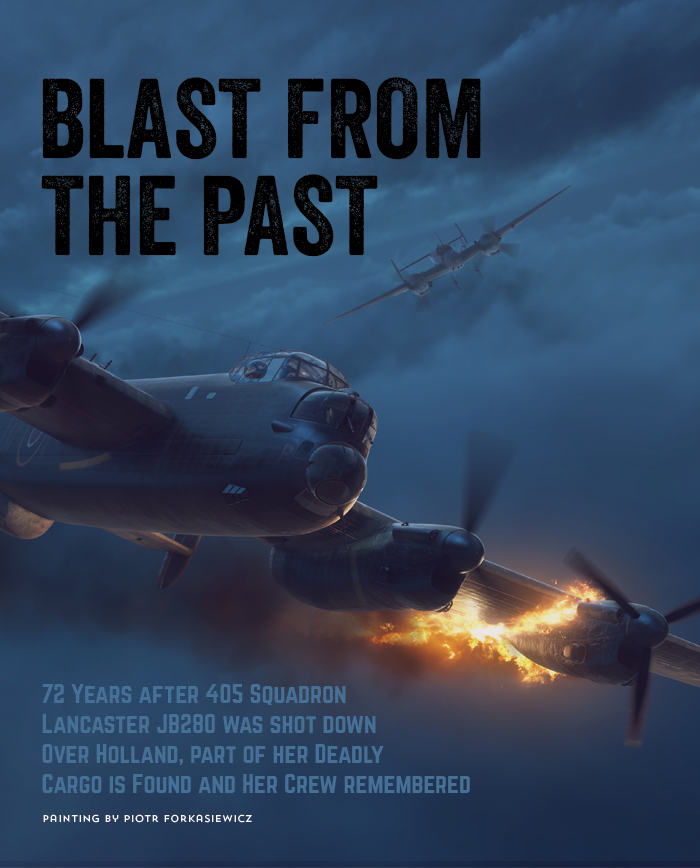

Avro Lancaster JB 280

Created March 28th 2016

By Dave O’Malley with Rob Wethly

reprinted from

http://www.vintagewings.ca/en-ca/home.aspx

with permission

|

|

|

All day long on the first of January 1944, the

weather at RAF Gransden Lodge and throughout most of Cambridgeshire was

grey and cloudy with typical English mists drifting across the airfield.

The winds were moderate and out of the west. The Lancaster bomber crews

of No. 405 Pathfinder Squadron stationed at Gransden Lodge were stood

down for the day, some recouping from New Year’s Eve revelry. At a

briefing they learned that there would be an operation that night, but

take-offs wouldn’t begin until after midnight. The target was Berlin.

They had several hours to endure the stress of inactivity, but once they

had strapped in, they would settle down. They were Pathfinders after

all, elite bomber crews, the best of the best, who would lead the Bomber

Stream to the target and mark it by accurate bombing, the kind of

accuracy the Pathfinders were trained for and capable of. Flying Officer Tom Donnelly and his crew were ready for the task. Donnelly himself was a veteran on his second tour of operations. Surviving one tour was an accomplishment, beating odds that were well stacked against making it home alive. His bomb aimer, Sergeant William L.T. Clark, was feeling good. He had spent the previous evening in the company of his brother Jack who was also in the RCAF, reminiscing about life back in Vancouver and getting home after the war. He was happy to be in Donnelly’s crew—the skipper was experienced and fun to be around. He wore the ribbon of the Distinguished Flying Medal on his battle dress jacket and the winged “O” pin of an airman who had completed a full tour already. It gave Clark a sense of confidence seeing that ribbon, but looking at that pin, he had to wonder when Donnelly’s luck would run out. Luck was such a huge part of it. The 405 Pathfinder Squadron operations and

planning room at RAF Gransden Lodge, about 16 kilometres west of

Cambridge, England. In this busy and smoke-filled room, missions were

planned down to the smallest detail, taking into account all variables

such as fuel, daily signals, meteorology, intelligence, German defences

and bomb fusing times. After planning, the squadron assembled for a

briefing before being driven to their aircraft. Photo: RCAF

Always, when the target was Berlin, the boys got

quiet and moody. Stress was hard to hide. Berlin was a 1,900 kilometre

round trip in the proximity of hundreds of other bombers in total

darkness, across flak concentrations and the deadly hunting grounds of

Luftwaffe night fighters. It was reasonable for man to be worried.

At around midnight the signal flare went up and

the twelve Lancasters of 405 Squadron RCAF moved out to the runway in

the dark. Donnelly and his boys were in Lancaster LQ-K, RAF serial

number JB280. The Lancaster had survived three and a half months of

operations with 405 since its delivery date on the 16th of September

1943, a week after it rolled out of the factory. In her belly, LQ-K

carried a relatively light load, for they were flying a long way

tonight—four 1,000 lb. bombs and one 4,000 lb. bomb called a “cookie.”

This type of ordnance was designed for the destruction of industrial

centres. At 23 minutes past midnight, in the very early hours of the

second day of 1944, Donnelly, Bomb Aimer William Clark, Navigator Jerry

Salaba, Flight Engineer Leslie Miller, Radio Operator Brian West, and

Air Gunners Ron Zimmer and Ron Watts lifted off the active runway in

darkness and radio silence, climbing and circling until the squadron was

formed and headed to join the Bomber Stream where a total of 421

Lancasters coming from all over southern England would join together in

the dark of night and head toward Berlin—1,684 Merlin engines delivering

the whirlwind of vengeance, almost 3,000 young men huddled in darkness,

cold and menace, surrounded by fear, powered by courage and love of

their brothers. Though there were thousands of men up there in the night

sky, each man felt alone—dry mouth, high pitched voice, darting eyes,

forced jocularity. Somewhere near the coast of England they joined

the stream and headed across the North Sea. With them was a small group

of fifteen Bomber Command Mosquitos that would attempt a diversionary

attack on Hamburg. It didn’t work. The night fighters’ dispatchers were

not fooled this night. As Donnelly and his crew settled down over the

North Sea for the long flight across Holland and Germany, night fighters

were rising to meet the stream. These highly experienced Luftwaffe crews

flying night fighting variants of the Junkers Ju 88 and Messerschmitt Bf

110 were the true scourge of Bomber Command. Unlike searchlights and

flak, which to some extent could be avoided, night fighters were unseen,

vicious and above all, unpredictable. The entire crew relied on the

sharp eyes and night vision of their two air gunners—Watts in the rear

turret and Zimmer in the top turret. Watts was 33 years old, young by

today’s standards, but ancient in a squadron of teenage boys and twenty

somethings. Zimmer had just turned 20 years olf. As they crossed the coast of Holland, they

avoided the heaviest concentrations of flak and droned on through the

night towards their destiny—alone among 420 other crews. Around 2 AM,

Salaba would have called Donnelly on the intercom to let him know the

Dutch-German border was just ahead. In a few minutes they would be over

the homeland of the enemy. Here they would face the most determined of

defences. About the same time as Salaba updated his

skipper, Luftwaffe ground radars were vectoring a Messerschmitt Bf 110

night fighter into the Bomber Stream close to LQ-K. It was pitch dark at

20,000 feet, but a trained night fighter pilot could spot the exhaust

flames and sullen dark shapes against a murky black sky. The pilot of

the all-black Messerschmitt was Leutnant Friedrich Potthast, known as

“Fritz” to his pals. With him in the cockpit were two others, a rear

gunner and a radio operator in contact with the ground. Potthast had

been a fighter pilot since near the beginning of the war, but he had

only three other kills to show for all that fighting, two Blenheims on

19 August 1941 in particular. But tonight, he would begin a streak that

would net him 8 more night kills before his death five months later.

Night fighting was proving to be his forte. |

|

|

Luftwaffe ground crew refuel a Messerschmitt Bf

110 night fighter of the famous Nachtjagdgeschwader 1. Of all the night

fighter squadrons in the Luftwaffe, NJG-1 was the most successful,

shooting down an astonishing 2,311 enemy aircraft. The unit paid a heavy

price for this reputation with 676 aircrew killed in action. The high

number of victories by NJG-1 was testimony to the terrible dangers faced

by Bomber Command aircrews every night. The unit’s emblem was a diving

white falcon with a red lightning bolt striking a map of Great Britain.

The pilot of the night fighter that shot down JB280 was Leutnant

Friedrich “Fritz” Potthast, an ace with 11 kills to his name (8 at night

and 3 by day) when he was shot down nearly five months later on the

night of 21–22 May 1944 near Sourbrodt in eastern Belgium. Lancaster

JB280 was his fourth kill. Night fighter Bf 110s had a crew of

three—pilot, rear gunner and radio (radar) operator. It is not known who

was with him the night he shot down the Donnelly crew, but on the May

night he died, his two crew members were Feldwebel (Sergeant) Albert

Kunz and Obergefreiter (Aircraftman) Hans Lautenbacher.

Photo via Bundesarchiv |

|

We will never know the full details of what

happened over the next ten minutes in the night sky near the

Dutch-German border, but at approximately 2:10 AM, the remains of

Lancaster JB280 and its crew came shrieking, flaming and tumbling out of

the night sky near the small town of Nieuw-Schoonebeek, slamming into

the ground not 200 metres from the German border. The wreckage contained

the bomb load of Donnelly’s JB280, but likely centrifugal forces had

sent the five bombs off on their own trajectories [photos of the

fuselage section on the ground do not show the kind of damage one would

expect if the bombs exploded while still attached.]

One can imagine the spectacular and life-changing drama of a

four-engine bomber falling in flames from the night sky—the

shrieking wind, the rending of metal, the ultimate devastating

impact with the ground. Today, such a powerful scene would be world

news, but on the night of 1–2 January, it happened 28 times along

the flight path of the Bomber Stream in and out of Berlin. The 28

Lancasters held 196 young men. Night after night, month after month,

year after year, metal and youth would be broken against the

obdurate ground of Europe. While it became commonplace in a broad

sense, it was nonetheless a traumatic event for local witnesses,

causing in many cases injury and death, and in all cases powerful

emotions and haunting memories for the rest of their lives.

|

|

|

Dutch citizens come by to look at the wrecked

fuselage of Lancaster JB280 lying in a farm field near the town of

Nieuw-Schoonebeek. The framework at the right of the fuselage is the

floor above the bomb bay with doors gone. The faring around the hole in

the centre of the fuselage section is for the H2S Radar, the antenna

housing having been destroyed. These wrecks would soon be loaded on to

trucks and driven away to be melted down for German production. Photo

via drentheindeoorlog.nl |

|

The same Lancaster JB280 fuselage section as

above, but viewed from the other (top) side. We can clearly make out the

letters LQ-K. The Fraser-Nash power-operated dorsal turret glazing

framework lies crushed at centre. Photo via drentheindeoorlog.nl |

|

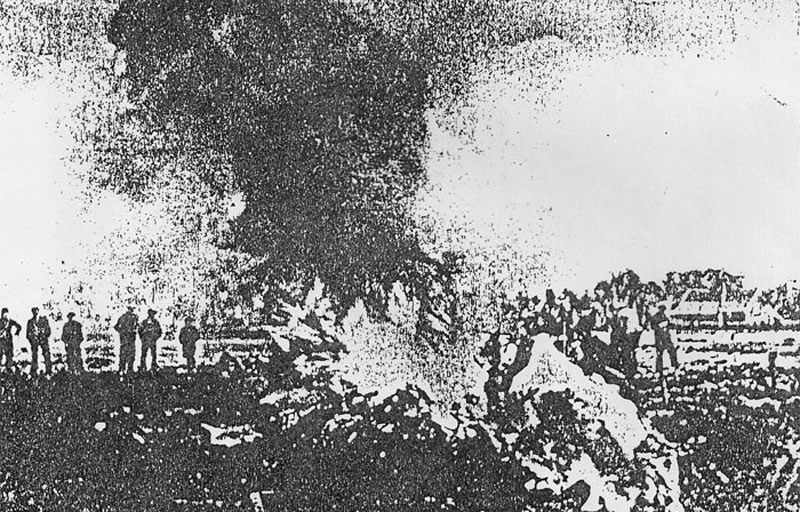

A photocopy of a

photograph taken the morning after the crash. Clearly, there was nothing

to do but watch the fire burn itself out. Image via Rob Wethly |

|

As the wreckage of JB280 and her seven young

crew members lay burning and smoking on Lambers’ farm, the Bomber

Stream, heard but unseen in the night sky, continued it relentless and

harrowing journey into the heart of Germany. Donnelly’s demise was

possibly witnessed by others in the stream—tracers in the distance,

flames blowtorching in an invisible hurricane, silent screams—but none

could know who it was. Gunners and pilots of other Lancasters could only

glance at the drama and perhaps inform their crews (There goes

another—bloody hell!) but they had a job to do. If anything, the arcing

smear of flame in the distant night sky that was once a Lancaster was a

warning that wolves were in their midst. Men turned away from the death

and concentrated on watching their own immediate sky. Terrible… but

lucky us. Of the night’s work by Bomber Command, the RCAF

post war journal called The RCAF Overseas had this to say of the night:

“January 1st, 1944, marked the opening of the second year of operations

of the R.C.A.F. Bomber Group, a component of Bomber Command. The twelve

months had seen a notable development in the operational efficiency of

the squadrons so that with the opening days of the New Year, members of

the Group could look forward in quiet confidence to a period of

increasing responsibility. In the year to come, the Group, its growing

pains past and forgotten, was to come into its own as one of the most

efficient fighting units in all the United Nations Air Forces. Our Lancasters, almost without exception, found

complete cloud cover from base to target and back when they attacked

Berlin on New Year’s night [actually they took off after midnight—on

January 2nd]. For the most part they stooged along between cloud layers

and as a result were little bothered by searchlights except when the

clouds cleared momentarily to allow the Cologne-Kassel-Frankfurt band to

break through. Night fighters were not particularly in evidence and flak

was never troublesome, yet the raid was far from being an outstanding

success. The target area was completely covered, the tops

of the clouds varying from 10 to 18,000, and many of our kites found a

further heavy layer above that. Furthermore, the pathfinders were having

an off night and their work was erratic and scattered. As a result, the

host of bombers, averaging 12 per minute over the target, returned to

their various bases with little concrete knowledge as to whether the

hundreds of tons dropped had really achieved the desired result, but

quite convinced in their own minds that the raid, considered as

saturation bombing, had been largely abortive. Nevertheless, such a

weight of bombs dropped on a city like Berlin must have done very

considerable damage and the effort therefore was not entirely in vain.

F/O T.H. Donnelly, D.F.M., on his second tour of operations, was lost on

this raid with his crew, F/O A.J. Salaba, FS W.L.J. Clarke and Sgts.

B.S.J. West, R.E. Watts, R. Zimmer and L.G.R. Miller.” |

|

|

As the sun came up over Nieuw-Schoonebeek, on

that terrible Sunday morning, there was no thought of going to church…

at least not yet. In the thin light of winter, townsfolk set to the grim

and fruitless task of searching for survivors and policing up the broken

youth of the Royal Canadian Air Force. According to the official report

filed by local military police chief Hendrik Rinsma, three of the bodies

were found intact, two others were in pieces scattered about and God

knows how the other two were found. It was clear from the craters, or

perhaps detonations, that four bombs had exploded. They had no way of

knowing how many bombs the aircraft had been carrying. They were buried three days later in the

Schoonebeek General Cemetery where they remain today. Some time later

after their identities were known, white crosses were erected with their

names, ranks and service numbers painted on them. As tragic and

traumatic as the destruction of JB280 and her crew was, it was not much

more than a brief side note in the litany of death and suffering that

was the Second World War, one of 28 such events to happen on that night

alone in that sector. It warranted but three typewritten lines in the

405 Squadron Operational Record Book for January 1944. It was imperative

that Wing Commander Reg Lane and his 405 Squadron move forward and put

the horrors they witnessed every night behind them. There would be time

to weep after victory. While Canadians have let the seventy-two years of intervening time fade the memories of all of our lost youth of the Second World War, the Dutch have most definitely not. Perhaps it is gratitude. Perhaps it is the fact of the flaming Lancasters full of courage that came to dash themselves upon their soil. Perhaps it is the memory of their terrible suffering at the hands of the Nazis and the rushing elation of liberation that drives them to remember. I’ve said it many times before and I will say it again, the Dutch are better at remembering Canada’s fallen than Canadians. While we should be grateful, we should also be ashamed. |

|

The story of JB280 and the Donnelly crew did not end with their burial.

Throughout the seven decades since that terrible, but all-too-common,

event in the opening hours of 1944, the townspeople of Oud-Schoonebeek

have tended the graves and paid homage to the seven fallen men of JB280

as well as several other young men whose lives came to an end along with

their aircraft near Schoonebeek. Like many village cemeteries throughout

Europe, the original white crosses have been replaced by the now

tragically ubiquitous granite tablet headstones of the Commonwealth War

Graves Commission. Like many such beautiful places throughout Europe,

the headstones of Donnelly’s crew have been meticulously tended and

loved by the people of Nieuw-Schoonebeek. Here, on Christmas Eve, 2015,

the members of Study Group Air War Drenthe (SLO Drenthe), a society

dedicated to the preservation of the stories of men like those aboard

JB280 and their brethren, light votive lights at each of the fallen’s

headstone. Photo via Rob Wethly |

|

|

72 years later — JB280 delivers her

final payload |

|

|

There is much more to see on the following

web link. Photographs of crew, graves, finds in the fields etc Blast from the Past |

|

Memorial in Royal Sutton Coldfield Park |

|

Other sites of interest

http://www.lincsaviation.co.uk/history/history-of-the-lancaster.htm/a>

hhttp://www.challoner.com/aviation/pix/65-6.html

http://www.kiwiaircraftimages.com/lanc.html>

http://www.military.cz/british/air/war/bomber/lancaster/lancaster_en.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avro_Lancaster

http://www.lancasterfm159.freeservers.com/

http://www.britannica.com/normandy/articles/Lancaster.html

http://www.nicks-cave.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/jane/lancs1b.htm

and of course, the modellers delight:

http://www.turbosquid.com/FullPreview/Index.cfm/ID/145989/intType/7/stgCHSource/Popular

http://www.canadianflight.org/giftshop/h-033.htm

http://web.inetba.com/aircraftmodelscorp/item7372.ctlg

http://www.aikensairplanes.com/corgi/c32608.htm

http://www.asrmcs-club.com/ - Air Sea Rescue