Scharnhorst

The Battle Of The North Cape

September 2004 Update: 02 April 2013

| This article is about the German Battle Cruiser Scharnhorst. To begin with I paint the picture from the channel "dash" to the Battle of the North Cape in which the Scharnhorst was sunk by British Naval Forces in December 1943. Why factors on land affected decisions and how the British Home Fleet was affected by her presence in northern waters. Links highlighted in Blue lead to other pages on my site of peripheral interest. |

1939 vintage, unmodified bow |

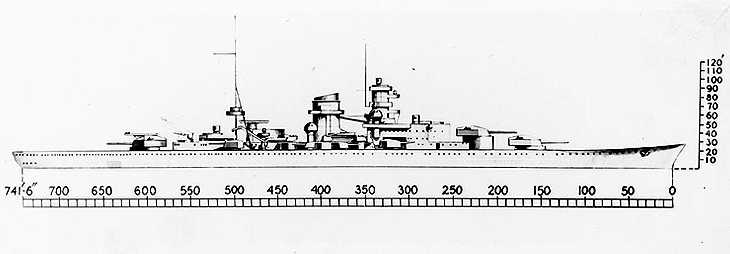

Scharnhorst, a 31,100-ton Gneisenau class battle-cruiser, was built at Wilhelmshaven, Germany. She was launched in October 1936 and she was commissioned in January 1939. Her first wartime operation was a sweep into the Iceland-Faeroes passage in late November 1939, in which the British armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi (see base of page) was sunk. In the spring of 1940 the Scharnhorst and her sister, Gneisenau, covered the conquest of Norway. They engaged the British battleship Renown on 9 April 1940 and sank the carrier HMS Glorious and two destroyers on 8 June. In the latter action, Scharnhorst was torpedoed. She was further damaged by a bomb a few days later and was under repair for most of the rest of 1940. This had been as a direct result of intelligence gathered by breaking the British naval code. The Germans knew where the Glorious was. Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, in his book Enigma - The Battle For The Code writes" ...the German cryptographers, who, unknown to the British, could read the Royal Navy's codes, were telling the German Navy the whereabouts of Britain's warships. One crucial signal, intercepted by the Germans, and read by them on June 2nd, revealed the exact position of HMS Glorious, the aircraft carrier, off the coast of Norway. It was one of the ships sent to protect the troops ships as they brought home the British Army". Hinlsey, in Bletchley Park, issued a warning "circulated in the OIC's logbook, but it failed to receive a wider circulation" The aircrafts commander was never given the intelligence which might have prompted him to fly off his aircraft to see what lay over the horizon. At 1715 hrs on 8 June 1940, Glorious spotted the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau closing fast. Minutes later they opened fire on HMS Glorious reducing her to a mangled, blazing mess full of mutilated corpses. The escorting destroyers were also sunk, leaving only 3 survivors. From 22 January until 22 March 1941 Scharnhorst and Gneisenau operated in the Atlantic, sinking several ships and severely threatening British supply lines. While at Brest, France, following this operation, the German ships were the targets of repeated air attacks. The resulting damage kept them non-operational into late 1941, when it was decided to concentrate German surface naval power in the Norwegian theatre. Since it was too risky to attempt the redeployment via the North Atlantic, on 11-13 February 1942 the two battle-cruisers and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen made a daring "dash" through the English Channel to reach Germany. In the book "The Battle of The Narrow Seas" by Peter Scott, he describes the scenario from the point of the men of the Motor Gun Boats. |

|

When the Germans decided to risk an all out "channel dash" for their three cruisers at Brest, some authors give the impression that the British were caught napping and not ready for such an event. This maybe so to a certain extent but we must take into consideration the conditions at the time. The alternative of running the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen around the northern route risked many days at sea, running into British ships constantly on patrol in these waters and giving the Home Fleet time to ready, weigh anchor and steam out from Scapa Flow for an ambush whilst constantly shadowing these three from air and sea. And U boats would have been warned off as a matter of course in case they were mistaken for Allied vessels. Bletchley Park would almost certainly have intercepted such signals and the Royal Navy would have been ready. Later in the war, Admiral Doenitz suspected such an occurrence had taken place but his suspicions fell on deaf ears. This would not have been a deciding factor with the German High Command who did not know, and never did, that their enigma codes were broken and that Britain read all their radio traffic, albeit at a delay, sometimes only a few hours, sometimes a day or two. Whether Bletchley Park had received any radio traffic concerning the "dash" is not known, and even if they had, there could have been a delay in deciphering which occurred quite often when key codes on the enigma machine had been changed. On the days of 11th and 12 February 1943 if this was the case, I do not know. Also to be taken into consideration was the fact that this was February, the height of the winter stormy season, the ships were at anchor in Brest and had been for some time. Air Reconnaissance was possibly grounded and, as you will read shortly, the seas were "heavy" which means of course, windy and rough! Taking all the above factors into consideration, except of course for Enigma, the Germans would have been awaiting such a time to make their run. They would have made all preparations under the strictest secrecy, especially in Brest, where the French Resistance would have eyes and ears. They would also have waited for such weather as this before suddenly weighing anchor and racing out at 27 knots to head for Germany, not all that far a distance away. |

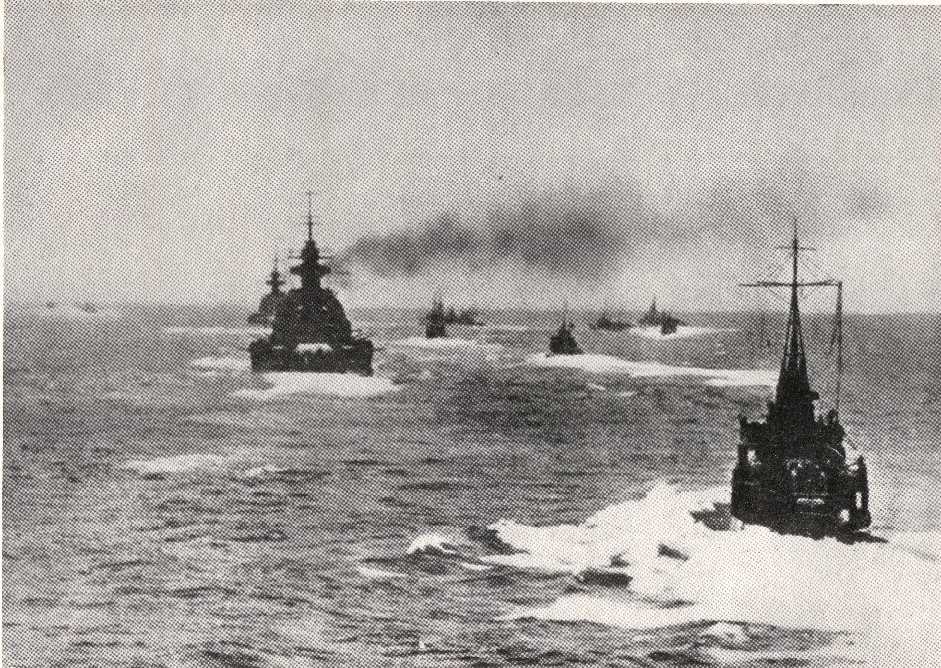

Scharnhorst & Gneisenau, taken from Prinz Eugen, on the Channel Dash |

When spotted, the ships and their escorts had almost reached Bologne and there would certainly have been no time for any large vessels in, for example, Portsmouth to set sail. Even if they had managed to do so, they would have been following the Germans without a hope in hell of catching up given the short distances involved in the capital ships reaching Germany. Britain sent out a small force of MTB's (Motor Torpedo Boats) in an effort to hit these targets. Each MTB only carried 2 torpedoes, already loaded into their respective tubes and once fired, there would be no time to race back to Dover for a refill! It would be a one off, split second timing, hit or miss effort against fast moving targets. Targets that were, in fact, moving faster than the MTB's of that time could travel, 27 knots against 24 knots. The Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen would have been able, in an emergency, to probably have made a few knots more. Scharnhorst certainly could as we shall find out later on. Another factor in the German's favour for a Channel dash was that they could enjoy full supporting land based fighter cover, which they did, coupled with the usual destroyer escort for these ships and plenty of E Boats to provide an outer defensive screen. An eye witness will shortly describe the fighter cover as "swarming". Quite probably, every available fighter based in Northern France was, at one time or other, involved in providing this massive umbrella over the ships. As these capital ships approached Bologne, a telephone rang in a small office in Dover were a Lt Comdr Pumphrey was catching up on some paperwork. It was an unsecure line and the Royal Navy Officer assumed it was the Stores. It was now 1135 hrs on 12th February 1942. In fact, on the phone, was Captain Day, the Chief of Staff. He informed Pumphrey that these battle-cruisers were now off Bologne and asked him how soon could he be ready? Pumphrey replied that his boats were at 4 hours notice to sail but would do what he could. He then dashed off to the Wardroom and told all to get ready for sea immediately then ran off to the Ops Room where they thought it was a joke. "There was a mad rush for the boats. Luckily all available MTB's were in running order". Usually mechanics would be busy doing repairs when in dock, but this time they were all in order. "There wasn't a moment to lose if we were to make an interception of ships travelling at 27 knots in out 24 knot boats. We formed up and screamed out of the harbour at full speed and passed the breakwater at 1155 hrs, 20 minutes from the telephone call! There were five of us, Boats 221, 219, 44, 45 and 48. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were something of a legend to us, and here we were, racing to attack them, in broad daylight!" Pumphrey had taken command of 221 as his own MTB was in dock and the commander of 221 had been ashore at the Stores, there had been no time to find him. They set course for No 2 buoy and the going was "pretty rough" with a strong westerly wind "but the weather was behind us so it didn't affect speed too much" At 1210 hrs they could all see the "swarm" of fighters, Me 109s. A Squadron of these peeled away and roared low enough over the racing MTB's that "we could see the metal frames of the pilots flying goggles". The MTB's opened fire on this Squadron, MTB 45 clipped sections of wing off one Me109 but the 109s for some reason did not attack, presumably on orders to await the expected RAF bombers. At the same time, through thick patches of smoke, 10 E Boats made their appearance on a course barring the MTB's from an attack run on the cruisers. Problems struck MTB 44 when one of her engines "conked out" and she fell "miles astern". The remaining four MTB's altered course towards the E boats. The "temptation to those E Boats to turn towards us, close the range, and clean us up, must have been almost irresistible, but they resisted it. The initiative stayed with me". At 1000 yards both sides opened fire. Then the main force appeared out of the smoke screen, the Prinz Eugen in the lead, followed by the two battle-cruisers, 4000 yards away. The "swarm" of Me 109s still above them like angry wasps. Pumphrey noted that their armament was fore and aft and estimated speed at 27 knots. "The situation was impossible. The E boats barred the path for an MTB attack. I put on emergency speed thinking it would be a waste of time and I was right. The E boats added a knot or two, maintaining their excellent defensive position". Pumphrey had two alternatives, try to battle a way through the E Boats or to try and fire the torpedoes at long range. The MTB's were on an ideal vector, 50 degrees on the bow of the leading battle-cruiser, but the range was "hopelessly long". Pumphrey admits to making the wrong decision and altered course to try and fight his way through the E Boats. "It was a mad thing to do, the inevitable result would have been the loss of all the boats before the range could be reduced to a reasonable one, say 2000 yards." Fate took its own strange hand and Pumphrey's starboard engine "conked out" and his speed fell back to 16 knots. Under these circumstances he had only one alternative left, to hold and to fire at 4000 yards. When the E Boats were about 200 yards away they fired their torpedoes. Even at such a short range, the fire from the E Boats scarcely touched the MTB's as the seas were "too rough". After torpedoes were away "we turned away without much hope of a hit. The whole operation was most unsatisfactory and 3 minutes after we had fired, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned away at 90 degrees from us and our last hope of a hit disappeared". One of the MTB's, 44, recovered from his dead engine, saw a brief opportunity when Prinz Eugen turned towards them by 50 degrees and he fired, although the target was quite distant. Pumphrey said that "after the allotted torpedo run time I saw a plume of water rise under Prinz Eugen's bridge, not a characteristic torpedo hit, but what else could it have been?" The E boats then made smoke and through this emerged a Narvik Class destroyer, at least Pumphrey identified it as such, but it was in fact "Friedrich Ihn" a Maas class destroyer. The destroyer was faster than the MTB's and the situation looked desperate. Fate again took a welcome hand with the appearance of two MGB's (Motor Gun Boats), the 41 and the 43. Lt Stewart Gould, commanding, was angry at having missed "the fun" and he was in no mood "to be embarrassed by a mere Narvik". The two 63 foot boats went at the destroyer, blazing away with their Oerlikon's. Stewart Gould intended to drop depth charges as close to the destroyer as possible. The destroyer mistook them for fresh MTB's, loaded with torpedoes, and turned away to rejoin the others. MGB's do not carry torpedo tubes! Minelayers had succeeded in laying a partial minefield ahead of the ships and caused damage which led to Scharnhorst being docked in Gdynia for repairs which lasted until her subsequent move to join up with Tirpitz, in Norway, the following year. This account of the Channel Dash was published in "The Battle of The Narrow Seas" by Lt Comd Peter Scott, MBE, DSC + Bar, RNVR in 1945. He served with these "spitfires of the sea" with distinction, as did their very brave crews. Repair work, a grounding and her always troublesome steam power plant kept Scharnhorst out of action until March 1943, when she went to northern Norway to join the battleship Tirpitz and the Lutzow plus 2 flotilla's of destroyers threatening the convoy route to the USSR. In March 1943 the Scharnhorst had left Gdynia heading for Norway. She had been in Gdynia for repairs following her famous channel "dash" in which she had incurred mine damage which had been laid deliberately in her path by British coastal forces. During bad weather the Scharnhorst slipped out of Gotenhafen and sailed to Trondheim via Bergen with a heavy escort and large air cover, under the codename of Operation Zauberflotte. She then sailed from Trondheim, accompanied by the Tirpitz, to join up with the Lutzow at Bogen Bay, not far from Narvik on 12 March 1943. On March 22 they then sailed to Altenfjord, arriving on 24th March. As this was a direct threat to the Arctic convoys the disposition of the Home Fleet had to be amended to meet any possible threat. The carriers Furious and Indomitable stood by on the Clyde and the Battleship HMS Anson sailed for Seidisfjord, Iceland. To cover for the eventuality of an Atlantic Bismarck style breakout, patrols in the Denmark Straits and the Faeroes - Iceland gap were stepped up. Additional cruisers also left Iceland to cover convoy RA53. Admiral Doenitz had only recently taken over the Kriegsmarine from Admiral Roeder. Before that he had been in charge of the U Boat Arm. Up to this time Hitler, mindful of what had happened to the Bismarck in May 1941, refused to allow his capital ships into action unless all conditions were favourable for a victory, and that the exact positions of all the British capital ships were known, as well as the carriers, of which he was particularly wary. Indeed, men were already being drafted away from the capital ships to replace crews lost in the U boats and to crew new U Boats. In February 1943, Doenitz succeeded in changing Hitler's mind and had been told that he could send his ships out at "the next favourable opportunity". Hitler had said that the "time for great ships was over, I would rather have the steel and nickel from these ships than send them into battle again". Hitler correctly pointed out that, in the Pacific, the value of capital ships had been lessened by carrier borne aircraft and that the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe could not develop satisfactory cooperation. This was to prove exactly right in the coming months. In the winter months of 1942/1943 the despatch of convoys to and from Russia had been very successful but the very presence of these ships in Norwegian waters was taking the shine of any elation that may have been felt in the Home Fleet or the Admiralty. Although a couple of merchantmen had been sunk, by U Boats, large amounts of essential supplies including tanks and planes had successfully been delivered to Russia. Admiral Tovey, Commander in Chief Home Fleet, therefore viewed the coming months with their long arctic summer daylight hours, with some trepidation. The presence of these ships dictated everything tactically and tied down a great number of large ships which could have been used elsewhere. He recommended a halt to convoys to Russia. Events in the Atlantic were to come to the Admiralty's aid in reaching a decision. The battle against the U Boat was reaching a climax and the decision was taken to move all available escorts to the command of Admiral Sir Max Horton, Commander in Chief Western Approaches, based in Liverpool. To say that the Soviets were not best pleased would be an understatement. Stalingrad had been relieved on 2 February 1943, so the imminent danger of a Soviet collapse had receded and Soviet industry, moved to the Urals, had recovered and was beginning to churn out massive quantities of armaments for its forces. On the 8 May 1943, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser assumed command of the Home Fleet. He was an outstanding gunnery officer who had played a leading role in the production of the new main armament on the newest of Britain's battleships, the King George V Class. He had also been Tovey's deputy, therefore transition was minimal and he needed very little time to get to grips with the command. Parts of the Home Fleet had been sent to the Mediterranean for the invasion of Sicily and some American ships had sailed from Argentia, Newfoundland to be based at Scapa Flow with the Home Fleet. Battleships South Dakota and Alabama and 5 US destroyers. Fraser now had also 2 King George V class battleships. A combined armament of 20 x 14 inch guns and 18 x 16 inch guns to deal with any possible German surface offensive. These US Forces, though not lacking in enthusiasm, completely lacked any form of anti submarine training. When the combined fleet sailed for ranging exercises, the American's spent more time trying to kill porpoises than U boats! Although no convoys were running to Russia during these months the very threat of the Tirpitz etc was to remain in the forefront of Fraser's planning. In September 1943 Fraser had a very good "picture" of the exact whereabouts of the German Battle Group, thanks to intelligence from Norwegian Resistance, Ultra signals and Air Reconnaissance. Scharnhorst, Tirpitz and Lutzow were anchored in inlets off Altenfjord. Due to the Tirpitz being damaged by the heroic exploits of the Royal Navy's X Craft, and the return to Germany of the Lutzow, the Scharnhorst was now the Royal Navy's chief concern and the only operational German capital ship in Northern waters. Ongoing repairs were still being conducted on Tirpitz, so for the time being, she was considered "out of it". On 21 October, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound died and was succeeded by Admiral Cunningham, fresh from victories in the Mediterranean. within 3 months of his appointment, the Royal Navy would have its excellent victory in the Arctic seas. The surrender of the entire German 6th Army at Stalingrad was followed by the smashing of the German summer offensive by the biggest tank battle ever, at Kursk, in July 1943. By Sept 1943, the Germans were in headlong retreat, from Moscow in the north to Baku in the south. Smolensk was taken by the Red Army on Sept 25th. It was at this time that the Soviets "requested" the resumption of the Arctic convoys. Diplomacy between, on one side the UK and the USA and, on the other, the USSR was acrimonious. One Stalin reply to Churchill was so bad, that he refused to receive it, returning it unread to the Soviet Ambassador. Nevertheless, convoys were to resume and ships, stranded in Kola since the Spring, had to be returned to the UK. 10 destroyers, 2 minesweepers and a corvette left Iceland on 23 October, along with 5 minesweepers and 6 sub chasers being given to the Red Navy. The returning convoy reached Loch Ewe without incident on 14th November. By October 1943 the German Battle Group North consisted of the Scharnhorst, under the command of Kapitan Julius Hintze, and the 4th and 6th Destroyer Flotilla's. On the 17th November the 6th flotilla was ordered back to the Baltic. The 4th Flotilla consisted of the new large Z Type destroyers. Each was over 400 foot long with 5 x 15cm guns and 8 torpedo tubes. They were both larger and faster than their British counterparts. |

|

|

Rear Admiral Erich Bey took command of the Battle Group on the 8th November. His previous appointment had been Flag Officer (Destroyers). He had been in command of the destroyers during the channel dash. He had little in the way of supporting staff and his orders were "unworkable" containing so many restraints. Also he could not make his mind up about the use of the destroyer flotilla, whether they should support Scharnhorst, or vice versa. apparently, in the German High Command, only Doenitz was optimistic about using Scharnhorst against convoys. On December 19th Doenitz told Hitler that "Scharnhorst would attack the next convoy". At the end of 1943, Arctic convoys to Russia were once again settling down to a routine. Due to the ever present threat from the Scharnhorst, escorts where, by necessity, on the "heavy side" with screening destroyers being covered with cruisers and capital ships. For example, convoy JW/RA 55 had, to accompany it, cruisers Belfast, Sheffield and Jamaica and the battleship Duke of York. On Dec 22nd, a weather flight, a Do 217, sighted the convoy and reported back to Norway that it was a "troop convoy" and this was immediately interpreted as the invasion of Norway. apart from increased air patrols and U boat activity, Scharnhorst was put on a 3 hour notice to sail. But, the same day, the report was rectified to "a convoy". Admiral Fraser, on board Duke of York, was concerned that the convoy appeared exposed. Accordingly he thought it worthwhile to break radio silence to make amendments to the positions of his ships. He also ordered the Duke of York and her accompanying cruiser Jamaica, to increase speed. He ordered the convoy to reverse course for a while, not an easy thing for the convoy to do. The combination of which, should the Scharnhorst set sail, was that she would not arrive in the vicinity of the convoy until after dark. He increased the destroyer screen by four more by removing them from the untouched homeward bound convoy RA55a as it was clear that this had totally evaded detection. By nightfall on 24th December there was still no news of Scharnhorst but the two convoys were now converging and she could still mount an attack. In spite of her lack of fighting since 1941, Fraser must have had some sailors 6th sense about the coming few days. The weather was Gale Force 8 and U Boat transmissions were being detected by HF/DF (High Frequency Direction Finding) on more than one heading. At 0900 hrs Christmas Day, the U-716 fired an acoustic torpedo (gnat) at a destroyer, but missed. Fraser had one ace-in-the-hole which gave him almost complete access to German naval signals. For quite some time Britain had access to these via the enigma machine mentioned earlier, at Bletchley Park. Such signals were given the caveat "ULTRA", treated with the utmost secrecy by the British and accessed by a very select few. Fraser was one of these few. |

HMS Duke of York |

|

At 0216 hrs 26th December, such a message arrived on board Duke of York stating that the Scharnhorst probably sailed at 1800 hrs 25 December. 8 hours previously. To cover the source of the intelligence and the fact that the convoy commodore did not have access to ULTRA, the Admiralty sent out the following signal "Admiralty appreciates Scharnhorst is at sea". No doubt, if this was intercepted by the German BDienst intelligence service, it would assume Norwegian Resistance had seen her slip her moorings and make her way down the fjords towards the open sea, or a patrolling submarine had reported in. On board the British ships confidence was very high and crews felt that, if they met, they would soon despatch her to a watery grave. |

The Beast Was Out!

|

| It was not until 1955 hrs on Christmas Day that Scharnhorst and the destroyers of the 4th Flotilla (Z Type) passed through the net barrier of Lange Inlet, into Altenfjord and headed up the length of Stjernfjord, at 17 knots. German High Command and Group North Command were already having grave doubts, especially when the Luftwaffe reported that there could be no reconnaissance flights due to the bad weather. The German Battle-Cruiser Scharnhorst was now on her way to her destiny, heading north at 25 knots, into worsening weather. Seas were washing completely over the destroyer escorts battling along with her. At 0300 hrs 26th December, Bey received a signal confirming the operation was to proceed. By 0700 hrs the Scharnhorst's navigator reckoned that they were now within 30 miles of the convoy, and ahead of it, another 40 minutes and the convoy should be in view. At 0820 hrs, for some unknown reason, Admiral Bey turned the Scharnhorst to the north. However, Bey neglected to inform the 4th Flotilla who sailed blindly on at 90 degrees to the Scharnhorst, contact soon being lost, never to be regained. |

The Battle Of The North Cape Time had run out. At 0926 hrs, without any warning from the radar or her look outs a star shell burst above Scharnhorst, illuminating her like a great silver ghost on a darkened sea. Scharnhorst had been caught by surprise, but nobody else was! Fraser had been drawing his web closer in, marshalling his ships. He had already turned the convoy away from the raider. Force 1 was in contact and Force 2, with the Duke of York was steaming hard. All the British participants were aware of exact positions of each other, Fraser did not want the same mistakes made from an earlier Tirpitz encounter with the Home Fleet. By the same token Admiral Bey did not have a clue that British capital ships were, at the moment, closing in, not until 0926 hrs anyway! HMS Belfast had got her radar fix at 0840 hrs, Scharnhorst was actually between them and the convoy! If Admiral Bey had been a bit more determined he might have caused considerable damage to the convoy before becoming engaged with the Royal Navy. Doenitz himself, was later to say the same thing. HMS Sheffield got the first visual sighting at 0921 hrs signalling "enemy in sight, bearing 222 degrees, 13000 yds". Then Belfast fired the star shell but did not see the enemy. At 0929 hrs the order to engage the enemy was given. All the ships, except Norfolk, had "flashless cordite" and as a consequence, when the ships opened fire, Norfolk's gun flashes made her the prime target for the return of fire from the Scharnhorst. Norfolk loosed off no less than 6 x 8 gun salvo's in only 2 minutes, thanks to the high standard of the training of her gun crews and, with mostly manual loading, as the cruiser ploughed through heavy seas! Norfolk's second salvo smashed the mattress aerial of Scharnhorst's Seetakt radar, destroying the port HA director and wounding 4 of her crew. Scharnhorst increased speed to disengage, getting up to nearly 30 knots and soon opened the range to 24000 yards inside 20 minutes of the first star shell. At 1020 hrs contact was lost. |

HMS Sheffield |

On board the Duke of York, Fraser was worried. After contact was reported lost he considered his options. However, his course of action was decided when he received a signal from the Belfast ay 1205 hrs "Unknown contact, 075 degrees, 13 miles". Belfast (and Force 1) were back in contact. Fraser ordered his ships, Force 2, to turn to course and close. Sheffield confirmed contact at 1211 hrs, followed by Norfolk at 1214 hrs. Force 1 and Scharnhorst were closing at a combined speed of 40 knots. Admiral Burnett, on board Belfast, had made a correct "guess" after they had lost Scharnhorst the first time and had moved his ships accordingly. Now they were approaching each other head on! Once again, it was the Sheffield who announced "enemy in sight" and, at 1220 hrs, Force 1 was ordered to "Open Fire!" For the second time, Scharnhorst was taken completely by surprise. However, when she did reply, her shooting was quite accurate. Norfolk again bore the brunt of her replies. One 11 inch shell hit X Turret, putting it out of action. Another hit Norfolk on the starboard side, amidships, killing 8 men near the secondary damage control headquarters. Chief Engine Room Artificer Cardey later wrote: "I was standing in the middle of the compartment by the dials when there was a vivid flash and bits of metal rained down. One hit an engine room rating, who was just beside me, in the leg. Another piece of metal tore off the tops of two fingers of a man who had his hand on a lever, he did not know it had happened until a quarter of an hour later. Water began to pour down through the engine room hatches. Some fuel oil came with it, and I saw one fellow looking like a polished ebony statue because he had been covered from head to foot with the black oil. He was carrying on as if nothing had happened. I went across to the dials and found that the pressure was not affected. Some of the lights had gone out and there was a good deal of smoke, and we knew by the smell that the fire was raging somewhere. They were too busy to come and tell us what happened. Every man in the engine room had his work to do so we just carried on and only heard odd bits of information when they brought the sandwiches down and so on. We kept the engines going at full speed for six hours after the ship was hit. There was about three feet of water swishing about in the bilges below the engine room and the lower plates were covered." And CERA Davies wrote of the "Hostilities Only" men: "As an old RN man I can tell you they were something to be proud of. Not one faltered, and I suppose we all were, at the back of our minds, expecting something to happen any minute". "Hostilities Only" men were sailors who had signed up "for the duration" and would leave the Royal Navy at the outbreak of peace. The destroyers were buzzing round Scharnhorst like angry wasps. "Musketeer" got close enough to observe the hits from her guns landing. Scharnhorst increased speed again and began to pull away from Force 1. Burnett, on Belfast, resolved to shadow her until Force 2 was in a position to intercept her. The whole engagement had lasted 20 minutes. Force 1 had taken up position port side of the battle-cruiser, about 7 1/2 miles, just outside visible range. At 1300 hrs Admiral Bey turned Scharnhorst onto a course of 155 degrees which would taken her home. He was following orders but Doenitz was still critical stating that Scharnhorst could have got through to the convoy easily enough. Mystery surrounds the fact that Force 2 had previously been sighted by the Luftwaffe. Bey had received a sighting report at 1530 hrs the previous day. German intelligence had a wealth of intelligence on their hands but little was conveyed to Bey warning him of the closing of the British net, or of the capital ships about him. Throughout the afternoon Burnett's ships hung on to Scharnhorst. Every 20 minutes or so, Burnett would report direction, speed and position. It was a superb bit of shadowing, described by Fraser as "exemplary". Tovey wrote to the Captain of HMS Belfast: "I was following your intercepts on the chart, and I know that you and your fine ship would never let go of the brute unless the weather made it absolutely impossible for you to keep up. The combination of the gallant attack you and other cruisers made on the Scharnhorst, coupled with your magnificent shadowing, is as fine an example of cruiser work as has ever been seen." |

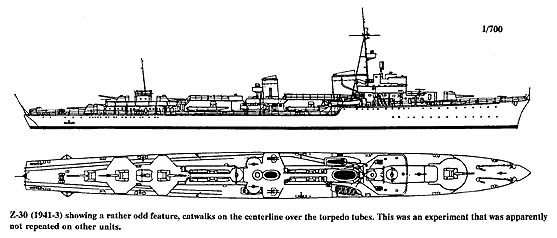

Z Class German Destroyer |

Fraser could not tell if D4 (4th Flotilla destroyers) were with Scharnhorst, so he signalled Burnett and received the reply "one heavy ship" thus removing any doubt in Fraser's mind. Fraser now knew that action would be joined at about 1630 hrs. Burnett signalled that he was "by himself" shadowing Scharnhorst at about 1600 hrs. However, this was not quite true, as Musketeer and three other destroyers were risking all by pounding through the heavy seas at 30 knots, against a head sea, regardless of damage than could ensue from such a pounding. Norfolk had dropped back to fight a fire on board, but brilliant work by her fire crews saw Norfolk catching up again by 1700 hrs. Sheffield also fell back and never really caught up, being 10 miles behind Belfast for the remainder of the engagement. Belfast's Captain recorded that he could never understand why the Scharnhorst, who must have seen Belfast on her radar, never turned and engaged her, driving her off or even sinking her? The Duke of York picked up the Scharnhorst on her radar at 1617 hrs, followed shortly by Belfast locating Duke of York on her own radar. The first thing noticed when Scharnhorst came into visual range was that her guns were trained fore and aft. For the third time in the same day Scharnhorst had been caught completely by surprise! For the guns crews of the Duke of York, the waiting was over, firing her first salvo at 1651 hrs. The first salvo from Duke of York hit the Scharnhorst low down and forward, with "A" turret becoming immediately inoperable. Destroyers were ordered in for a torpedo attack. Scharnhorst had again recovered from her shock and returned fire accurately. HMS Savage got in so close that when the Scharnhorst was illuminated by star shell, Savage was lit up as well. Cmdr Meyrick on Savage actually had to turn away and increase range in order to attempt a torpedo attack. As the afternoon wore on, Scharnhorst's gunnery became so accurate that it was inevitable that the Duke of York would receive some hits. The radar jammer was put out of action and then a remarkable sequence of events took place which was to find its way into "legend". One of the Scharnhorst's 11 inch shells screamed right through one of the legs of the Duke of York's tripod foremast, travelling only feet beneath the radar office and its three occupants! The radar ceased working even though, after checks, all appeared to be in perfect working order. Lt Bates, RNVR recorded that "I switched off all the office lights and climbed up into the aerial compartment. By feeling about in the dark and with the help of a small pocket torch, I found the aerials were pointing up to the sky. I got the aerials horizontal and re-stabilised them by their gyroscope and the echoes were restored." So it had been the terrific shock of the passing of the 11 inch shell through the mast which had made the aerials topple over! This episode of the battle very soon became legend, not only on board the Duke of York, but throughout the entire fleet - that the "miraculous repair of the radar had been due to Bates having climbed the mast and held the wires together single-handedly. He received the nickname "Barehand Bates" and nothing he could say could dispel the legend, which also gained official recognition throughout Great Britain. It was after all, just the thing that the newspapers thrived upon as a means of stiffening morale and resolve in a war torn country. "Barehand Bates" received the DSC for his efforts. Able Seamen Badkin and Whitton were also rewarded for their efforts with a DSM each. In another straddle the main mast was hit causing the temporary loss of the Type 281 air warning radar set and Admiral Fraser's barge got wrecked! However, Scharnhorst was, yet again, showing signs of getting away as she began to open up the range. By 1717 hrs she was out of visual range of the Duke of York who continued firing by radar. At 1824 hrs the Battleship stopped firing. Fraser signalled to Burnett that he was going to remain with the convoy as they had no chance of closing the Scharnhorst. Suddenly the range counters which had been rapidly clicking up the range between the ships started to slow down, then showed that they were again closing with the target - Scharnhorst was slowing down! The Royal Navy began gaining on her as the range counters started to decrease the distances between them and the target. It is quite possible that they caught the Scharnhorst napping for the fourth incredible time that day. It was thought possible that the Scharnhorst had either switched off her radar, so that the Royal Navy could not detect the emissions, or that it was out of order. But survivors later picked up recalled that announcements were heard about contacts to starboard. But nobody ordered the main guns to be trained in that direction and indeed, when the alarm sounded, most of her gun crews were stood down! |

Duke of York Fires a Salvo |

|

The Duke of York's first salvo scored a hit above the water line, a second wrecked the already inoperable "A" Turret. The consequent explosion detonated charges in "A" magazine which spread to "B" magazine. Both magazines had to be partially flooded by the damage control teams. At this time the gunnery from Scharnhorst was, at best, piecemeal. The crews manning the 11 inch guns fought well and hard, but closer quarter secondary weapons were badly handled with countermanding orders being given regarding types of shells to be loaded. In the case of the 105mm guns, the crews were below decks, having been stood down due to the badly protected positions of their guns. Scharnhorst's speed fell down after a 14 inch shell hit the starboard side and put a boiler out of action. It was recalled on the bridge of the Scharnhorst that the speed "dropped from 29 knots down to 22 knots rapidly. At this time the destroyers of Cmdr Meyrick were now rapidly gaining on the battle-cruiser. HMS Savage and HMS Saumarez were 10000 yards off the stern and HMS Scorpion and the Norwegian destroyer Stord were off the starboard beam. Scharnhorst fired upon them when they were within 8000 yards, but as her 105mm guns were stood down she lacked proper anti destroyer armament. Savage and Saumarez drew most of the enemy's fire but Stord and Scorpion appeared not to have been spotted, coming in from the south east. Both fired torpedoes at the Scharnhorst. For the Norwegians aboard Stord there was vengeance in the air, a unique chance to strike back at the enemy occupying their country. Lt Cmdr Storeheill, Royal Norwegian Navy, was determined not to miss this opportunity, pressing home his attack to the limit. Scorpion's commander remarked that they thought Stord was going to ram Scharnhorst, so determined was the Stord's attack. Only one torpedo was seen to hit and it is impossible to determine from which destroyer this came. Meanwhile Scharnhorst presented herself to Savage and Saumarez who duly launched torpedoes at 1853 hrs and Savage recorded 3 hits of hers on the battle-cruiser. Saumarez was badly beaten up on her approach, slowing to only 8 knots due to damage she still managed to fire off 4 torpedoes. Again 3 hits were recorded, one in a boiler room. The cruisers Belfast and Jamaica and the Battleship Duke of York were witnessing a pyrotechnic display of tracer and gun flashes. By this time the radar on the Duke of York had been repaired and she was tracking the Scharnhorst at 22000 yards. The Battleships Fire control was able to switch between visual and radar firing effortlessly. Scharnhorst turned directly towards force 2 and the range came down quickly. Then she turned 90 degrees to them and the Duke of York and the Jamaica opened fire at 10400 yards. This appeared to again have caught the Scharnhorst out, the Duke of York salvo hit aft, causing immense damage, the next few salvo's were fired in rapid succession and literally tore the Scharnhorst apart. Bey signalled to Berlin at 1730 hrs that he was "surrounded by heavy units" and at 1825 hrs, "We shall fight to the last shell". Norfolk now began firing from the north but had to check fire due to difficulties in identifying one unit from another. Belfast was also now firing and registering hits. The death of the Scharnhorst was now as inevitable as imminent. Her speed had fallen off to 5 knots but she held steady, steaming north. Lt Vernon Merry, RNVR, who was Admiral Fraser's Flag Lieutenant, wrote: " Every time we hit her, it was like stoking up a huge fire, with flames and sparks flying up the chimney. Every time a salvo landed, there was this great gust of flame roaring into the air, just as though we were prodding a huge fire with a poker". At 1920 hrs Fraser ordered Belfast and Jamaica in closer to the stricken Scharnhorst and told them to finish off with torpedoes. Meanwhile Duke of York continued salvo after salvo in quick succession until, at 1928 hrs, she checked fire, to allow the Belfast and Jamaica to fire their torpedoes. Only light, uncoordinated fire was coming from Scharnhorst as Jamaica fired 3 torpedoes but one misfired and she claimed no hits. Shortly afterwards Belfast also fired, one of which may have hit. Burnett claimed to his dying day that Belfast administered the "coup de grace". Both cruisers came about to fire their remaining torpedoes. Jamaica fired 3 but could not see any hits due to the thick smoke enveloping Scharnhorst. But, at the correct time for the torpedo run, underwater explosions were heard and it is assumed that 2 torpedoes had hit home. Belfast broke away as the sea became "infested" with Musketeer, Matchless, Virago and Opportune of 36 Division. These four had had a long hard slog through the heavy seas, to make this battle. |

HMS Opportune |

Fisher's four destroyers would not be put off their prey at the last minute so Belfast steamed away to assume an outlying position and the four destroyers raced in on the attack. They got in so close that "we could smell the fires burning on the ship as she was pounded again by the battleship. At 1930 hrs Matchless and Musketeer attacked on the port side whilst Opportune and Virago, the starboard. Opportune fired 2 salvos claiming two hits. virago, less than 2 months out of her builders and with a crew who had never been to see before, fired 7 torpedoes at 2800 yards and observed 2 hits. Matchless then fired 4 torpedoes and observed at least 3 hits. Matchless was having problems bring her tubes to bear, as the heavy seas had strained the gears, turned for another go but as she came in, Scharnhorst was not there - she had gone down. No ship actually saw her go down but a distinctive heavy underwater explosion was both felt and heard in the ships above. Helmut Boekhoff, survivor, recalled that he turned and saw, in the light of a star shell, the Scharnhorst turned right around and he could see a propeller still turning. Then all of a sudden he saw he go down, come back up again, then suddenly, she was gone. After she had disappeared he felt a "tremendous trummel" in his stomach and legs as there was a big explosion underwater. At 1948 hrs Belfast fired a star shell, all they saw was a raft covered with oil soaked German sailors, "it was a dreadful sight". They thought at the time that the sailors were screaming but as Helmut Boekhoff recalls: "The men were screaming and shouting "Scharnhorst - hip hip hooray, hip hip hooray and he was certain that a song was coming up "On A Sailors Grave, No Roses Grow". After the explosion underwater he turned to the other sailors, some swimming between bits of rubbish and clinging onto other pieces, still shouting "Heil our Fuhrer" and "Scharnhorst - hip hip hooray" and he thought to himself "pscht, what a waste". Fraser ordered all ships out of the immediate area whilst ships with torpedoes still on board "just in case" and a destroyer equipped with a searchlight was sent in to check the area. Matchless' searchlight piercing the Arctic night. In a superb piece of seamanship, Lt Comdr Clouston, Scorpion's Captain, stopped up wind of the survivors, keeping them in the lee, calm water, and drifted in gently. Those he was able to rescue spoke in sincere admiration of his skills. Scorpion succeeded in rescuing 30 men although all around drifted bodies, obviously dead. Fraser asked Scorpion for confirmation that Scharnhorst had gone down, which Clouston confirmed. At 2035 hrs the Duke of York broadcast at full power to Scapa WT "Scharnhorst Sunk". At 2136 hrs came the reply "Grand. Well done". I would imagine that the German High Command in Berlin heard that signal!! Fraser wished to save as many German sailors as possible but, at 2040 hrs, he received an ULTRA traffic signal stating that U Boats in the area had been freed of all restraints of attacks on warships, one wolf pack was known to be in the region and this indicated that German High Command was only too well aware that Scharnhorst had gone down. Reluctantly Fraser ordered all ships from the area and resume passage to Kola. Saumarez, badly mauled in the attack, made her own way slowly and, after pausing to bury her dead, arrived safely at Kola on the 27th December in the evening a few hours after the rest. Survivors were able to give some details of the end of the battle-cruiser. From when the Duke of York had opened fire at 1901 hrs, the Scharnhorst had been pounded to pieces. "C" Turret had been able to fire right to the end, when ammunition ran out shells were passed from "A" Turret. Not one of the Duke of York's salvo's had penetrated the heavily armoured deck, but had wrought havoc above, leaving only mangled wreckage. As none of her medical staff had survived the sinking it was assumed that they had stayed with the wounded to the end, similar scenario to the sinking of the Bismarck 2 1/2 years earlier. Above the deck the P1 15cm mounting had been destroyed. The hangar was hit and the aircraft destroyed thereby causing a large fire. The starboard 105mm mounting had been hit, a shell landed near the funnel, also on the starboard side and another 'tween decks on the port side. Most of the superstructure was a mangled mess with medical teams trying to climb through to reach wounded sailors. The starboard anchor had been shot away. "B" Turret was hit and ventilation was out of action. When fired, the guns released thick acrid smoke into the turret causing the men breathing problems. The upper deck was littered with bodies which were washed overboard as the ship heeled. Gunfire did not sink the Scharnhorst, it was the torpedoes which sank her in the end. I think here comparisons can be drawn with HMS Hood which, although planned, did not have an armoured deck. A shell from the Bismarck hit her through the deck into a magazine which, in an instant, blew up the entire ship. The Duke of York hit Scharnhorst with 14 x 14 inch shells, not one of which penetrated the deck. Helmut Boekhoff again: "the ship was on fire from stem to stern". He had climbed up the main superstructure to the top of the bridge before being thrown into the water as the ship capsized. The Executive Officer, Fregattenkapitan Dominick, was seen be calmly helping seamen on with their life jackets. The Captain, Hintze, gave his life jacket to a sailor who had lost his own. Wilhelm Godde, another survivor, made a point in mentioning that at no time did discipline lapse or panic set in. Both Rear Admiral Bey and the Captain survived the sinking and were seen swimming in the water, but both drowned although Hintze was very close to being rescued by Scorpion. |

Scharnhorst survivors. I would imagine this is a UK image as the survivors were not happy about being in Russia. |

| Out of a ships company of 1900 men, only 36 were rescued! These were taken to Kola and transferred to the Duke of York for shipment to the UK. After a brief moment of panic and visions of Siberia when they were put aboard a soviet tug, they relaxed when it was clear they were not being handed over to the Soviets. They were very well looked after on board the Battleship. Duke of York arrived at Scapa Flow on New Years Day 1944. She received the cheers of all assembled ships companies. An emotional homecoming. Admiral Fraser told his men to celebrate Christmas. Messages of congratulations flooded including the First Lord of the Admiralty, President Roosevelt and even from Marshal Stalin. But it was also a time for reflection. The sailors of the Royal Navy (and the Royal Norwegian Navy) were only too aware that nearly 2000 sailors had gone to their deaths in the bleak waters of the Arctic. An officer on board the Sheffield wrote: "All that is left of a 26,000 ton ship was some 36 survivors. One couldn't help feeling a little sorry for those who had perished. It was a cold dark night, with little chance of survival in those icy waters. However, it might just as easily have been one, or indeed, all of us" |

|

Little exultation was evident aboard the ships that took part in the Battle of The North Cape. It had been too grim for that and, by necessity, remoteness of actions at sea precludes any hate between sailors. This was, of course, countered by an intense pride in what had been achieved, doing what they had been trained for in a ship built for that very purpose. Also consider the possible hundred's of civilian merchantmen whose lives had been spared by the failure of the Scharnhorst to break through to the nearby convoys and by the diligence of men like Burnett, who would not let go. And what of these two convoys that these ships protected so well? RA53a got through to the UK unscathed. Only a single sighting by a solitary Luftwaffe plane indicative that the Germans were even aware of its passing. Convoy JW55b, on its way to Kola had several U boats in contact, but by the 27th this had dwindled to just a single submarine. The others had been called off to go to the battle area to both search for survivors and, as the ULTRA signal inferred, to attack any Royal Naval vessels found nearby. On Dec 29th, the convoy arrived safely at Kola with just one straggler, the "Ocean Gypsy" coming in late, some hours behind. Convoy RA55b left Kola on New Years Eve 1943, consisting of 8 ships and arrived safe and sound at Loch Ewe on 8th Jan 1944. |

Tirpitz |

The sinking of the Scharnhorst had finally eliminated all the surface threats to Arctic convoys, although Tirpitz was still under repairs following damage inflicted during the Royal Navy's X Craft attack. Tirpitz would continue to affect Home Fleet planning throughout the summer of 1944 but would take no further action against the Allies by being sunk at her moorings on 12th November 1944 by bombers of the royal Air force and several 12000 lb "tallboy" bombs, when moored at Tromso. She had been moved there after previous carrier borne air attacks had damaged her. But, her new berth was 200 miles nearer the UK, and within range of the RAF bombers. Strangely, in all the attacks leading up to the sinking of the Tirpitz, not a single Luftwaffe plane sortied against the RAF who enjoyed complete autonomy over the skys of the Norwegian fjords! Captain Parham of HMS Belfast recalled years later that " the best way of remembering that day would be to read the despatches whilst being rocked in a fridge, lit by a single candle, with someone banging on the outside with a hammer". In spite of the awesome firepower from the Duke of York, she did not inflict fatal damage on the Scharnhorst. The general credit for this now lies on the brave destroyer of the Royal Norwegian Navy, the Stord. She made her very courageous attack, closing to within 400 yards of the big guns (one shell would have sunk her) and delivered a torpedo attack which completely changed the picture and course of Battle. |

|

|

Recommendations for gallantry were published with considerable speed. Fraser was awarded the GCB and later, the Order of Suvorov, from Soviet Russia. Burnett got a KGB, Addis of Sheffield, Bain of Norfolk, Parham of Belfast and Russell of Duke of York each received the DSO. Walmley of Saumarez got a bar to his DSC. Fisher of musketeer and Clouston of Scorpion each got the DSC. As stated earlier "Barehand Bates" was awarded the DSC and his two radar ratings, Able Seaman Badkin and Able Seaman Whitton each received a DSM. In the press appeared an epitaph to the Scharnhorst on which the Sunday Times War Correspondent described that it had been "a model operation of its kind, in which all concerned on our side seem to have played their parts with utmost text book correctitude. By comparison with the masterly British performance, the Scharnhorst's conduct seems extraordinarily vacillating and irresolute. She should have been quite strong enough to break through the British cruiser screen and play havoc with the convoy. Yet she waited about three vital hours between two half hearted in ineffective advances, and finally went down with great loss of life without achieving anything at all" Although I am of a military background, 17 years a Tank Regiment soldier, I have never served with the Royal Navy but did put to sea on a calm day, onboard HMS Fearless, off the Dorset coast. After researching the above I cannot fail to believe that the weight of blame for the inexcusable tactics of this most beautiful of ships, the Scharnhorst, must lie on the shoulders of Rear Admiral Bey. As with all "flag ships", the Admiral on board makes the ultimate decision but the views of the ship's Captain (Hintze) should have been taken into account. I have a gut feeling that they were not. I read many years ago of the differences between Captain Lindemann (Bismarck) and the Admiral, where tactical decisions of the Captain's were overruled by the Admiral (and by Berlin). Decisions reached by the on board hierarchy left the British stunned and surprised. The four apparent occasions that the Scharnhorst was "surprised" are already spoken of in this section, couple this with evidence that Scharnhorst knew of the Duke of York's presence via her radar, yet they did not call the gun crews to action stations and "guns were fore and aft" when sighted. The saddest part of all this is the loss of 2000 souls. Although these were sailors at war, it was an unnecessary death - achieving absolutely nothing! The thing that does stand out in my mind is the bravery of all the sailors involved, on both sides. The thoughts of the victorious British sailors were not on celebration but of their near 2000 dead "comrades of the sea" that would not reach home ports again. I see quite clearly that all sailors, of whatever nation, are of a unique fraternity and I salute them - all. Most are brilliantly led, others, just led. The following can be found in amongst other information on: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/wwtwo/scharnhorst_01.shtml |

|

Almost 60 years later (2000), a Norwegian underwater survey vessel searched the 25 square kilometres of the seabed surrounding that official position. However, the wreck wasn't found. In the Public Record Office in London, the actual navigational log of HMS Duke of York Admiral Fraser's flagship, records an entirely different position for the sinking from that shown in the official Dispatches. However, is it any more credible than the official position? None of the logs of the other ships taking part in the battle give any positions for the sinking, but there is a unique method to check the accuracy of the log position. This is a computer driven warship simulator at the Royal Norwegian Navy's Naval Academy in Bergen. It is similar to an aircraft simulator, but with a warship's bridge replacing the flight deck. In order to recreate the battle, the Bergen computers were loaded with navigational data from the log of the flagship, along with her documented performance data. A virtual Battle of North Cape could now be fought. The simulator transforms itself into the bridge of HMS Duke of York as it was at noon on 26 December 1943. At this time, the exact position for HMS Duke of York is precisely recorded in her navigational log. From now till the sinking of Scharnhorst, the simulator will reproduce every movement of HMS Duke of York. Seven hours later, at the climax of the re-fought battle, the virtual Scharnhorst is sunk. The simulator's computers download a different area for the sinking - an area of the seabed approximately 20 sea-miles north of the position given in Fraser's official Dispatches. However, would a search of this new area of seabed be any more fruitful? In September 2000, in an attempt to answer this question, HU Sverdrup II, an underwater research vessel operated by the Norwegian Defence Research Institute, sailed from Hammerfest in arctic Norway. En route to its regular seabed mapping operations, Sverdrup had already surveyed the area indicated by both the simulator and the Duke of York's logbook. Having detected a large object on the seabed, she is now the sonar platform for a joint expedition by the BBC, Norwegian Television (NRK) and the Royal Norwegian Navy. The vessel's multibeam sonar produces an image of two objects, one 170m long, the other 70m long, and positioned at an angle to the first. Is it a wreck and more importantly, is it the wreck of Scharnhorst? The total dimensions are consistent with those of the battle cruiser. However, it could be a geological feature on the seabed. The expedition transferred to the Royal Norwegian Navy's Underwater Recovery Ship, Tyr. Sending down her ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle), part of the mystery is immediately solved. It is a wreck - but is it Scharnhorst? The layout of the surviving weaponry, like torpedo launchers and gun-turrets, leaves no doubt. Seen for the first time in almost 60 years, Scharnhorst's hull lies upside down on the seabed. Her main mast and her rangefinders are the right way up on the seabed some distance away. As is her entire poop deck, with the stern anchor still in place. The hull shows extensive damage from both armour-piercing shells and torpedoes. HMS Duke of York fired 80 broadsides; and the Allied ships fired a total of 2,195 shells during the engagement. Some 55 torpedoes were launched at Scharnhorst, and 11 are believed to have found their target. There is now an explanation of why she sank so suddenly. A massive internal explosion - probably in an ammunition magazine below a forward gun turret, had blown off her bow. The entire bow section remains together as a mass of wreckage and armour, but separated from the main wreck. Of the Scharnhorst's total crew of 1,968 men, only 36 survived. Many of those had been ordered to abandon ship, but were left behind in the water when the Allied ships quickly departed the area. Remembering the incident, Rex Chard, Navigating Officer on one of the destroyers, remarked, 'in sea-warfare one is always very sorry for the sailors. It's the ships you're after - not the men. It could have been you.' |

|

From Len Williams, an email, Feb 05 My grandfather was a guard at a prisoner of war camp in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada, during WWII. In the camp was a member of the crew of the Scharnhorst, who also happened to be an excellent wood carver and model maker. This crew member had spent his time of incarceration building a beautiful wooden model of the Scharnhorst from memory. It's a wonderful thing and expertly crafted. Canadian winters can get quite cold and according to the story, my grandfather exchanged one of his government-issued greatcoats for the wooden model. The Scharnhorst replica was placed in a glass and wooden case in the late 40s and resided at my parents' home for many years. The model will soon come to me in the distribution of my parents effects and I would like, if possible, to track down the name of the German crew member who carved the ship. Do you have any idea where I might start to search for this information? It would be wonderful to have the full history of the model to pass along to my relatives. Of course, I could kick myself for not quizzing my grandfather on this before he passed away, but as a young boy my attention wasn't on the history of things, merely that I always loved the model in the glass case. I currently live in Clearwater, Florida, USA, and will be travelling home to Canada to retrieve the ship soon. Sincerely, Len Williams. |

Rawalpindi Memorial on Liverpool's Pier Head

|

|

The above was scanned to me from

Peter Walton, whose neighbour served aboard HMS Jamaica and who sadly died, leaving Peter with this (possible) original. |

|

|

Duke of York in heavy arctic seas |

|

http://youtu.be/XmtpzT3zGBY Scharnhorst (Capital ship preamble)

![]()

Buy My WW2 Book here - Scharnhorst is featured