The Loss of The Mighty Hood

|

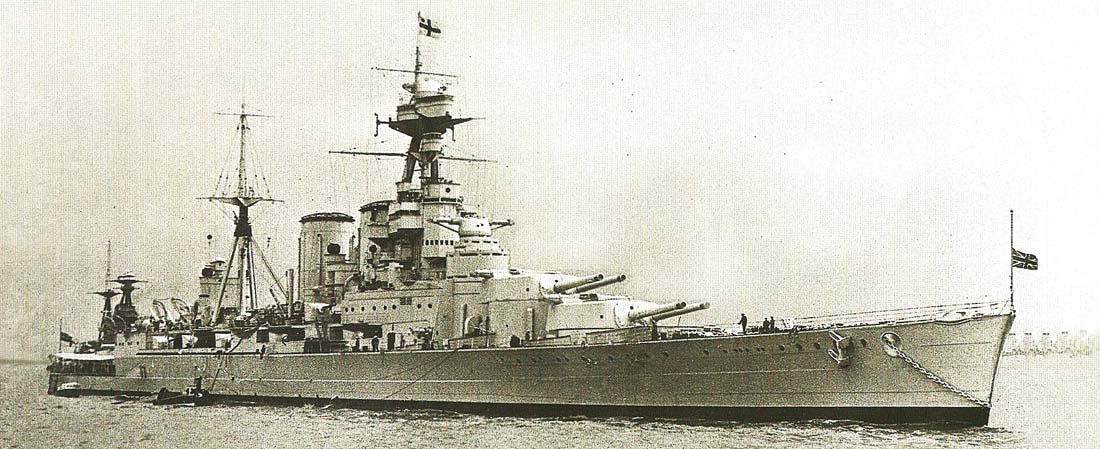

HMS Hood was launched on 22 August 1918, then spent 2 years being fitted out. She was commissioned on 15th May 1920. Popularly known as 'The Mighty Hood' she was launched as the largest warship in the world, a symbol of British Imperial power. Classified as a battlecruiser. HMS Hood was actually a fast battleship and built to the highest specifications, a massively armed warship with armour considered to be the equal of her armaments. In the inter war years, Hood was part of a famous world cruise with fellow battlecruiser, HMS Repulse, which saw them go the the far east, the Pacific and USA. When she returned to the UK she was modernised, twice, during the Spanish Civil War HMS Hood took part in an international force that intervened to deliver food to the besieged population of Bilbao. By the outbreak of WW2, Hood was ready for a major refit, having been on active service around the world. Her magazines were known to be vulnerable, especially from long range when incoming shells would be travelling fast, at more acute angles. The refit never came. The killing shot was almost certainly a shell into the magazine, but some speculate fire caused the explosion.

On the outbreak of World War 2, Hood took part in the chase of German warships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and then helped escort convoys across the Atlantic. In 1940, after Germany had successfully invaded France, Hood became part of Force H, operating from Gibraltar, helping to defend the Western end of the Mediterranean. After seeing action in the Med, Hood, along with Prince of Wales, was ordered to intercept the Bismarck, it was imperative she was stopped. Hood, faster than the Bismarck, caught up with the German ship to the west of Iceland, in the Demark Strait on the morning of the 24th May 1941. Just before 0600 hrs, both ships opened fire. Hood was quickly hit, setting her alight, which spread to the magazines. The resulting explosion tore the mighty ship apart and she immediately sank with only 3 sailors making it into the sea out of 1418 crew. The loss of the Hood, under such circumstances, caused a massive shock wave to reverberate throughout Britain. Churchill was furious and sent his now famous signal to the Royal Naval Fleet 'the Bismarck must be sunk at all costs' - and here began one of the most dramatic chases in the history of naval warfare.

She was the longest Royal Naval ship ever built.

Although she was classified as a Battle Cruiser, Hood was a fast battleship, an

improved version of the Queen Elizabeth Class. With the same main armament of 8

x 381mm guns, a higher position for the secondary armament, sloped armour belt

and improved torpedo protection, she included the latest ideas of naval

construction in 1915. The speed requirement meant a very long hull was

essential. HMS Hood was the longest ship built for the Royal Navy ever.

On the outbreak of war HMS Hood was at Scapa Flow with the Home Fleet. In June 1940 she was allocated to Force H, in the Mediterranean. Force H’s first task was its most distasteful, to neutralise the French squadron at Oran in Algeria. At 1755hrs on 3rd July 1940 Hood and her compatriots opened fire; the battleship Bretagne was blown up and the Provence and Dunkerque badly damaged. Hood returned to the Home Fleet and on 19th May 1941 she sailed with the brand new battleship Prince of Wales to intercept the German battleship Bismarck that was attempting to break out into the North Atlantic. Bismarck, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, was shadowed on radar by the Norfolk and Suffolk which reported their position to HMS Hood. In the Denmark Strait on the morning of 24th May Admiral Holland ordered his ships to close the range and shortly before 0600hrs both sides opened fire. The Bismarck’s fifth salvo hit the Hood amidships penetrating the secondary armament magazine. The detonation spread to the main magazine resulting in a catastrophic explosion which tore the ship in half. Only three of her 1418 crew survived.

When the Bismarck was launched on 14 February 1939, she was the first of the new breed of ships that Hitler and Grand Admiral Raeder hoped would herald the rebirth of the German surface battle fleet. Although listed as 35,000 tons to ensure that she fell within the limits of the London Naval Treaty, Bismarck did, in fact, displace well over that. She was actually of comparable size and main armament to the largest British warship of that time, H.M.S. Hood. Despite the similarities, there were differences between the two ships: Bismarck was a modern battleship in the truest sense. Her critical spaces were well protected by excellent internal compartments and high quality heavy armour. She also boasted the latest electronics plus very accurate and rapid firing gunnery systems. She and her sister Tirpitz were arguably among the best ships at that time. By comparison, Hood was well-built for her day (1920), but by 1941 was arguably an aged battle cruiser. She had adequate protection in some key areas, but not all. Because of her machinery, she was filled with large, somewhat open spaces. Though her speed had been reduced over the years, at 29 knots, she was still fast for her size. Her guns were deadly, but she had outdated gunnery systems. She did boast advanced radar, but her crew had hardly enough time to become proficient in its use. To fight each other, Bismarck could absorb more damage while firing faster and more accurately than Hood. Bismarck could take AND give more in battle. Each ship had the ability to sink or severely damage the other, but the advantage clearly was with Bismarck. This is not a negative reflection on Hood, but simply an observance that Bismarck was 20 years more modern than Hood. Bismarck's design reflected all that had been learned between the times the two ships were built. Hood, Prince of Wales and destroyers, weighed anchor at 2356 hrs. They departed Scapa Flow at midnight, 22nd May, heading for Hvalsfjord. Shortly thereafter, the destroyers were divided into two divisions - one to screen Hood and the other to screen Prince of Wales. The vessels then commenced zigzagging and steered 310º. This continued until 1855 hours, when the course was altered to 283º. By noon, 23 May, the vessels were at 62º 55' N 02º 14.8' W and on a heading of 270º. Shortly thereafter, another successful RIX was conducted. At 1400 hours, the destroyers Anthony and Antelope, short on fuel, parted company with the force and headed for Iceland. As the day wore on for the remaining vessels, the weather grew cloudy and the sea swells became heavier. Back at Scapa Flow, Tovey was now faced with a decision about whether to sail himself so when Tovey at last found out for certain that the German ships were no longer at Bergen, he still had the uncertainty about enemy intentions remaining. Lütjens's force had in fact sailed from Bergen during the early evening of 21st May. The poor weather conditions had been perfect for an undetected departure. At roughly 1915 hrs 23rd May, Able Seaman Newell on board the cruiser HMS Suffolk, in the Denmark Straits, was on duty as the starboard after look out. He was there to cover the 'blind' zone in Suffolk's radar coverage astern. As he scanned the horizon he saw Bismarck, and then Prinz Eugen roughly 7 miles away. He immediately called out 'Ship bearing green one four oh', followed seconds later by 'two ships bearing green one four oh'. Suffolk heeled over to port to seek the cover of the fog bank. It was also probable that Bismarck had not spotted Suffolk as she did not open fire. Signals were sent out to say that contact with the enemy had at last been made. By 2000 hrs, Hood's force was at 63º20N' 27º00'W. Shortly before this, at 1939 hrs, Vice-Admiral Holland ordered his vessels to raise steam for full speed and to change course to 295º. Shortly thereafter, at 2004 hrs, he had the news he had been waiting for: Suffolk had positively sighted Bismarck and its consort in the Denmark Strait. This was followed-up by a report from Norfolk at 2040 hrs. Plots put the Germans approximately 300 miles to the north of Holland’s force. Vice Admiral Holland had possibly tow choices. The first option was to cut across their bows on a westward course whilst they headed south. This would allow all the British guns to bear on the German ships whilst the enemy would only be able to fire at the British squadron with their forward guns. Of course, such a move could be easily countered. The second choice was for Holland's ships to cross the German squadrons path well ahead, then swing around and approach from the west. This would silhouette the Germans against the morning sky and considerably ease range finding for the British. By 2054 hrs, HMS Hood was steaming at 27 knots on a heading of 295º. As the speed increased, the destroyers were struggling to maintain station in the heavy seas. Vice-Admiral Holland signalled to the destroyers 'If you are unable to maintain this speed, I will have to go on without you. You should follow at your best speed'. The four tiny destroyers did their best to keep up with the old battle cruiser fairly but took a horrendous buffeting in doing so. At 2200 hrs, the crews of Hood, Prince of Wales and their accompanying destroyers were officially notified of the Germans presence in the Denmark Strait. Interception and anticipated action would take place between 0140 and 0200 hours that morning. All hands were ordered to be prepared to change into clean undergarments (to help prevent infection should they be wounded) and to don battle gear (life vests, flash gear, gas masks, helmets and, where necessary, cold weather gear). At 2230 hrs, 'darken ship' was ordered. By 0015 hours, 24 May, crews aboard both ships had been called to action stations and the battle ensigns were raised. They were then an estimated 120 miles south of the German ships. So it was that shortly after midnight, HMS Suffolk reported that she had lost radar contact with the German vessels. Aboard HMS Hood, Vice-Admiral Holland calmly received the news. With no definite position for the German warships, he ordered that the crews to go to relaxed action stations (permission to sleep or at least relax at action stations) and a reduction in the ships’ speed to 25 knots. The heading changed to the north (340º) in order to cover any possible reversal of course by the Germans. And so by now it was a guessing game for the British forces. Loss of contact by Suffolk was a blow and suggested that the German squadron may well have altered course. This being the case, he had to decide what that course alteration might be. They may have decided that having been tracked it was likely that British forces would be concentrated to intercept them, and that it would be better to reverse course and disappear into the Arctic Ocean. Alternatively, they may have altered course to the south-east or the south-west. In any case, it seemed to Holland that the best course of action was to close the distance between his ships and the last known position of the German squadron as quickly as possible at this point. He signalled to his force at 0030 hrs that 'If enemy is not in sight by 0210, I will probably alter course 180º until cruisers regain touch'. He then once again signalled his battle plan: 'Intend both ships to engage Bismarck and to leave Prinz Eugen to Norfolk and Suffolk'. Of course, due to the ban on radio usage, this message was not transmitted to either Suffolk or Norfolk. At 0147 hrs, Holland signalled 'If battle cruisers turn 200º at 0205 destroyers continue to search to the northward'. Due to the poor weather and restricted visibility, it is not known if all four destroyers received the order. This order shows the extent to which, just a few hours before the engagement took place, the British forces were 'searching in the dark'. At 0203 hrs, just after dawn (approximately 0200 hrs in those latitudes at that time of year), Hood and Prince of Wales assumed a more southerly course of 200º at a speed of 25 knots. The destroyers then parted with the large ships to screen at 15 mile intervals to the north. This was to better the chances of locating the Germans should they successfully elude the Suffolk and Norfolk. Holland also ordered Prince of Wales to use her Type 284 gunnery radar to search 020 - 140º. Unfortunately, Prince of Wales's Type 284 radar was experiencing troubles which rendered it more or less defective. Captain Leach therefore requested permission to use the somewhat more powerful Type 281 radar, but his request was refused, as the transmissions/emissions would have caused great interference to Hood's own Type 284 radar. At 0247 hrs, Suffolk regained radar contact with the fleeing German vessels. Her reports placed the Germans approximately 35 miles/64.8 km north-west of Hood and Prince of Wales. Holland ordered another heading change, this time to 220º. Speed was gradually increased to 28 knots. By 0341 hrs, both vessels were on a course of 240º. At 0450 hrs, Prince of Wales took over guide of the fleet, positioning herself ahead of Hood. Why this temporary switching of position took place is not clear. It is recorded in Prince of Wales's log as well as in the narrative of the operation written afterwards by Captain Leach but neither document explains the reason behind the move. Hood resumed guide at 0505 hrs. Between 0500 and 0510 hrs, Holland quietly ordered, 'Prepare for instant action'. The crews then went to the first level of readiness. The command crew trained their binoculars and strained their eyes to the north, as they silently waited for contact to be made. Over the past few hours the sky had grown lighter and visibility gradually increased, so that at roughly 0535 - 0536 hrs, lookouts in Prince of Wales visually sighted smoke and mast tops of the enemy vessels at a range of at least 38,000 yards (18.75 nm). By 0537 hrs enough of the ships could be seen to confirm they were the Germans. Prince of Wales transmitted an enemy report at 0537 hrs. Translated from code, it read: 'Emergency to Admiralty and C in C Home Fleet. One battleship and one heavy cruiser, bearing 335, distance 17 miles. My position 63 - 20 North, 31-50 West. My course 240. Speed 28 knots'. Hood sighted the Germans shortly thereafter, but did not transmit her enemy report until 0543 hours. The Germans were well aware of the approach of the British warships, hydrophones aboard Prinz Eugen had detected the sounds of fast moving turbine-driven vessels some time earlier in the hour. The initial assumption was that they were cruisers. Spotters in Prinz Eugen and Bismarck first sighted the smoke plumes of the approaching British vessels around 0535 hrs. At 0537 hrs, they intercepted Prince of Wales's enemy report. Despite this, they apparently were not yet aware that they were being intercepted by major warships. An intercept of any kind was not apparent until 0543, when Hood was sighted and her enemy report intercepted. Though the foes were still thought to be cruisers, the alarm was ordered in both German ships. After the alarm at 0545hrs, the German crews, like their British counterparts, prepared themselves and anxiously awaited orders. These, however, were not soon to come, Admiral Lütjens was in somewhat of a quandary, as he had strict orders not to engage enemy warships unless absolutely necessary. His main priority was to get out into the Atlantic unscathed. If he took the time to engage the approaching vessels, it may delay him sufficiently to allow other British warships to join the fray. Worse, he could sustain damage or lose one or even both of his ships. He took no apparent action other than to order a possible increase in speed by Bismarck. At 0537 hrs, Vice-Admiral Holland had ordered his vessels to turn 40º to starboard together. This put the vessels on a heading of 280º, and placed the enemy fine off Hood and Prince of Wales's bows. The British ships were steaming at nearly 29 knots, with Prince of Wales roughly 800 yards off Hood's starboard quarter. Unfortunately, rather than come out ahead of the Germans, Holland's force had actually been on a diverging course. Now that his original intentions were no longer possible, Holland's plan was to make a head-on dash at the enemy, then turn at short range to bring his full guns to bear. Holland had a possible reason for doing this: First, he may have been considering Hood’s susceptibility to long range, high velocity, plunging shells: her weak deck armour and some areas of her side armour could easily be penetrated with disastrous results. It was critical that HMS Hood closed the range as quickly as possible but without allowing the Germans to slip ahead of his ships. Once the range had been closed, Hood would still be susceptible to enemy fire, but fire at such ranges would come at flatter trajectories. Hood's main side armour during such an engagement should hopefully stand up to enemy gunfire. He may have merely been trying to present an end-on and smaller target until he was within ranges more suited to accurate gunnery for Hood. There were still some risks and major disadvantages to the approach he had in mind however, by approaching virtually head-on, the British ships would not be able to bring their full compliment of main guns (8 x 15" for Hood and 10 x 14" for Prince of Wales) to bear. The ships would also be charging into the wind, the spray would make using their optical range finders difficult. Holland also had his ships in close formation. If the enemy did find the range, it would be fairly easy to shift fire from one ship to the other. Lastly, as the ships raced towards each other, the Germans would still have the advantage of bringing full guns (8 x 15" for Bismarck and 8 x 8" for Prinz Eugen) to bear. Their optical equipment (already far superior to the British types) would also suffer less from the effects of the wind and spray, as the wind would be on their other sides. Lastly, if the ship were not perfectly end-on, it would actually present the German gunners with a large target.

Action commenced at 0552 1/2 hours, as Hood's two forward turrets fired the first salvoes. Half a minute later, Prince of Wales's forward turrets followed suit. Hood's first salvo fell near Prinz Eugen but did not actually hit. Prince of Wales's opening salvo was observed to be at least 1,500 yards over and to the right of Bismarck. The Germans were shocked to learn that the approaching vessels were not cruisers – they were in fact major combatants – a King George V class battleship and even worse, the famed and feared battle cruiser H.M.S. Hood. At 0555 hrs, after about two minutes of British shelling, Captain Lindemann then give permission to open fire. Bismarck, firing four gun salvoes, shot first followed shortly by Prinz Eugen. Both vessels concentrated their fire on the lead British vessel, Hood. Bismarck’s first salvo fell in front and slightly to starboard of Hood. Bismarck’s second, fell directly between Hood and Prince of Wales. Its third salvo appeared to straddle Hood. Meanwhile, Prinz Eugen had loosed between 2 and 3 salvoes herself. One of these salvoes straddled Hood at roughly the same time that Bismarck's third salvo fell. A hit on Hood from Prinz Eugen started a bright fire that proceeded to spread across a portion of the shelter deck to port of the main mast and aft superstructure. Though it apparently did not reach the motor launches/boats, it did reach various ready-use ammunition lockers and began 'cooking off' the munitions inside. Vice-Admiral Holland realised that the situation was getting desperate: The Germans had already found the range and HMS Hood was taking hits. He was also suffering casualties on the burning shelter deck. Neither of his own ships appeared to be scoring any decisive hits on the enemy. Hood, having made the error of opening fire against the wrong ship was only now getting the correct range for Bismarck. At 0555 hours both ships turned to port to open up firing from their rear turrets. Sometime during the first moments of the execution of this turn, Hood was dealt her death blow, Bismarck's 5th salvo had straddled, with one or two shells likely striking Hood somewhere around the main mast, or possibly through a narrow weak zone in her side. Aboard Prince of Wales, Captain Leach happened to be looking at Hood: "...at the moment when a salvo arrived and it appeared to be across the ship somewhere about the mainmast. In that salvo there were, I think, two shots short and one over, but it may have been the other way round. But I formed the impression at the time that something had arrived on board Hood in a position just before the mainmast and slightly starboard. It was not a very definite impression that I had, but it was sufficiently definite to make me look at Hood for a further period. In fact I wondered what the result was going to be, and between one and two seconds after I formed that impression, an explosion took place in the Hood, which appeared to me to come from very much the same position in the ship. There was a very fierce upward rush of flame the shape of a funnel, rather a thin funnel, and almost instantaneously the ship was enveloped in smoke from one end to the other.'

The official HMS Hood web site states that “although there was naturally some variation in the reports that witnesses gave, most agree that a tall, slim geyser of flame, similar in appearance to a welding torch, shot up from the area around the main mast (possibly venting flame/gas shooting up from the engine room vents). At the same time, a gigantic, strangely quiet, explosion or conflagration wracked the entire aft end of the ship. Large pieces of debris were observed in the air. As the flames turned into a mushroom cloud, the entire ship became wreathed in heavy smoke. She slowed to a stop and heeled heavily to starboard.” On Hood, a bright flash was seen to sweep round outside and everyone was thrown to the floor. The ship momentarily righted herself, then she began an roll to port, a roll from which she never recovered. As she rolled to port, she began to go down by the stern. The bow began to swing sharply upwards, HMS Hood was going down and doing so quickly. In his book Flagship Hood, survivor Ted Briggs records that Vice-Admiral Holland, sat dejectedly in his seat, with Captain Kerr attempting to stand at his side, and that no order was given to abandon ship, it really was not necessary. Everyone seemed to realise what was happening. Those that could do so, very calmly left their stations in an attempt to clear the foundering ship. The 'Mighty Hood', most famous of all warships, had just been devastated by a massive explosion. It truly was unfathomable if not nightmarish to all who watched. This spectacle resulted in a momentary lull in the battle. The section of the ship from just before the main mast aft to "Y" turret was laid waste – a mass of largely unrecognisable steel and twisted framework. Witnesses watched in horror as the remains of the stern, twisted, swung vertical and quickly sank. The front section swung high into the air at an angle between 45º and vertical and began to pivot about as it rapidly sank. According to the Germans, as the bow rose into the air, Hood's forward turrets were seen to fire one last salvo. If this is true, it is likely due to a short or a mechanical failure. Another possibility is that they were venting flames from an internal fire or smaller scale explosion.

Hood was gone. Out of her crew of 1,418 men, only three, Midshipman William Dundas, Able Seaman Robert Tilburn and Signalman Ted Briggs remained. Dundas had escaped the Compass Platform by kicking out one of the starboard windows. He squeezed through to safety just as the sea reached him. Moments earlier, Ted Briggs had exited the Compass Platform by the starboard side door. As Ted reached the door, the Squadron Navigator, Commander Warrand, smiled and selflessly moved aside and gestured for him to leave first. Though he was sure that Commanders Warrand and Gregson had also made it outside, he was never to see either of them again. As Ted climbed down the ladderways, the sea overtook him. He came to the surface a short time later. Meanwhile, on Hood's port forward shelter deck, Able Seaman Bob Tilburn escaped by climbing down onto the fo'c'sle deck and diving into the sea. He narrowly missed being fatally trapped by Hood's plunging superstructure. After being dragged down some distance, he freed himself and reached the surface. There was no trace of the other 1,415 crewmen. Of HMS Hood herself, all that remained on the surface was a morass of floating debris and an oil slick 4" deep. Fire flickered here and there among the debris. They were eventually rescued by HMS Electra and landed in Iceland on May 24th then flown home to the United Kingdom. The first enquiry was convened in early June. They quickly reached the conclusion that one or more shells from Bismarck had managed to penetrate Hood's armour/protective plating and detonate her aft magazines. Although it was a logical conclusion, the proceedings came under scrutiny. As it turned out, very few witnesses were called, and of the Hood survivors, only Dundas gave evidence. Verbatim records of the evidence were not made and to make matters worse, the appropriate experts had not been called. It was not long before the Admiralty decided that a second board would have to be convened.

The second Board convened on 27th August 1941 under the Chairmanship of Rear-Admiral H.T.C. Walker, a former Captain of the Hood. This board called two of the three survivors (Ted Briggs and Bob Tilburn), numerous eyewitnesses from Prince of Wales, Suffolk and Norfolk. It also called experts in the fields of construction and armament/explosives. Although far more thorough than the first enquiry, the second Board ultimately reached much the same conclusions as the first Board – A salvo from Bismarck penetrated Hood's vitals and detonated the aft magazines. Other possibilities exist, but a shell from Bismarck was the most likely cause.

Ted Briggs Story as found on http://www.navynews.co.uk/articles/2002/0207/1002072501.asp As Ted Briggs gulped down oily water deep in the icy seas of the Denmark Strait, he didn’t feel particularly lucky. The young signalman had literally stepped from the bridge of the legendary battle cruiser HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy between the wars, as she rolled and sank, riven by explosions and fires started by shells from the German battleship Bismarck and her consort Prinz Eugen. At first sucked down by the vortex caused by the dying ship, Ted still vividly remembers his struggle for life, and the growing realisation that he would not survive – only to be forced up through the oil-slick on the surface of the sea in time to watch, in horror, the last moments of the mighty Hood. The warship first weaved its magic on Ted in the summer of 1935, when he had gazed in awe at Hood as she lay off a Yorkshire seaside town. “I was 12 years old when I saw her – that still sticks in my mind,” said Ted, now a charming, thoughtful man who looks younger than his 79 years. “I wasn’t really looking to join the Navy before that, but I saw this ship at Redcar beach and I was quite impressed.” Indeed, Ted’s luck was in almost as soon as he joined the Royal Navy, spurred into the service by his attraction to the ship. He trained at HMS Ganges in Suffolk, and his first draft fulfilled his dreams by sending him to join the Hood at Scapa Flow. Sharing a capital ship with 1,420 others came as a shock initially, but by May 24, 1941, when Hood was steaming north in company with HMS Prince of Wales, in search of the German ships Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, Ted felt at home, and in no immediate danger. “There was no sense of anything being wrong with the ship on that day,” said Ted. “We knew two powerful ships were coming, but there was no sense that we were going to get sunk, or pounded, or anything like that.” The two powerful German raiders, aiming to break out into the Atlantic to wreak havoc on convoys, were being shadowed by the cruisers HM ships Norfolk and Suffolk, which guided the British capital ships to their fateful rendezvous. Hood and HMS Prince of Wales had steamed to the area at 29 knots, leaving their destroyer escort some 50 miles in their wake as the smaller ships struggled through heavy seas. As Ted worked as the Flag Lieutenant’s runner on the compass platform, from where the admiral’s staff directed the action, he was privy to the thoughts and plans of Admiral Holland and Captain Kerr, who wanted the two heavy ships to concentrate their fire on the Bismarck while Norfolk and Suffolk engaged the Prinz Eugen. The destroyers were to join the action as soon as possible, firing their torpedoes. But, unknown to the British, the smaller German ship had by that time taken a position ahead of the Bismarck, and as the two ships had similar outlines and the weather was far from clear, the Royal Navy attack was at first directed at Prinz Eugen, and her bigger companion was all but ignored. “Gunnery in the Hood was good, but not as good as Bismarck,” said Ted. “We fired a couple of salvoes at what we thought was the Bismarck before the Prince of Wales said we were firing at the wrong ship and we changed over. At that distance you could only see the superstructures.” “We fired about six salvoes before Bismarck answered – we took her by surprise. She had no idea there were heavy units in the vicinity, because of radio silence. “We had hit her with one which caused a fuel leakage, but it wasn’t all that serious. “When she did reply, her first salvo fell short – you could see the splashes. The next went over and you could hear the roar like a thousand express trains. The third hit the base of the mainmast, causing a fire in the 4in ready-use ammunition lockers. “The Captain said to leave it until the ammunition had been expended, and clear the boat-deck of personnel. That was when Bob (AB Bob Tilburn, of the 4in gun crews on the boat deck) saw what was going on – there was sheer carnage. “In the next salvo one shell took away the spotting top, but didn’t explode. An officer fell on to the bridge wing – the only way we could tell he was an officer was by the rings on his sleeve. He had no face left, and no hands. That shook up Bill Dundas (action midshipman of the watch). “The fifth salvo hit us as we were coming in, bows on, to close the range to 12 miles as quickly as possible. “There was no explosion that I could hear. We were thrown off our feet and I saw a gigantic sheet of flame which shot round the compass platform. The ship started listing to starboard, about 10-12 degrees, then it started to right itself. “The Quartermaster reported that the steering gear had gone, and we were to go to emergency conning, but as we did the ship started going to port, and it kept going. It got to 30-40 degrees and we realised the ship wasn’t coming back. “There was no panic – it’s uncanny, but everything seemed to be in slow motion. We tried to get out of the starboard door. The Gunnery Officer was just in front of me, and the Navigating Officer stood to one side to let me go through. “I had got half-way down the ladder to the admiral’s bridge when we were level with the water. We were just dragged under. I do not know how long it was, but I got to the stage where I just couldn’t hold my breath any more. “It sounds silly but there was a cartoon of Tom and Jerry where Tom is drowning, and he had a blissful smile on his face. I was just like that – a calm acceptance – and then suddenly I shot to the surface. “I came up on the port side, even though I had gone out of

the starboard door – I don’t know how I got there – and I was roughly 50 yards

away from the ship. “I swam away as fast as I could, so that I wouldn’t get sucked down again, and when I looked back the ship had gone, but the oil on the water had caught fire. I panicked and swam away again, but when I looked back again the fire was out.” Ted clambered on to one of the 3ft square rafts that floated in the wreckage-strewn oily water, and spotted Midshipman Bill Dundas, from the compass platform, and AB Bob Tilburn, who had survived the carnage among the 4in gun crews on the boat deck. Both had scrambled on to rafts, which meant that there were just three survivors of the sinking which claimed the lives of 1,418 sailors. “There wasn’t a sign of anyone else – we couldn’t see any bodies or anything,” said Ted. “I think those below decks would not have stood a hope in hell, and those on the upper decks were killed or wounded before the ship went. I just couldn’t grasp it. “We could see the Prince of Wales disappearing, still firing, and when she had gone I could see in the distance the tops of three funnels – one of the cruisers, but I didn’t know which one. And that was it. “I remember Bill Dundas was singing Roll Out the Barrel, like he was conducting a band – he was just keeping his circulation going, because it was bitter cold.” They drifted for nearly four hours in the ocean swell until late morning, when Bill Dundas saw the destroyer HMS Electra making her way towards the three survivors. Once on board Electra, the Hood men were taken down to the mess decks and liberally plied with rum, which had the beneficial effect of making them sick, bringing up some of the oil they had swallowed. They were landed at Reykjavik, and after their initial recovery they went by troopship to Greenock and on by train to London, travelling in some style but not allowed to see or speak to anyone. In London they were ushered in to see Second Sea Lord Admiral Whitworth, Admiral Holland’s predecessor, who recognised Briggs – “I had knocked him on to his bum coming down from the compass platform of the Hood one dark night,” said Ted. “The sinking shook the Royal Navy and everybody else rigid. When it came out, everybody just kept saying they just couldn’t believe it. “She went down at 6.05am on May 24, and it was announced, so I understand, on the six o’clock news that night.” After the sinking, the trio were deemed unfit for sea, and Ted went to the RN Signal School, at the RN Barracks in Portsmouth, which was in the process of moving to Leydene as HMS Mercury. “I was sent out there to help out but it was more or less ‘leave him alone and let him do what he wants’,” said Ted. “I used to wander down the broad walks. The chap in charge was an old and bold signal bosun, and he came across me one day and said: ‘What are you doing?’ “I said I just wanted to forget, and he said: ‘You are never going to forget – you are a Naval curio and no one will let you forget’.” Ted then spent a year at HMS Royal Arthur, a hostilities-only training establishment in a converted holiday camp at Skegness, before he was declared fit for sea duties again, and he was back on the water after 18 months ashore. Again, luck was with Ted, for while he certainly did not have it easy for the remainder of the war and after, he emerged unscathed – “I was bloody lucky, I didn’t really get any damage at all,” he laughed. He was at the Sicily landings, Salerno and D-Day with Combined Ops HQ ship HMS Hilary, then with frigate HMS Kingsmill at the Walcheren landings. “I was terrified by the action side of it, but it was something entirely different so it didn’t really bring the Hood business back then,” said Ted. “The ships were never hit – a couple of near-misses with bombs, that sort of thing, but nothing else.” After the war, in another frigate, HMS Brissenden, Ted served on the Palestine patrols, then he spent over two years in the cruiser HMS Ceylon, including the Korean War. He took his officers’ promotion course and rejoined the Ceylon in time for the Suez crisis – but strangely, he never, in more than 30 years, sailed again through the Denmark Strait and over the wreck where so many friends and shipmates lay. Ted finally left the Service in 1973, his last appointment being on a leading rates’ leadership course at Whale Island. “I left as a two-striper with an MBE as a consolation prize,” said Ted. “I look back at my Royal Navy career with pride. I was sorry to leave, but the time had come, because I was in communications and the new technology was getting way above my head, so I had no regrets. “I had 35 years in, and I was thoroughly satisfied. I still have a sense of pride in the Navy. “I get quite sad when I look at the size of the Navy today, but, for example, four of us at the association were invited aboard HMS Newcastle, and when I looked round on a conducted tour I realised that that ship packed more firepower than Hood and quite a few others put together. “So although the Royal Navy has got smaller it’s still good, it’s still the best.” Ted’s fellow survivors are both long gone now, and Ted bears the brunt of the enduring fascination with the loss of a ship which symbolised British – and Royal Naval – power and pride between the wars. Tired of his role as a “Naval curio” as each anniversary rolled round, Ted is now more sparing in his interviews – although it is not because they bring everything back into sharp focus. That happens anyway. “Looking back, it’s still fresh in my mind – I do get quite emotional at times. For example, it takes a hell of a lot of getting out, that exaltation that I do every year at Boldre church for the memorial service,” he said. “It still affects me – I fill up. And ten years ago a psychiatrist told me that was natural – I said it was 50 years ago, but he said it was so deep-seated that I will never get rid of it.” Ted was invited out to the site of the sinking with a Danish ship some years ago, but his doctors blocked it, saying it would do him harm. His emotions also make it difficult for him to contemplate the prospect of divers going to the wreck, or pictures being beamed back from the sea-bed well over a mile down. “When the idea was first suggested I said ‘No, in no way.’ She is a war grave and should be treated as such,” he said. But members of the Hood Association were receptive to the idea. “At an AGM, a friend of longstanding said: ‘What is your objection, Ted?’ I said she’s a war grave and she shouldn’t be touched. “He said if you went into a cemetery and took a photo of your mother’s grave, would you regard that as desecration? I can see his point. “As the association agreed, I went along with it reluctantly, so long as they look, but don’t touch.” Ted since made the trip out to the site, and paid his own tribute to his shipmates. Ted bears no ill feelings toward those who brought about the destruction of his pride and joy, and he has met Bismarck survivors – around 110 were plucked from the sea by the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire after the German battlecruiser was sunk, little more than three days after she had despatched Hood. Around 2,100 German sailors died, many drowning as the Dorsetshire was forced to leave the scene, a reported sighting of a U-boat causing her commanding officer to make the safety of his ship a priority. “They were doing their job and we were doing ours,” said Ted. “One of the German survivors wrote a book about the Bismarck – he should have come over with a small German contingent to a reunion but he wasn’t very well. He actually died about three days later. He wrote a dedication in it: To the only living survivor of the Hood from one of the few surviving members of the Bismarck, in the desperate hope that such idiocy never happens again. “I think that sums it up.”

Fact File

Displacement: 41,200 tons (43,360

full load)

Ray Holden emailed me on 25th Jan 2006: I don't know if I have told you this before but in 1950 I served with Bob Tilburn who was one of the three survivors of Hood. Bob was rated up to Leading Seaman after the sinking, by their lords of the admiralty not his commanding officer, what we in the service called an ADMIRALTY MADE KILLICK which is navy slang for a leading hand. Admiralty rules and regulations state that beards, or FULL SETS should be keep in trim at all times but Bob had a very big bushy beard which was not trimmed possibly a perk for being admiralty made no one but their lordships could take that rank away from him.

http://www.hmshood.com/hoodtoday/2001expedition/index.htm

Gives details of when the Hood was found in 2001 showing damage to be even more extensive than was first imagined. The original construction cost was £6,025,000 (of which John Brown and Company Ltd, reportedly made £214,108).

HMS Hood contained 380 telephones at the time of her loss and had 3,874 electric light fittings. She had nearly 200 miles of permanent electric cable which weighed in at approximately 100 tons. General provisions for 4 months amounted to 320 tons, including one month's fresh meat. Breakfast consisted of 100 gallons of tea, four sides of bacon, 300 lbs of tomatoes, 600 lbs bread, 75 lbs of butter. Fuel consumption at full speed was 3 yards to the gallon and the crew got paid a total of £6000 per month. If you were to run three times around the ship it was one mile.

In the National Memorial

Arboretum stands this memorial: |