 volume US Strategic Bombing Survey of Japan. Using Survey findings,

Craven and Cate, in the multi-volume US Army Air Force history of WWII detailed

the successful US mine-laying efforts against Japanese shipping which

essentially cut Japanese oil and food

imports, and state only

that by mid-August, quote: "the calorie count of the average man's fare had

shrunk dangerously." Obviously, some historians enthusiasm for the point they

are trying to make has gotten the better of them since the reduced nutritional

value of meals is somewhat different than "imminent starvation."

As for the Imperial Army itself, it was in somewhat better shape than is

commonly understood today. Moreover, the Japanese had

figured the US

out. They had

correctly deduced the landing beaches and

even the approximate times of

both invasion operations, and were

thus presented with

huge tactical and even strategic

possibilities. And although the Japanese had never perfected central control

and massed fire of their artillery, this fact was largely irrelevant under such

circumstances. The months that the Japanese Sixteenth Army had to wait for the

first US invasion, at Kyushu, were not going to be spent with its soldiers and

the island's massive civilian population sitting on their duffs. The ability to

dig in and pre register, dig in and pre register, dig in and pre register,

cannot be so casually dismissed. To borrow a phrase from a recent Asian war,

the Kyushu invasion areas were going to be a target-rich environment where

artillery was going to methodically do its work on a large number of soldiers

and Marines whose luck had run out. On Okinawa, the US Tenth Army commander,

General Buckner, was killed by artillery fire when the campaign was ostensibly

in the mopping-up phase, and from World War I to the fighting in Grosny, where

shells killed a Russian two-star general, there is ample evidence of artillery

living up to its deadly reputation.

It has also been stated that US ground troops didn't really need to worry about

Japanese cave defences since combat experience in the Pacific, and tests run in

the US, proved the effectiveness of self-propelled 8-inch and 155mm howitzer

against caves and bunkers as well as their vulnerability to direct fire from

tanks. That the Japanese were

also well aware of this and were

arranging defensive positions accordingly from lessons learned on Okinawa and

the Philippines is not mentioned. In any event, the Japanese had already

demonstrated that they could, with the right terrain, construct strong points

which could not be bypassed and had to be reduced without benefit of

any

direct-fire weapons since no tanks, let alone lumbering self-propelled guns,

could work their way in for an appropriate shot.

Similarly, on the Japanese ability to defend against US tanks, Army and Marine

armour veterans of the Pacific war would be amazed to learn that they had little

to fear during the invasion. After all, Japan's obsolescent 47mm anti-tank

guns, quote: "could penetrate the M-4 Sherman's armour only in vulnerable

spots at very close range" and that their older 37mm gun was completely

ineffective against the Sherman tank. In fact, the Japanese, through hard

experience, were becoming quite adept at tank killing. During two actions in

particular on Okinawa, they managed to knock out 22 and 30 Sherman's

respectively. In one of these fights, Fujio Takeda managed to stop four tanks

with six 400-yard shots from his supposedly worthless 47mm. As for the 37mm,

it was not intended to actually destroy tanks during the invasions but to

immobilize them at very short ranges so that they would become easier prey for

the infantry tank-killing teams that had proven so effective on Okinawa.

Some historians are also somewhat more confident than on-scene commanders as to

our ability to pulverize Japanese defences. This may be due, in part, to an

overly literal interpretation of what the Japanese meant by "beach defences,"

even though there is ample documentation on their efforts to develop positions

well inland, out of range of the Navy's big guns. One author, from the safe

distance of five decades wrote: "That coastal defence units could have survived

the greatest pre-invasion bombardment in history to fight a tenacious, organized

beach defence was highly doubtful." I do believe something similar to this was

confidently maintained just before the Somme in 1916, and it is worthwhile

noting that every square inch of Iwo Jima and Okinawa was well

within the range of the Navy's 8, 12, 14, and 16 inch guns during those

campaigns.

Points like these may sound rather nit-picky but they

assume great importance when you realize that, as noted earlier, the target date

for Kyushu of 1 November 1945 was going to get pushed back as much as 45 days,

giving the Japanese as much as four and a half months from the flashing red

light of the 29 July intelligence estimate to prepare their defences.

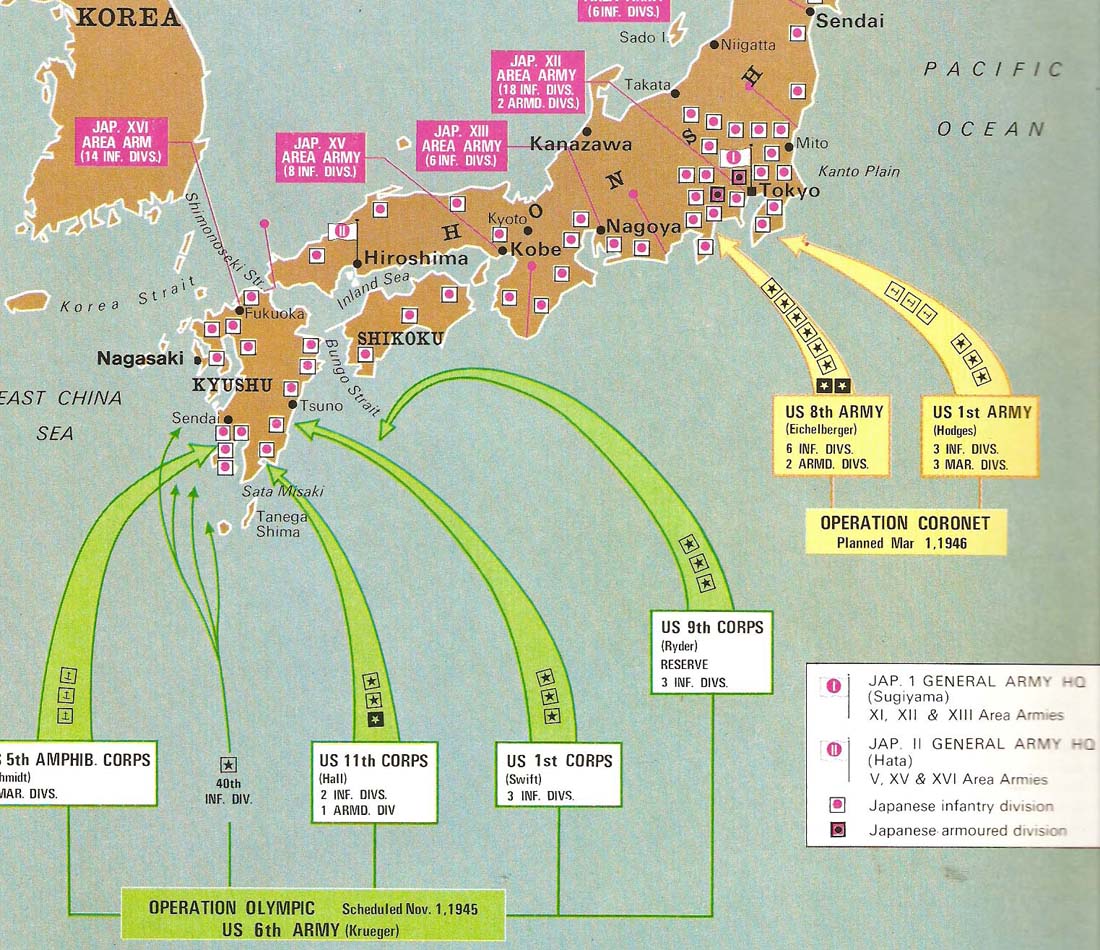

The Joint Chiefs originally set the date for the invasion of Kyushu (Operation

Olympic) as X-Day, December 1, 1945, and for Honshu (Operation Coronet) as

Y-Day, March 1, 1946. To lessen casualties, the launch of Coronet would await

the arrival of two armoured divisions from Europe to

sweep up

Honshu's Kanto Plain and cut off Tokyo before the seasonal monsoons turned it

into vast pools of rice, muck, and water crisscrossed by elevated roads and

dominated by rugged, well-defended foothills.

Now, long before the British experienced the tragedy of pushing XXX Corps up a

single road through the Dutch lowlands to Arnhem, an event popularised through

the book and movie

A Bridge too Far, US planners were well aware

of the costs that would be incurred if the Kanto Plain was not secured for

mobile warfare and airfield construction prior to the wet season. Intensive

hydrological and weather studies begun in 1943 made it clear that an invasion in

early March offered the best chance of success, with the situation becoming more

risky as the month progressed.

With good luck, relatively free movement across the plain

might

even be possible well into April. Unfortunately, this assumed that the snow

run-off from the mountains would not be too severe, and that the Japanese would

not flood the fields. While subsequent post-war prisoner interrogations did

not reveal any plans to

systematically deluge low-lying areas, a

quick thrust up the Kanto Plain would not have been as speedy as planners

believed. First, there were no bridges in the area capable of taking vehicles

over 12 tons. Every tank, every self-propelled gun, and prime mover would have

to cross bridges erected for the event. Next, logistical considerations and the

sequence of follow-up units would require that armoured divisions not even land

until Y+10. This would provide time for the defenders to observe that the US

infantry's generic tank support was severely hampered by already flooded rice

fields and- shall we say-

suggest ways to make things worse for

the invaders.

A late start on Honshu would leave American forces to fight their way up flood

plains that were only dry during certain times of the year, but could be

suddenly inundated by the Japanese. If the timetable slipped for either

operation, US soldiers and Marines on Honshu would risk fighting in terrain

similar to that later encountered in Vietnam, minus the helicopters to fly over

this mess, where all movement was readily visible from even low terrain features

and vulnerable convoys moved on roads above rice paddies. Unfortunately, foul

weather would have delayed base development on Kyushu and spelled a potentially

disastrous late start for the operation on Honshu.

Planners envisioned the construction of 11 airfields on Kyushu for the massed

airpower which would soften up Honshu. Bomb and fuel storage, roads, wharves,

and base facilities would be needed to support those air groups plus the US

Sixth Army holding a 110 mile stop-line one third of the way up the island. All

plans centred on construction of the

minimum essential operating

facilities. But that minimum grew. The 31 air groups was increased to 40 then

to 51, all for an island on which there was considerably

less terrain information available than the US erroneously believed we knew

about Leyte. Numerous airfields would come on line early to support ground

operations on Kyushu, but the lengthy strips and support facilities for Honshu

bound medium and heavy bombers would only start to become available 45 days into

the operation. Most were not projected to be ready until 90 to 105 days after

the initial landings on Kyushu in spite of a massive effort.

The constraints on the air campaign were so clear that when the Joint Chiefs set

the target dates of the Kyushu and the Honshu invasions for December 1, 1945 and

March 1, 1946, respectively, it was apparent that the three-month period between

X Day, Olympic and Y Day, Coronet, would

not be sufficient.

Weather ultimately determined which operation to reschedule because Coronet

could not be moved back without moving it closer to the monsoon season and thus

risking serious restrictions on the ground campaign from flooded fields, and the

air campaign from cloud cover that almost doubles from early March to early

April. MacArthur proposed bumping the Kyushu invasion ahead by a month. As

soon as this was pointed out, both Nimitz and the Joint Chiefs in Washington

immediately agreed. Olympic was moved forward one month to November 1, which

also gave the Japanese less time to dig in.

Unfortunately these best-laid plans would not have unfolded as expected even if

the atom bombs had not been dropped and the Soviet entry into the Pacific War

had not frustrated Tokyo's last hope of reaching a settlement

short

of unconditional surrender, a Versailles like outcome unacceptable to Truman and

many of his contemporaries because it was seen as an incomplete victory that

could well require the next generation to

re fight the war. An

infinitely bigger war than the late unpleasantness in Vietnam, which would have

seen us sending troops overseas in 1965 to fight Japan instead of to Southeast

Asia. The end result of this delay would have been an even more costly campaign

on Honshu than was predicted. A blood bath in which pre-invasion casualty

estimates rapidly became meaningless because of something that the defenders

could not achieve on their own, but a low pressure trough would, knock the

delicate US timetable off balance.

The Divine Wind, or Kamikaze, a powerful typhoon, destroyed a foreign invasion

force heading for Japan in 1281, and it was for this storm that Japanese suicide

aircraft of World War II were named. On October 9, 1945, a similar typhoon

packing 140-mile per hour winds struck the American staging area on Okinawa that

would have been expanded to capacity by that time if the war had not ended in

September, and was still crammed with aircraft and assault shipping much of

which was destroyed. US analysts at the scene reported that the storm would

have caused up to a 45 day delay in the invasion of Kyushu. The point that

goes begging, however, is that while these reports from the Pacific were correct

in themselves, they did not make note of the critical significance that such a

delay, well past the initial and

unacceptable target date of

December 1, would have on base construction on Kyushu, and consequently mean for

the Honshu invasion, which would have then been pushed back as far as mid April

1946.

If there had been no atom bombs and Tokyo had attempted to hold out for an

extended time, a possibility that even bombing and blockade advocates granted,

the Japanese would have immediately appreciated the impact of the storm in the

waters around Okinawa. Moreover, they would know

exactly what

it meant for the follow up invasion of Honshu, which they had predicted as

accurately as the invasion of Kyushu. Even with the storm delay and friction of

combat on Kyushu, the Coronet schedule would have led US engineers to perform

virtual miracles to make up for lost time and implement Y Day as early in April

as possible. Unfortunately the Divine Winds packed a one two punch.

On 4 April 1946, another typhoon raged in the Pacific, this one striking the

northernmost Philippine island of Luzon on the following day where it inflicted

only moderate damage before moving toward Taiwan. Coming almost a year after

the war, it was of no particular concern. The

Los Angeles Times

gave it about a paragraph on the bottom of page 2. But if Japan had held out,

this storm would have had profound effects on the world we live in today. It

would have been the closest watched weather cell in history. Would the storm

move to the west after hitting Luzon, the Army's main staging area for Coronet,

or would it take the normal spiralling turn to the north, and then northeast as

the October typhoon? Would slow, shallow-draft landing craft be caught at sea

or in the Philippines where loading operations would be put on hold? If they

were already on their way to Japan, would they be able to reach Kyushu's

sheltered bay? And what about the breakwater caissons for the massive

artificial harbour to be assembled near Tokyo? The construction of the

harbour's prefabricated components carried a priority second

only

to the atom bomb, and this precious towed cargo could not be allowed to fall

victim to the storm and be scattered across the sea.

Whatever stage of employment US forces were in during those first days of April,

a delay of some sort, certainly no less than a week and perhaps much,

much more, was going to occur. A delay that the two US field armies

invading Honshu, the First and Eighth, could ill afford and that Japanese

militarists would see as yet another sign that they were right after all.

This is

critical. Various authors have noted that

much of the land today contains built-up areas not there in 1946, but are

blissfully unaware that, thanks to the delays, anyone treading this same, quote:

"flat, dry tank country" in 1946 would, in reality, have been up to their calves

in muck and rice shoots by the time the invasion actually took place.

Recent years have also seen the claim that the kamikaze threat was overrated.

Time does not allow the subject to be discussed in any sort of detail here, but

one aspect is worth emphasizing: US intelligence turned out to be dead wrong

about the number of Japanese planes available to defend the Japanese Islands.

Estimates that 6,700 could be made available in stages, grew to only 7,200 by

the time of the surrender. This number, however, turned out to be short by some

3,300 in light of the armada of 10,500 planes which the enemy planned to expend

in stages during the opening phases of the invasion operations, most as

Kamikazes. (see below**). All guesswork aside, occupation authorities after the war found that

the number of military aircraft actually available in the Home Islands was over

12,700. Another thing about those 3,300 undetected aircraft, it is worthwhile

remembering that, excluding aircraft that returned to base, the Japanese

actually expended well under half that number as Kamikazes at Okinawa, roughly

1,400, where over 5,000 US sailors were killed.

Of course, to some, all this discussion about the surprise 3,300 kamikaze

aircraft, the delay of the Honshu landing until the rice paddies were flooded,

etc., is all moot because the Japanese were supposedly just itching to surrender

even before the dropping of the atom bombs and the Soviet Union's entry into the

war.

(**It is now believed that the

Japanese only had approx 800 kamikaze planes to throw against any invasion

fleet.)

Adapted From: Transcript of

"OPERATION DOWNFALL [US invasion of Japan]: US PLANS AND JAPANESE

COUNTER-MEASURES" by D. M. Giangreco, US Army Command and General Staff College,

16 February 1998.

Being badly typed, this has been amended and

"anglicised" by myself on 4 Oct 02.

Why America Was Right To

Drop The Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima & Nagasaki

With evidence

from an article by James Martin Davis

http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb525-The-Atomic-Bomb-and-the-End-of-World-War-II/

Deep in the recesses of the

National Archives in Washington, DC, hidden for over five decades, lie thousands

of pages of yellowing and dusty documents. These documents, which are now

declassified, still bear the stamp, "Top Secret." Contained in these little

examined documents are the detailed plans for "Operation Downfall," the code

name for the scheduled American invasion of Japan. Only a few Americans in 1945,

and fewer Americans today, are aware of the elaborate plans that had been

prepared for the American invasion of the Japanese home islands. Even fewer are

aware of how close America actually came to launching that invasion and of what

the Japanese had in store for us had the invasion of Japan actually been

launched. "Operation Downfall" was prepared in its final form during the spring

and summer of 1945. this plan called for two massive military undertakings to be

carried out in succession, and aimed at the very heart of the Japanese Empire.

In the first invasion, in what was code named "Operation Olympic", American

combat troops would be landed by amphibious assault during the early morning

hours of November 1, 1945, on Japan itself. After an unprecedented naval and

aerial bombardment, 14 combat divisions of American soldiers and marines would

land on heavily fortified and defended Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese

home islands. On March 1, 1946, the second invasion, code named "Operation

Coronet", would send at least 22 more American combat divisions against one

million Japanese defenders to assault the main island of Honshu and the Tokyo

Plain in a final effort to obtain the unconditional surrender of Japan.

With the exception of a part of the British Pacific Fleet, "Operation Downfall"

was to be a strictly American operation. It called for the utilization of the

entire United States Marine Corps, the employment of the entire United States

Navy in the Pacific, and for the efforts of the 7th Air Force, the 8th Air Force

recently deployed from Europe, the 20th Air Force, and for the American Far

Eastern Air Force. Over 1.5 million combat soldiers, with millions more in

support, would be directly involved in these two amphibious assaults. A total of

4.5 million American servicemen, over 40% of all servicemen still in uniform in

1945, were to be a part of "Operation Downfall." The invasion of Japan was to be

no easy military undertaking and casualties were expected to be extremely heavy.

Admiral William Leahy estimated that there would be over 250,000 Americans

killed or wounded on Kyusky alone. General Charles Willoughby, MacArthur's Chief

of Intelligence, estimated that American casualties from the entire operation

would be one million men by the fall of 1946. General Willoughby's own

intelligence staff considered this to be a conservative estimate. During

the summer of 1945, America had little time to prepare for such a monumental

endeavour, but our top military leaders were in almost unanimous agreement that

such an invasion was necessary.

While a naval blockade and strategic bombing of Japan was considered to be

useful, General Douglas MacArthur considered a naval blockade of Japan

ineffective to bring about an unconditional surrender. General George C.

Marshall was of the opinion that air power over Japan as it was over German,

would not be sufficient to bring an end to the war. While most of our top

military minds believed that a continued naval blockade and the strategic

bombing campaign would further weaken Japan, few of them believed that the

blockade or the bombing would bring about her unconditional surrender. The

advocates for invasion agreed that while a naval blockade chokes, it does not

kill; and though strategic bombing might destroy cities, it still leaves whole

armies intact. Both General Dwight D. Eisenhower and General Ira C. Eaker, the

Deputy Commander of the Army Air Force agreed. So on May 25, 1945, the Combined

Chiefs of Staff, after extensive deliberation, issued to MacArthur, to Admiral

Chester Nimitz, and to Army Air Force General "Hap" Arnold, the Top Secret

directive to proceed with the invasion of Kyushu. The target date was set, for

obvious reasons after the typhoon season, for November 1, 1945. On July

24th, President Harry S. Truman approved the report of the Combined Chiefs of

Staff, which called for the initiation of Operations "Olympic" and "Coronet." On

July 26th, the United Nations issued the Potsdam Proclamation, which called upon

Japan to surrender unconditionally or face "total destruction." Three days

later, on July 29th, DOMEI, the Japanese governmental news agency, broadcast to

the world that Japan would ignore the proclamation of Potsdam and would refuse

to surrender.

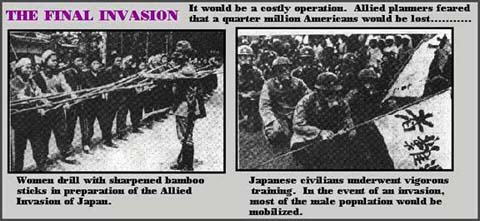

During this same time period, the intelligence section of the Federal

Communications Commission monitored internal Japanese radio broadcasts, which

disclosed that Japan had closed all its schools to mobilize its school

children---it was arming its civilian population and forming it into national

civilian defence units, and that it was turning Japan into a nation of fortified

caves and underground defences in preparation for the expected invasion of their

homeland.

"Operation Olympic", the invasion of Kyushu, would come first. Olympic called

for a four-pronged assault from the sea on Kyushu. Its purpose was to seize and

control the southern one-third of that island and to establish American naval

and air bases there in order to effectively intensify the bombings of Japanese

industry, to tighten the naval blockade of the home islands, to destroy units of

the main Japanese army, and to support "Coronet", the scheduled invasion of the

Tokyo Plain, that was to come the following March. On October 27th, the

preliminary invasion would begin with the 40th Infantry Division would land on a

series of small islands to the west and southwest of Kyushu. At the same time,

the 158th Regimental Combat Team would invade and occupy a small island 28 miles

to the south of Kyushu. On these islands, seaplane bases would be established

and radar would be set up to provide advance air warning for the invasion fleet,

to serve as fighter direction centres for the carrier based aircraft and to

provide advance air warning for the invasion fleet, should things not go well on

the day of the invasion. As the invasion grew imminent, the massive power of the

United States Navy would approach Japan. The naval forces scheduled to take part

in the actual invasion consisted of two awesome fleets---the Third and the

Fifth. The Third Fleet, under Admiral "Bull" Halsey, with its big guns and

naval aircraft, would provide strategic support for the operation against Honshu

and Hokkaido in order to impede the movement of Japanese reinforcements south to

Kyushu. The third Fleet would be composed of a powerful group of battleships,

heavy cruisers, destroyers, dozens of support ships, plus three fast carrier

task groups. From these fast carriers, hundreds of Navy fighters, dive bombers

and torpedo planes would hit targets all over the island of Honshu. The

Fifth Fleet, under Admiral Spruance, would carry our invasion troops. This Fleet

would consist of almost 3,000 ships, including fast carriers and escort carrier

task forces, a gunfire and covering force for bombardment and fire support, and

a joint expeditionary force. This expeditionary force would include thousands of

additional landing craft of all types and sizes.

Several days before the invasion, the battleships, heavy cruisers and destroyers

would pour thousands of tons of high explosives into the target areas, and they

would not cease the bombardment until after the landing forces had been

launched. During the early morning hours of November 1, 1945, the actual

invasion would commence. Thousands of American soldiers and marines would pour

ashore on beaches all along the eastern, south eastern, southern and western

coasts of Kyushu. The Eastern Assault Force, consisting of the 25th, 33rd

and the 41st Infantry Divisions, would land near Miyaski, at beaches called

Austin, Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Chrysler, and Cord (?) (Ford?) and move

inland to attempt to capture this city and it's nearby airfield. The Southern

Force, consisting of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 43rd Division and American

Division would land inside Ariake Bay at beaches labeled DeSoto, Dusenberg,

Essex, Ford and Franklin and attempt to capture Shibushi and to capture, further

inland, the city of Kanoya and its surround airfield. On the western shore of

Kyushu, at beaches Pontiac, Reo, Rolls Royce, Saxon, Star, Studebaker, Stutz,

Winton and Zephyr, the V Amphibious Corps would land the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Marine

Divisions, sending half of its force inland to Send and the other half to the

port city of Kagoshima. On November 4th, the reserve force, consisting of the

81st and 98th Infantry Division, and the 11th Airborne Division, after feigning

an attack off the island of Shikoku would be landed, if not needed elsewhere,

near Kaimondake, near the southern most tip of Kagoshima Bay, at beaches

designated Locomobile, Lincoln, LaSalle, Hupmobile, Moon, Mercedes, Maxwell,

Overland, Oldsmobile, Packard and Plymouth.

The objective of "Olympic" was to seize and control the island of Kyushy in

order to use it for the launching platform for "Coronet", which was hoped to be

a final knockout blow aimed at Tokyo and the Kanto Plain. "Olympic" was not just

a plan for invasion, but for conquest and occupation as well. It was expected to

take four months to achieve its objective, with three fresh American Divisions

per month to be landed in support of that operation if needed. These additional

troops were to be taken from the untis scheduled for "Coronet." If all

went well with "Olympic", on March 1, 1946, "Coronet" would be launched.

"Coronet" would be twice the size of "Olympic", with as many as 28 American

Divisions to be landed on Honshu, the main Japanese island. On March 1, 1946,

all along the coast east of Tokyo, the American 1st Army would land the 5th,

7th, 27, 44th, 86th and 96th Infantry divisions along with 1st, 4th, and 6th

Marine Divisions. At Sagami Bay, just south of Tokyo, the entire 8th and 10th

Armies would strike north and east to clear the long western shore of Tokyo Bay,

and attempt to go as far as Yokohoma. The assault troops, landing to the south

of Tokyo would be the 4th, 6th, 8th, 24th, 31st, 32nd, 37th, 38th, and 87th

Infantry Divisions, along with the 13th and 20th Armoured Divisions.

Following the initial assault, eight more Divisions---the 2nd, 28th, 35th, 91st,

97th and 104th Infantry Divisions and the 11th Airborne division--- would be

landed. If additional troops were needed, as expected, other Divisions

re-deployed from Europe and undergoing training in the United States would be

shipped to Japan in what was hoped to be the final push.

US Anti Aircraft

The

key to victory in Japan rested with the success of "Olympic" at Kyushu. Without

the success of the Kyushu campaign, "Coronet" might never be launched. The key

to victory in Kyushu rested with our firepower, much of which was to be

delivered by carrier launched aircraft. At the outset of the invasion of Kyushu,

waves of Helldivers, Dauntless dive Bombers, Avengers, Corsairs and Hellcats

would take off to bomb, rocket and strafe enemy defences, gun emplacements and

troop concentrations along the beaches. In all, there would be 66 aircraft

carriers loaded with 2,649 naval and marine aircraft to be used for close-in air

support for the soldiers hitting the beaches. These planes were also the fleet's

primary protection against Japanese attack from the air. Had "Olympic" begun,

these planes would be needed to provide an umbrella of protection for the

soldiers and sailors of the invasion. Captured Japanese documents and post-war

interrogation of Japanese military leaders disclose that our intelligence

concerning the number of Japanese planes available for the defence of the home

islands was dangerously in error. In the last months of the war, our

military leaders were deathly afraid of the Japanese "kamikaze" and with good

cause. During Okinawa alone, Japanese aircraft sank 32 ships and damaged over

400 others. During the summer months, our top brass had concluded that the

Japanese had spent their air force , since American bombers and fighters flew

unmolested over the shores of Japan on a daily basis. What our military leaders

did not know was that by the end of July, 1945, as part of the Japanese overall

plan for the defence of their country, they had been saving all aircraft, fuel

and pilots in reserve, and had been feverishly building new planes for the

decisive battle for their homeland. The Japanese had abandoned, for a time,

their suicide attacks in order to preserved their pilots and planes to hurl at

our invasion fleets.

The plan for the final defence of Japan was called "Ketsu-Go", and a large part

of that plan called for the use of the Japanese Naval and Air Forces in defence.

Japan had been divided into districts, and in each of these districts hidden

airfields were being built and hangers and aircraft were being dispersed and

camouflaged in great numbers. Units were being trained, deployed and given final

instructions. Still other suicide units were being scattered throughout the

islands of Kyushu and elsewhere, and held in reserve; and for the first time in

the war, the Army and Navy Air Forces would be operating under one single

unified command. As part of the "Ketsu-Go", the Japanese were building 20

suicide take-off strips in southern Kyushu, with underground hangers for an

all-out offensive. In Kyushu alone, the Japanese had 35 camouflaged airfield and

9 seaplane bases. As part of their overall plan, these seaplanes were to be used

in suicide missions as well. On the night before the invasion, 50 seaplane

bombers, along with 100 former carrier aircraft and 50 land based army planes

were to be launched in a direct suicide attack on the fleet.

The Japanese 5th Naval Air Fleet and the 6th Air Army had 58 more airfields on

Korea, Western Honshu and Shikoku, which also were to be used for massive

suicide attacks. Allied intelligence had established that the Japanese had no

more than 2,500 aircraft of which they guessed only 300 would be deployed in

suicide attacks. However, in August of 1945, unknown to our intelligence, the

Japanese still had 5,651 Army and 7,074 Navy aircraft, for a total of 12,725

planes of all types. During July alone, 1, 131 new planes were built and almost

100 new underground aircraft plants were in various stages of construction.

Every village had some type of aircraft manufacturing activity. Hidden in mines,

railway tunnels, under viaducts and in basements of department stores, work was

being done to construct new planes. Additionally, the Japanese were

building newer and more effective models of the "Okka" which was a rocket

propelled bomb, much like the German V-1, but piloted to its final destination

by a suicide pilot. In March of 1945, the Japanese had ordered 750 of the

earlier models of the "Okka" to be produced. These aircraft were to be launched

from other aircraft. By the summer of 1945, the Japanese were building the newer

models, which were to be catapulted out of caves in Kyushu to be used against

the invasion ships which would be only minutes away. At Okinawa, while

almost 10,000 sailors died, as a result of kamikaze attacks, the kamikaze there

had been relatively ineffective, primarily because of distance. Okinawa was

located 350 miles from Kyushu and even experienced pilots flying from Japan

became lost, ran out of fuel or did not have sufficient flying time to pick out

a suitable target. Furthermore, early in the Okinawa campaign, the Americans had

established a land based fighter command which, together with the carrier

aircraft, provided an effective umbrella of protection against kamikaze attacks.

During "Olympic", the situation would be reversed. Kamikaze pilots would have

little distance to travel, would have considerable staying time over the

invasion fleet, and would have little difficulty picking out suitable targets.

Conversely, the American land based aircraft would be able to provide only

minimal protection against suicide attacks, since these American aircraft would

have little flying time over Japan before they would be forced to return to

their bases on Okinawa and elsewhere to refuel.

Also, different from Okinawa would be the Japanese choice of targets. At Okinawa

aircraft carriers and destroyers were the principal targets of the kamikaze. the

targets for the "Olympic" invasion were to be the transports carrying the

American troops who were to participate in the landing. The Japanese concluded

they could kill far more Americans by sinking one troop ship than they could by

sinking 30 destroyers. their aim was to kill thousands of American troops at

sea, thereby removing them from the actual landing. "Ketsu-Go" called for the

destruction of 700 to 800 American ships. When invasion became imminent, "Ketsu-Go"

called for a four-fold aerial plan of attack. While American ships were

approaching Japan, but still in the open seas, an initial force of 2,000 army

and navy fighters were to fight to the death in order to control the skies over

Kyusku. A second force of 330 specially trained navy combat pilots were to take

off and attack the main body of the task force to keep it from using its fire

support and air cover to adequately protect the troops carrying transports.

While these two forces were engaged, a third force of 825 suicide planes was to

hit the American transports in the open seas. As the convoys approached

their anchorage's, another 2,000 suicide planes were to be detailed in waves of

200 to 300, to be used in hour by hour attacks that would make Okinawa seem tame

in comparison.

American troops would be arriving in approximately 180 lightly armed transports

and 70 cargo vessels. Given the number of Japanese planes and the short distance

to target, certainly a number of the troop carrying transports would have hit.

By mid-morning of the first day of the invasion, most of the American land based

aircraft would be forced to return to their bases, leaving the defence against

the suicide planes to the carrier pilots and the shipboard gunners. Initially,

these pilots and gunners would have met with considerable success, but after the

third, fourth and fifth waves of Japanese aircraft, a significant number of

kamikaze most certainly would have broken through. Carrier pilots crippled

by fatigue would have to land time and time again to rearm and refuel. Navy

fighters would break down from lack of needed maintenance. Guns would

malfunction on both aircraft and combat vessels from the heat of continuous

firing, and ammunition expended in such abundance would become scarce. Gun crews

would be exhausted by nightfall, but still the waves of kamikazes would

continue. With our fleet hovering off the beaches, all remaining Japanese

aircraft would be committed to non stop mass suicide attacks, which the Japanese

hoped could be sustained for ten days.

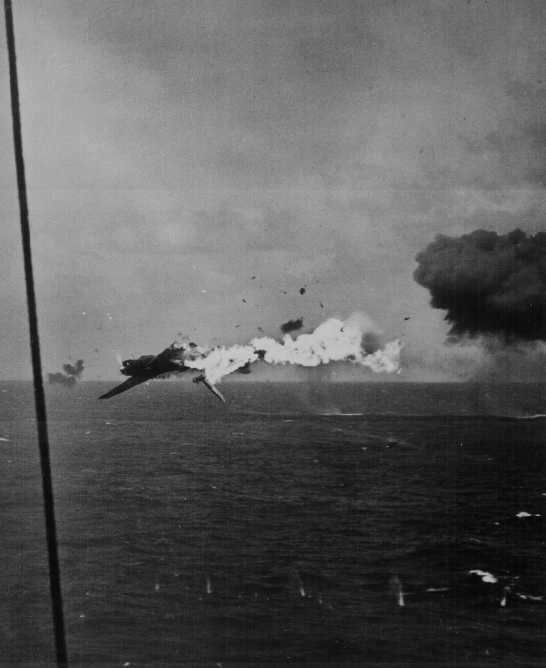

This Japanese Kamikaze pilot did not find his intended

target

The Japanese planned to coordinate their kamikaze and conventional air strikes

with attacks from the 40 remaining conventional submarines from the Japanese

Imperial Navy, beginning when the invasion fleet was 180 miles off Kyushu. As

our invasion armada grew nearer, the rate of submarine attacks would increase.

In addition to attacks by the remaining fleet submarines, some of which were to

be armed with "Long Lance" torpedoes with a range of 20 mines, the Japanese had

more frightening plans for death from the sea. By the end of the war, the

Imperial Japanese Navy still had 23 destroyers and two cruisers which were

operational. These ships were to be used to counterattack the American invasion

and a number of the destroyers were to be beached along the invasion beaches at

the last minute to be used as anti-invasion gun platforms. As early as

1944, Japan had established a special naval attack unit, which was the

counterpart of the special attack units of the air, to be used in the defence of

the homeland. These units were to be saved for the invasion and would make

widespread use of midget submarines, human torpedoes and exploding motorboats

against the Americans.

Once offshore, the invasion fleet would be forced to defend not only against the

suicide attacks from the air, but would also be confronted with suicide attacks

from the sea. Attempting to sink our troop carrying transports would be

almost 300 Kairyu suicide submarines. these two-man subs carried a 1,320 pound

bomb in their nose and were to be used in close-in ramming attacks. By the end

of the war, the Japanese had 215 Kairyu available with 207 more under

construction. With a crew of five, the Japanese Koruy suicide submarine,

carrying an even larger explosive charge, was also to be used against the

American vessels. by August, the Japanese had 115 Koryu completed, with 496

under construction.

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-fornv/japan/japtp-ss/kaiten.htm

Especially feared by our Navy were the Kaitens, which were difficult to detect,

and which were to be used against our invasion fleet just off the beaches. These

Kaitens were human torpedoes over 60 feet long, each carried a warhead of over

3,500 pounds and each was capable of sinking the largest of American naval

vessels. The Japanese had 120 shore-based Kaitens, 78 of which were in the

Kyushu area as early as August. Finally, the Japanese had almost 4,000

Navy Shinyo and Army Liaison motor boats, which were also armed with high

explosive warheads, and which were to be used in night time attacks against our

troop carrying ships. The principal goal of the special attack units of

the air and of the sea was to shatter the invasion before the landing. By

killing the combat troops aboard ships and sinking the attack transports and

cargo vessels, the Japanese were convinced the Americans would back off or

become so demoralized that they would then accept a less than unconditional

surrender and a more honourable and face-saving end for the Japanese. In

addition to destroying as many of the larger American ships as possible, "Ketsu-Go"

also called for the annihilation of the smaller offshore landing craft carrying

our G.I.'s to the invasion beaches.

The Japanese had devised a network of beach defences, consisting of

electronically detonated mines farthest offshore, three lines of suicide divers,

followed by magnetic mines and still other mines planted all over the beaches

themselves. A fanatical part of the last line of maritime defence was the

Japanese suicide frogmen, called "Fukuryu." These "crouching dragons", were

divers armed with lunge mines, each capable of sinking a landing craft up to 950

tons. There divers, numbering in the thousands, could stay submerged for up to

ten hours, and were to thrust their explosive charges into the bottom of landing

craft and, in effect, serve as human mines. As horrible as the defence of

Japan would be off the beaches, it would be on Japanese soil that the American

armed forces would face the most rugged and fanatical defence that had ever been

encountered in any of the theatres during the entire war. Throughout the

island-hopping Pacific campaign, our troops had always outnumbered the Japanese

by two and sometimes three to one. In Japan it would be different. by virtue of

a combination of cunning , guesswork and brilliant military reasoning, a number

of Japan's top military leaders were able to astutely deuce, not only when, but

where, the United States would land their first invasion forces. The Japanese

positioned their troops accordingly. Facing the 14 American Divisions landing at

Kyushu would be 14 Japanese Divisions, 7 independent mixed brigades, 3 tank

brigades and thousands of specially trained Naval Landing forces. On Kyushu the

odds would be three to two in favour of the Japanese, with 790,000 enemy

defenders against 550,000 Americans. This time the bulk of the Japanese

defenders would not be the poorly trained and ill-equipped labour battalions

that the Americans had faced in the earlier campaigns. The Japanese defenders

would be the hard-core of the Japanese Home Army. These troops were well fed and

well equipped and were linked together all over Kyushu by instantaneous

communications. They were familiar with the terrain, had stockpiles of arms and

ammunition, and had developed an effective system of transportation and

re-supply almost invisible from the air. Many of these Japanese troops were the

elite of the Japanese army, and they were swollen with a fanatical fighting

spirit that convinced them that they could defeat these American invaders that

had come to defile their homeland.

Coming ashore, the American Eastern amphibious assault forces at Miyazaki would

face the Japanese 154th Division which straddled the city, the Japanese 212th

Division on the coast immediately to the north, and the 156th Division on the

coast immediately to the south. Also in place and prepared to launch a

counter-attack against our Eastern force were the Japanese 25th and 77th

Divisions. Awaiting the south eastern attack force at Ariake Bay was the

entire Japanese 86th Division, and at least one independent mixed infantry

brigade. On the western shores of Kyushu, the Marines would face the most brutal

opposition. Along the invasion beaches would be the 146th, 206th and 303rd

Japanese Divisions, along with the 6th Tank Brigade, the 125th Mixed Infantry

Brigade and the 4th Artillery Command. Additionally, components of the 25th and

77th Divisions would also be poised to launch counterattacks. If not needed to

reinforce the primary landing beaches, the American Reserve Force would be

landed at the base of Kagoshima Bay on November 4th, where they would be

immediately confronted by two mixed infantry brigades, parts of two infantry

divisions and thousands of the naval landing forces who had undergone combat

training to support ground troops in defence. All along the invasion beaches,

our troops would face coastal batteries, anti-landing obstacles, and an

elaborate network of heavily fortified pillboxes, bunkers, strong points and

underground fortresses.

As our soldiers waded ashore, they would do so through intense artillery and

mortar fire from pre-registered batteries as they worked their way through

tetrahedral and barbed wired entanglements so arranged to funnel them into the

muzzle of these Japanese guns. On the beaches and beyond would be hundreds of

Japanese machine gun positions, beach mines, booby traps, trip-wire mines, and

sniper units. Suicide units concealed in spider holes would meet the troops as

they passed nearby. Just past the beaches and the sea walls would be hundreds of

barricades, trail blocks and concealed strong points. In the heat of battle,

Japanese special infiltration units would be sent to reap havoc in the American

lines by cutting phone and communication lines, and by indiscriminately firing

at our troops attempting to establish a beachhead. some of the troops would be

in American uniform to confuse our troops and English speaking Japanese officers

were assigned to break in on American radio traffic to call off American

artillery fire, to order retreats and to further confuse our troops. Still other

infiltrators with demolition charges strapped on their chests or backs would

attempt to blow up American tanks, artillery pieces and ammunition stores as

they were unloaded ashore.

Beyond the beaches were large artillery pieces situated at key points to bring

down a devastating curtain of fire on the avenues of approach along the beach.

Some of these large guns were mounted on railroad tracks running in and out of

caves where they were protected by concrete and steel. The battle for Japan,

itself, would be won by what General Simon Bolivar Buckner had called on Okinawa

"Prairie Dog Warfare." this type of fighting was almost unknown to the ground

troops in Europe and the Mediterranean. It was peculiar only to the American

soldiers and marines whose responsibility it had been to fight and destroy the

Japanese on islands all over the south and central Pacific. "Prairie Dog

Warfare" had been the story of Tarawa, of Saipan, of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

"Prairie Dog Warfare" was a battle for yards, feet and sometimes even inches. It

was a brutal, deadly and dangerous form of combat aimed at an underground,

heavily fortified, non-retreating enemy. "Prairie Dog Warfare" would be what the

invasion of Japan was all about. In the mountains behind the beaches were

elaborate underground networks of caves, bunkers, command posts and hospitals

connected by miles of tunnels with dozens of separate entrances and exits. Some

of these complexes could hold up to 1,000 enemy troops. A number of these

caves were equipped with large steel doors that slid open to allow artillery

fire and then would snap shut again.

The paths leading up to these underground fortresses were honeycombed with

defensive positions, and all but a few of the trails would be booby-trapped.

along these manned defensive positions would be machine gun nests and aircraft

and naval guns converted for anti-invasion fire. In addition to the use of

poison gas and bacteriological warfare (which the Japanese had experimented

with), the most frightening of all was the prospect of meeting an entire

civilian population that had been mobilized to meet our troops on the beaches.

Had "Olympic" come about, the Japanese civilian population inflamed by a

national slogan. "One Hundred Million will die for the Emperor and Nation", was

prepared to engage and fight the American invaders to the death. Twenty-eight

million Japanese had become a part of the "National Volunteer Combat Force" and

had undergone training in the techniques of beach defence and guerrilla warfare.

These civilians were armed with ancient rifles, lunge mines, satchel charges,

Molotov cocktails and one-shot black powder mortars. Still others were armed

with swords, long bows, axes and bamboo spears.

These special civilian units were to be tactically employed in night time

attacks, hit and run manoeuvers, delaying actions and massive suicide charges

at the weaker American positions. Even without the utilization of Japanese

civilians in direct combat, the Japanese and American casualties during the

campaign for Kyushu would have been staggering. At the early stage of the

invasion, 1,000 Japanese and American soldiers would be dying every hour. The

long and difficult task of conquering Kyushu would have made casualties on both

sides enormous and one can only guess at how monumental the casualty figures

would have been had the Americans had to repeat their invasion a second time

when they landed at heavily fortified and defended Tokyo Plain the following

March. The invasion of Japan never became a reality because on August 6,

1945, the entire nature of war changed when the first atomic bomb was exploded

over Hiroshima. On August 9, 1945, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and

within days the war with Japan was at a close. Had these bombs not been dropped

and had the invasion been launched as scheduled, it is hard not to speculate as

to the cost. Thousands of Japanese suicide sailors and airmen would have died in

fiery deaths in the defence of their homeland. Thousands of American sailors and

airmen defending against these attacks would also have been killed with many

more wounded.

On the Japanese home islands, the combat casualties would have been at a minimum

in the tens of thousands. Every foot of Japanese soil would have been paid for,

twice over, by both Japanese and American lives. One can only guess at how

many civilians would have committed suicide in their homes or in futile mass

military attacks. In retrospect, the one million American men who were to

be the casualties of the invasion, were instead lucky enough to survive the war,

safe and unharmed. Intelligence studies and realistic military estimates made

over forty years ago, and not latter day speculation, show quite clearly that

the battle for Japan might well have resulted in the biggest blood bath in the

history of modern warfare. At best, the invasion of Japan would have

resulted in a long and bloody siege. At worst, it could have been a battle of

extermination between two different civilizations. Far worse would be what

might have happened to Japan as a nation and as a culture. When the invasion

came, it would have come after several additional months of the continued

fire-bombings on all of the remaining Japanese cities and population centres.

The cost in human life that resulted from the two atomic blasts would be small

in comparison to the total number of Japanese lives that would have been lost by

this continued aerial devastation.

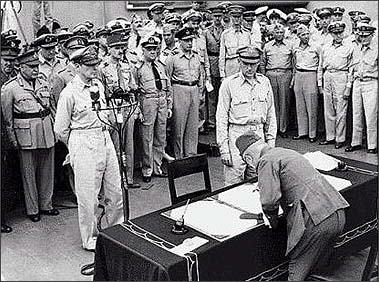

The Atomic Bomb and the Enola Gay

If the invasion had come in the fall of 1945, with the American forces locked in

combat in the south of Japan, who or what could have prevented the Red Army from

marching into the northern half of the Japanese home islands. If "Downfall" had

been an operational necessity, the existence of a separate North and South Japan

might be a modern-day reality. Japan today could be divided down its middle much

like Korea and German. The world was spared the cost of "Downfall" however,

because on September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered to the United Nations

and World War II was finally over. Almost immediately, American soldiers,

sailors, airmen and marines in for the duration were now discharged. The

aircraft carriers, cruisers, transport ships and LST's scheduled to carry our

invasion troops to Japan, now ferried home American troops in a gigantic

troop-lift called "Magic Carpet." The soldiers and marines who had been

committed to invade Japan were now returned home where they were welcomed back

to American shores. All over America celebrations were held and families

everywhere gathered in thanksgiving to honour these soldiers who had been

miraculously spared from further combat and were now safely returning home.

In the fall of 1945, with the war now over, few Americans would ever learn of

the elaborate top-secret plans that had been prepared in detail for the invasion

of Japan. Those few military leaders who had known the details of "Operation

Downfall" were now preoccupied with demobilization and other post war matters,

and were no longer concerned with this invasion that never came. In the

autumn of 1945, in the aftermath of the two thermonuclear explosions that

triggered the Japanese surrender, and with the war a fading memory, few people

concerned themselves with the invasion plans for Japan that had been rendered

obsolete by the atomic age. Following the surrender, the classified documents,

maps, diagrams and appendices for "Operation Downfall" were packed away in boxes

where they began their long circuitous route to the National Archives where they

still remain. But even now more that forty years later, these plans that

called for the invasion of Japan paint a vivid description of what might have

been one of the most horrible campaigns in the history of modern man. The fact

that "Operation downfall", the story of the invasion of Japan, is locked up in

our Nations Archives and is not reflected in our history books is something for

which all Americans can be thankful.

Post Script

With the capture of Okinawa during the summer of 1945

the Americans in the Pacific had finally obtained what the allies in Europe had

enjoyed all along---a large island capable of being used as a launching platform

for invasion. Following the cessation of hostilities with German, millions of

American soldiers, sailors and airmen were being re-deployed to the Pacific for

the anticipated invasion of Japan. The centre of this immense military build up

and the primary staging area for the invasion was the island of Okinawa.

American military planners knew that the invasion of Japan would be a difficult

military undertaking. Japan had never been successfully invaded in its history.

Six and on-half centuries before, an invasion similar to the planned American

invasion had been attempted and failed. That invasion had striking similarities

to the one being planned by the Americans that summer of 1945. In the year

1281 AD two magnificent Chinese fleets set sail for the Empire of Japan. Their

purpose was to launch a massive invasion on the Japanese home islands and to

conquer Japan in the name of the Great Mongol Emperor, Kublai Khan.

Sailing from China was the main armada, consisting of 3,500 ships and over

100,000 heavily armed troops. Sailing from ports in Korea was a second

impressive fleet of 900 ships, containing 42,000 Mongol warriors.

In the summer of that year, the invasion force sailing from Korea arrived off

the western shores of the southernmost Japanese island of Kyushu. The Mongols

manoeuvered their ships into position and methodically launched their assault on

the Japanese coast. Like human surf, wave after wave of these oriental soldiers

swept ashore at Hagata Bay, where they were met on the beaches by thousands of

Japanese defenders who had never had their homeland successfully invaded.

The Mongol invasion force was a modern army, and its arsenal of weapons was far

superior to that of the Japanese. Its soldiers were equipped with poisoned

arrows, maces, iron swords, metal javelins and even gunpowder. The Japanese were

forced to defend themselves with bow and arrows, swords, spears made from bamboo

and shields made only of wood. The battle was fierce with many solders

killed or wounded on both sides. It raged on for days, but aided by the

fortifications along their beaches of which the Mongols had no advance

knowledge; and inspired by the sacred cause of the defence of their homeland,

these ancient Japanese warriors pushed the much stronger Mongol invaders off the

beaches and back into their ships lying at anchor in the Bay.

This Mongol fleet then set back out to sea, where it rendezvoused with the main

body of its army, which was arriving with the second fleet coming from China.

During the summer of 1281, this combined force of foreign invaders manoeuvered

off shore in preparation for the main assault on the western shores of Kyushu.

All over Japan elaborate Shinto ceremonies were performed at shrines, in the

cities, and in the countryside. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese urged on by

their Emperor, their warlords, and other officials prayed to their Shinto gods

for deliverance from these foreign invaders. A million Japanese voices called

upward for divine intervention. Miraculously, as if in answer to their prayers,

from out of the south a savage typhoon sprang up and headed toward Kyushu. Its

powerful winds screamed up the coast where they struck the Mongol's invasion

fleet with full fury, wreaking havoc on the ships and on the men onboard. The

Mongol fleet was devastated. After the typhoon had passed, over 4,000 invasion

craft had been lost and the Mongol casualties exceeded 100,000 men. All over

Japan religious services and huge celebrations were held. Everywhere tumultuous

crowds gathered in thanksgiving to pay homage to the "divine wind" that had

saved their homeland from foreign invasion. At no time thereafter has Japan ever

been successfully invaded. The Japanese fervently believed that it was this

"divine wind" that would forever protect them.

During the summer of 1945 another powerful armada was being assembled to assault

the same western coastline on the island of Kyushu, where six and one-half

centuries earlier the Mongols had been repelled. The American invasion plans for

Kyushu, scheduled for November 1, 1945 called for a floating invasion force of

14 army and marine divisions to be transported by ship to hit the western,

eastern and southern shoreline of Kyushu. This shipboard invasion forced would

consist of 550,000 combat soldiers, tens of thousands of sailors and hundreds of

naval aviators. The assault fleet would consist of thousands of ships of

every shape, size and description, ranging from the mammoth battleships and

aircraft carriers to the small amphibious craft, and they would be sailing from

Okinawa, the Philippines and the Marianas. Crucial to the success of the

invasion were nearly 4,000 army, navy, and marine aircraft that would be packed

into the small island of Okinawa to be used for direct air support of our

landing forces at the time of this invasion. By July of 1945, the Japanese

knew the Americans were planning to invade their homeland. Throughout the early

summer, the Emperor and his government officials exhorted the military and

civilian population to make preparations for the invasion.

Okinawa

Japanese radios throughout that summer cried out to the people to "form a wall

of human flesh" and when the invasion began, to push the invaders back into the

sea, and back onto their ships. The Japanese people fervently believed

that the American invaders would be repelled. They all seemed to share a

mystical faith that their country could never be invaded successfully and that

they, again, would be saved by the "divine wind". The American invasion never

came, however, because the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as if by a

miracle, ended the war. Almost immediately American soldiers, sailors, and

airmen, in for the duration, were being discharged and sent home. By the autumn of

1945, there remained approximately 200,000 soldiers, sailors and airmen still on

Okinawa. Okinawa, which would have been the major launching platform for the

invasion of Japan, was now peaceful. In October, Buckner Bay, on the east coast

of the island, was still jammed with vessels of all kinds---from Victory ships

to landing craft. On the island itself, 150,000 soldiers lived under miles of

canvas, in what were referred to as "Tent Cities." All over the island, hundreds

of tons of food, equipment and supplies stacked in immense piles lay out in the

open.

Northern Mariannas

During the early part of October, to the southwest of Okinawa just northeast of

the Marianas, the seas were growing restless and the winds began to blow. The

ocean skies slowly turned black and the large swells that were developing began

to turn the Pacific Ocean white with froth. In a matter of only a few days, a

gigantic typhoon had somehow, out of season, sprung to life and began sweeping

past Saipan and into the Philippine Sea. As the storm grew more violent, it

raced northward and kicked up waves 60 feet high. Navy Meteorologists eventually

became aware of the storm, but they expected it to pass well between Formosa and

Okinawa, and to disappear into the East China Sea. Unexplainable, on the evening

of October 8th, the storm changed direction and abruptly veered to the east.

When it did so, there was insufficient warning to allow the ships in the harbour

to get under way in order to escape the typhoon's terrible violence. By late

morning on the 9th, rain was coming down in torrents, the seas were rising and

visibility was zero. Winds, now over 80 miles per hour blowing from the east and

northeast, caused small crafts in Buckner Bay to drag their anchors. By early

afternoon, the wind had risen to over 100 miles per hour, the rain coming in

horizontally now was more salt than fresh, and even the larger vessels began

dragging anchor under the pounding of 50 foot seas. As the winds continued to

increase and the storm unleashed its fury, the entire Bay became a scene of

devastation. Ships dragging their anchors collided with one another; hundreds of

vessels were blown ashore. Vessels in groups of two's and three's were washed

ashore into masses of wreckage that began to accumulate on the beaches.

Numerous ships had to be abandoned, while their crews were precariously

transferred between ships. By mid-afternoon, the typhoon had reached its raging

peak with winds, now coming from the north and the northeast, blowing up to 150

miles per hour. Ships initially grounded by the storm were now blown off the

reefs and back across the bay to the south shore, dragging their anchors the

entire way. More collisions occurred between wind-blown ships and shattered

hulks. Gigantic waves swamped small vessels and engulfed larger ones. Liberty

ships lost their propellers, while men in transports, destroyers and Victory

ships were swept off the decks by 60 foot waves that reached the tops of the

masts of their vessels. On shore, the typhoon was devastating the island. Twenty

hours of torrential rain washed out roads and ruined the island's stores of

rations and supplies. Aircraft was picked up and catapulted off the airfields;

huge Quonset huts were sailing into the air, metal hangars were ripped to shreds

and the "Tent Cities", housing 150,000 troops on the island, ceased to exist.

Almost the entire food supply on the island was blown away. Americans on the

island had nowhere to go, but into the caves, trenches and ditches of the island

in order to survive. All over the island there were tents, boards and sections

of galvanized iron being hurled through the air at over 100 mph. The storm raged

over the island for hours, and then slowly headed out to sea; then it doubled

back, and two days later howled in from the ocean to hit the island again. On

the following day, when the typhoon had finally past, dazed men crawled out of

holes and caves to count the losses.

Countless aircraft had been destroyed, all power was gone, communications and

supplies were nonexistent. B-29's were requisitioned to rush in tons of rations

and supplies from the Marianas. General Joseph Stillwell, the 10th Army

Commander, asked for immediate plans to evacuate all hospital cases from the

island. The harbour facilities were useless. After the typhoon roared out into

the Sea of Japan and started to die its slow death, the bodies began to wash

ashore. The toll on ships was staggering. Almost 270 ships were sunk, grounded

or damaged beyond repair. Fifty-Three ships in too bad a state to be restored to

duty were decommissioned, stripped and abandoned. Out of 90 ships which needed

major repair, the Navy decided only 10 were even worthy of complete salvage, and

so the remaining 80 were scrapped. According to Samuel Eliot Morrison, the

famous Naval historian, "Typhoon Louise" was the most furious and lethal storm

ever encountered by the United States Navy in its entire history. Hundreds of

Americans were killed, injured and missing, ships were sunk and the island of

Okinawa was in havoc. News accounts at the time disclose that the press and the

public back home paid little attention to this storm that struck the Pacific

with such force. The very existence of this storm is still a little-known fact.

Surprisingly, few people then, or even now, have made the connection that an

American invasion fleet of thousands of ships, planes and landing craft, and a

half million men might well have been in that exact place at that exact time,

poised to strike Japan, when this typhoon enveloped Okinawa and its surrounding

seas.

In the aftermath of this storm, with the war now

history, few people concerned themselves with the obsolete invasion plans

for Japan. However, had there been no bomb dropped or had it been simply

delayed for only a matter of months, history might well have repeated

itself. In the fall of 1945, in the aftermath of this typhoon, had things

been different, all over Japan religious services and huge celebrations

would have been held. A million Japanese voices would have been raised

upward in thanksgiving. Everywhere tumultuous crowds would have gathered

in delirious gratitude to pay homage to a "divine wind" which might have

once again protected their country from foreign invaders, a "divine wind"

they had names, centuries before, the "Kamikaze."

http://sandysq.gcinet.net/uss_salt_lake_city_ca25/topsecrt.htm

Footnote. From an email received January 2005:

My father was a US Marine serving

on the island of Guam on the last day of WW2. He was guarding a top secret

warehouse with the divisions invasion supplies in it. There were a dozen marines

around the sealed up warehouse at all times with shoot to kill orders. Anyone

get's near the warehouse is to be shot. These marines were stuck out there while

the entire island got drunk. About 2 AM they saw the lights of a jeep coming

towards them. The jeep contained the senior officers in the division and there

was a Major so drunk that he was draped across the hood with officers in the

front seat holding onto him. When they pulled up they got out and proceeded to

shake and slap the major awake. They thrust a clip board and keys into his

hands. The Major then walked over and secured the guards. The Major walked over