All my other Sea Pages

By Mike Kemble - Created June 2002 Updated: 17 april 2013

|

|

Memorial to the thousands of sailors of the Merchant Navy who died at Sea in WW2, Pier Head, Liverpool |

|

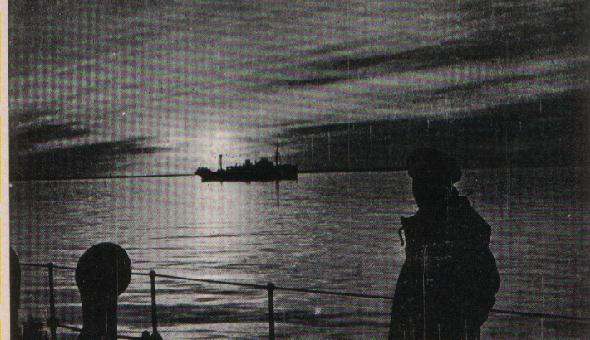

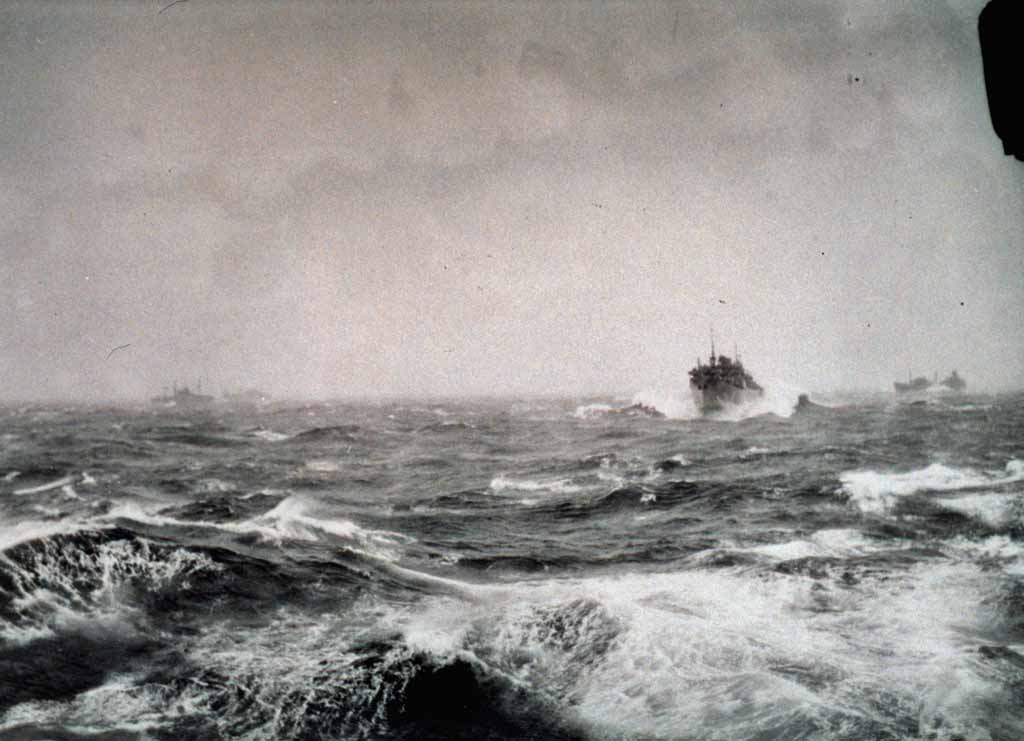

What a miserable, rotten hopeless life . . . an Atlantic so rough it seems impossible that we can continue to take this unending pounding and still remain in one piece . . . hanging onto a convoy is a full-time job . . . the crew in almost a stupor from the nightmareishness of it all . . . and still we go on hour after hour. So described a sailor aboard an Atlantic Convoy escort in World War 2. Frank Curry of the Royal Canadian Navy wrote those words in his diary aboard a corvette in 1941, during the Battle of the Atlantic, a battle that would be called the longest in history. |

|

| "if all the supplies carried by just one average sized Atlantic convoy (35 ships) were gathered together they would fill a line of ten ton trucks spaced 50 yards apart which would stretch from Inverness to Southampton via Carlisle" |

|

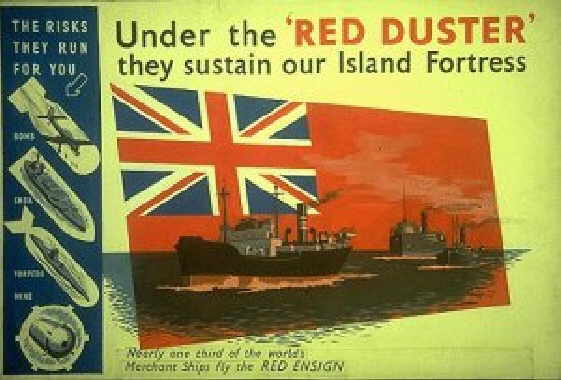

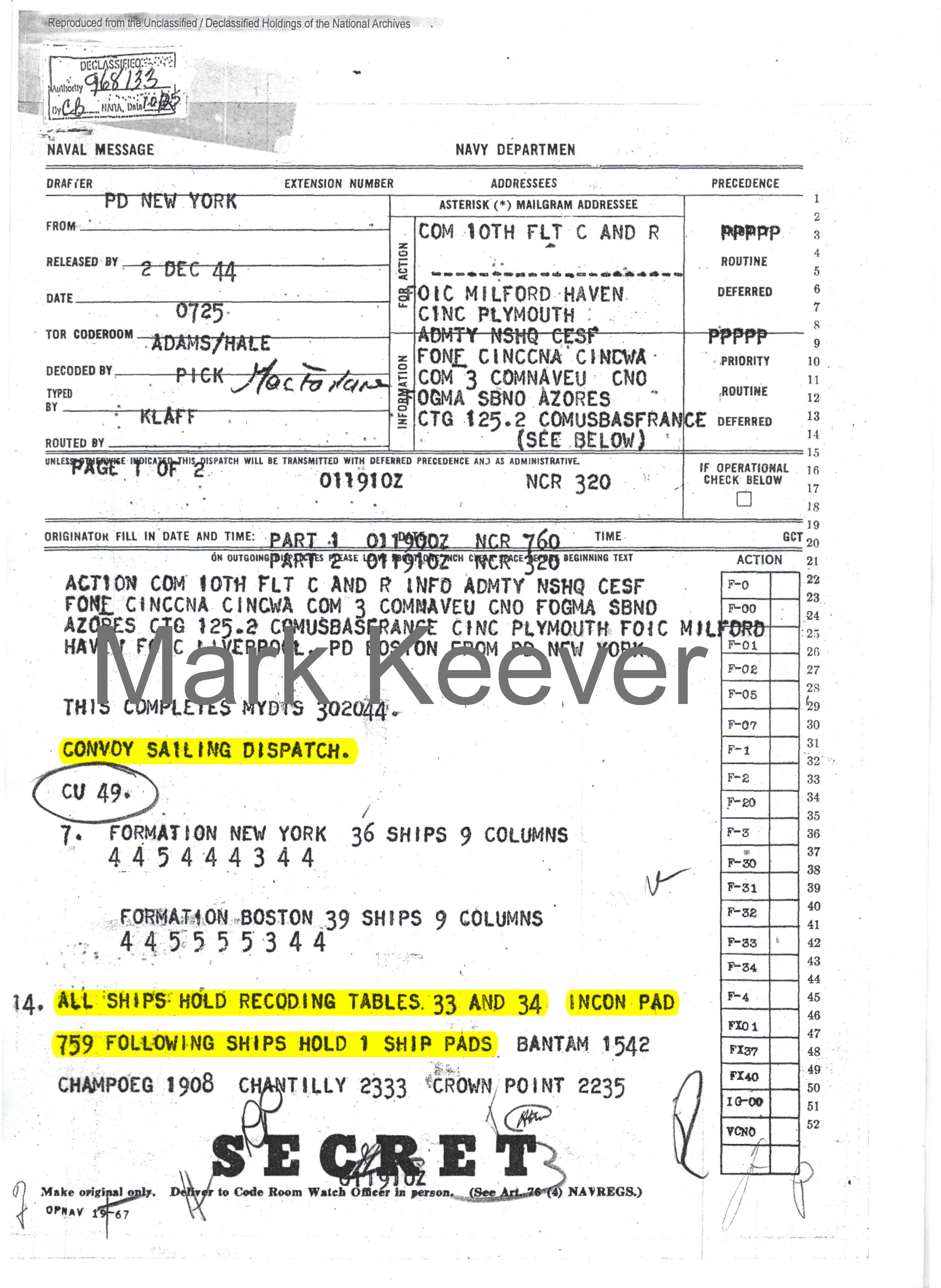

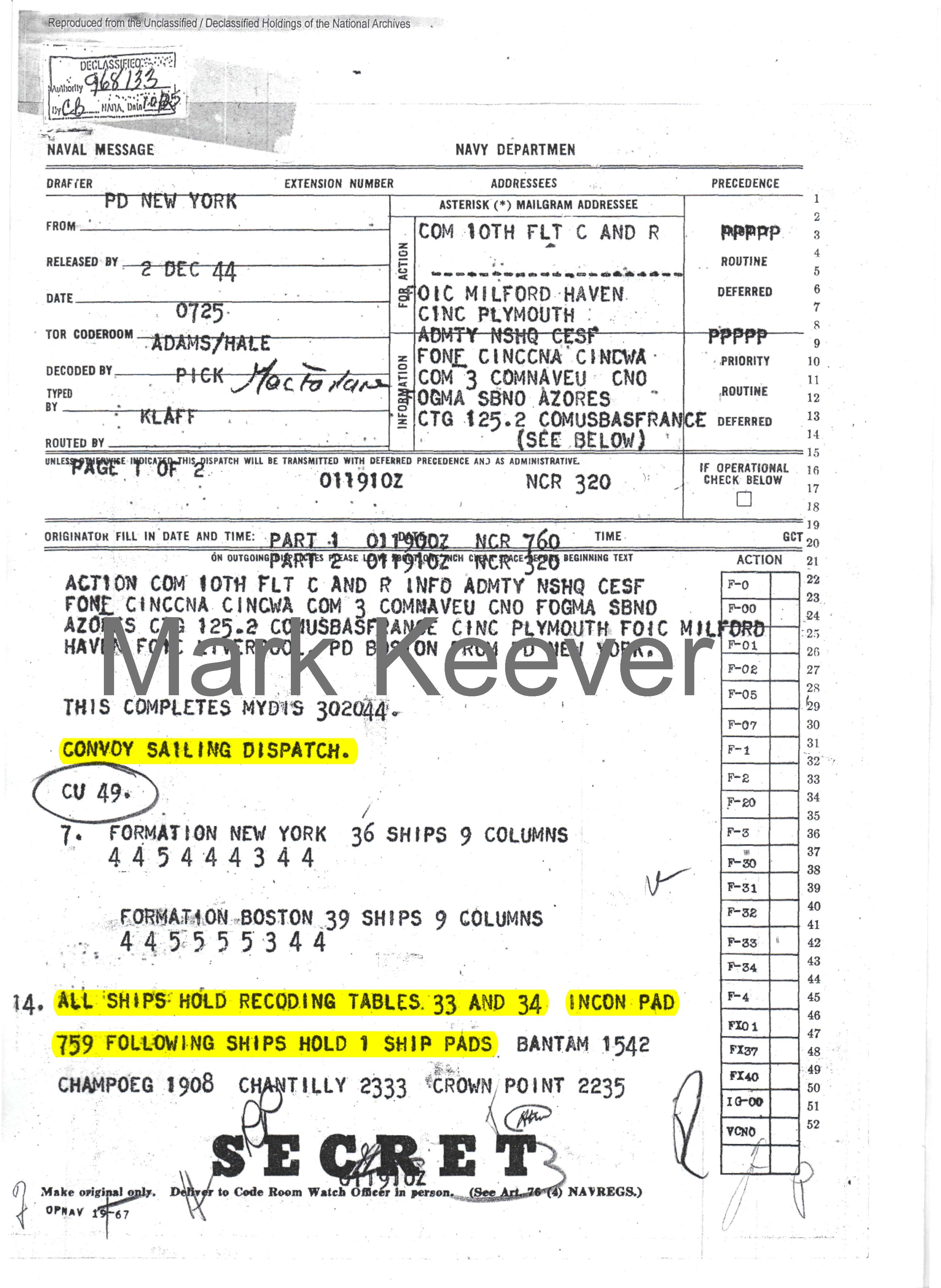

As the poster denotes, during World War 2 nearly one third of the worlds merchant fleet were British and these civilians ran the gauntlet of U Boats and, in the beginning, surface raiders like Bismarck, every trip across the Atlantic and beyond. The Battle of the Atlantic was considered won by the Allies by 1943, although it lasted until the end of the War on 8th May 1945. It began on September 3rd 1939 when the Montreal bound passenger ship SS Athenia was sunk by a U Boat west of Ireland. Of 1400 passengers and crew, 118 died. The tide finally turned in the middle of 1943 with the provision of better training, air cover, special intelligence and better equipment. The Special Intelligence mainly comprised of the breaking of the German Naval Codes with Bletchley Park and Enigma. Over 30,000 Seamen from the British Merchant Navy were lost between 1939-1945. On September 3rd 1939 a few hours after war had been declared against Germany the first shipping casualty occurred in the sinking of the unarmed Donaldson Line passenger ship Athenia (see below) with the loss of 112 passengers and crew. While Britain was living through the “Phoney War” between September 1939 to May 1940, 177 British Merchant ships alone were sunk and for almost six years after there was barely a day went by without the loss of merchant shipping and their civilian crews. |

On all the oceans white

caps flow, you do not see crosses row on row, |

SS Athenia Sinking -Click on the image to visit my Athenia Page |

|

In 1942 Ivor Halstead wrote a book entitled "Heroes of the Atlantic" which was published in the USA due to obvious restrictions in the UK of raw materials. He wrote "On two Sundays towards the end of January, I combed my six Sunday newspapers and failed to find a single word about the Merchant Navy". The usual Forces all had mentions from the newspapers specialist writers, politicians and diplomats "got a good show" and generous space devoted to the "preservation of Malcolm MacDonald who, as Dominions Secretary, shared with the late Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the tragic folly of leaving our vital Atlantic naval bases in the hands of a hostile Ireland". I obtained a first edition of this book, from a bookstore in St Petersburg, Florida via http://www.abebooks.co.uk for a very reasonable price. It goes on "but the lives of the brave men whose perilous work was given a sharper edge of danger by these guilty leaders there was no word". In the early days of February, Lord Beaverbrook warned us of "the springtime danger to our north-western approaches, the sea highways from the USA and Canada". |

Halifax Convoys assemble Convoy OB190 |

The following two images are copyright and cannot be reproduced |

|

|

One of the vessels named above is this one, the Esso Hartford |

|

| The SS Esso Hartford was built in 1942 by the Bethlehem-Sparrows Point Shipyard, Inc., at Sparrows Point, Md. She is a sistership of the Esso Annapolis (second vessel so named) and the Dartmouth. Another sistership, the Esso Harrisburg, was lost on July 6, 1944. A single-screw vessel of 16,585 deadweight tons capacity on international summer draft of 30 feet, 1/8 inch, the Esso Hartford has an overall length of 501 feet, 7 3/4 inches, a length between perpendiculars of 487 feet, 6 inches, a moulded breadth of 68 feet, and a depth' moulded of 37 feet. With a cargo carrying capacity of 131,136 barrels, the Esso Hartford has an assigned pumping rate of 6,000 barrels an hour. Her turbine engine, supplied with steam by two water-tube boilers, develops 7,700 shaft horsepower and gives her a classification certified speed of 15 knots. She was a hero of many transatlantic trips taking urgent fuel supplies to the UK. |

|

|

Convoy under way, note Escort Carrier in foreground |

At the same time Hitler made a speech about fantastic figures of what he called "recent Atlantic sinkings". He also promised an onslaught from hundreds of new U Boats that would strangle Britain. If we go back even further, to World War 1, and by the severe winter of 1916/1917 Germany was almost on her knees and starving. Von Tirpitz asked von Hindenburg for permission to "ignore all the recognised rules of submarine warfare" in order to proceed with "unrestricted and unannounced attacks on allied ships ", within no time at all this had the effect of devastating Britain's Merchant Navy and losses soared daily and it was Britain's turn to be almost starved out of the war, so much so that certain leaders were privately considering how best to end the war as soon as possible. It was on 1st February 1917 that "Spurlos Versenkt", (unrestricted submarine warfare) was officially begun by Germany. Already Germany had shown, in the second battle of Ypres, with the use of poison gas, that they would go to any length to ensure victory, illegal or otherwise. To be fair, some humanitarians in Germany voiced opposition, but were overcome and Hindenburg gave his permission. Early success of the ruthless German tactics became evident. In the first 3 months 1000 allied ships had been destroyed. 3 out of every 4 of Allied ships fell victim to torpedo, guns and mines of the U boat. By April 1917 the fugire reached the terrifying total of 849,000 tons, representing 423 vessels. However, a man called Commander Reginald Henderson convinced Britain that the answer lay in the convoy system where the lifeline to Britain's ports was kept open with escorted merchantmen to and from harbours. He was not heard at first, being overlooked as the "powers" were not impressed. However, his plans came to the attention of Lloyd George who liked the plan. This plan was to assemble 30 or 40 merchantmen at a rendezvous near their port of loading, take them to sea under cruiser protection and ESCORT them through known submarine infested waters. To the immense relief of everyone the convoy system was the complete answer and its effect was almost instantaneous. The curves on the Ships sunk took a dramatic dive. Of 149 ships that sailed between 2 July and 10 October 1917, only 2 were sunk, being stragglers that failed to keep within the convoys. By the end of WW1, in Nov 1918, of 607 homebound convoys only 118 total ships lost or 0.7%. The history of the British Isles is based upon our successful deployment of both Royal Navy and Merchant Navy around, not only our shores, but all over the world. From the inception of a "royal navy" with King Alfred, through the heady anti Spaniard days of Queen Elizabeth 1; her Admiral's, Frobisher, Hawkins, Drake and then from Nelson against Napoleon right up to the end of World War 2. Our ships have born the brunt of every successful defence of our islands and the Merchant Navy have been the means by which we have obtained the supplies to not only survive, but also win. And yet we still did not afford the men of the Red Duster; the red ensign, the respect and recording that history demands. After World War 1 the merchantman was soon forgotten, again, in the greater scheme of things. And between the wars, depression of the 30s saw hundreds of ships laid up, no use to anyone, no cargo to carry, and as a consequence, no crews to man them. Ivor Halstead again: "But, from the action of war came the reaction of peace, and in the long years of that costly reaction the personnel of the Merchant Navy were, officially, almost forgotten. Neglect led to the scrapping of hundreds of ships and the throwing of thousands of Merchant Navy men on to the scrap-heap with them. Those of us who used to make journeys about the mouth of the Thames and the Medway a few years after the guns of World War Number One had ceased to bark remember the sad dead fleets of iron merchantmen huddled together in dozens, their plates and cables rusting, their fine engines falling into decay, wasting there, a fitting symbol of the paralysis come upon the nation’s political and industrial leaders. At one day all our lives, all our hopes, rested on the courage and loyalty of our merchant seamen—and we praised them. At a later day we were safe, because they had made us so—and we forgot them. The Merchant Navy is our life-line in peace as in war. Successive peace-time Governments ignored the vital truth. Shipyards were stripped of labour because there was less and less work for the men to do and a belated subsidy to tramp shipping was not enough. Nobody would face the fact that war was coming and that everything that would float would be useful and valuable then. For every new ton of shipping two old tons must be scrapped, that was the order. Thus, while 200,000 tons of tramp shipping was built, twice that amount was broken up, most of it British and some of it on the register of countries who are now our allies. There would have been something like 2,000,000 tons more shipping at our disposal on the outbreak of war but for this act of Governmental folly. There was a “too-late” attempt to recover in the spring of 1939. Building was encouraged and scrapping abolished, but by this time thousands of shipyard workers as well as merchant seamen had taken on other employment, so that we started off with ~ grave shortage of both ships and men." This was written, I remind you, in 1942. The main part of the Battle of the Atlantic had yet to be faced. |

|

| Martin Middlebrook in "Convoy" writes that "there was no guaranteed employment; a man signed articles for the one round voyage and was not automatically re-employed for the next, although the better class companies kept what was known as a "following" of carefully chosen, reliable men that it would employ more or less permanently. |

|

The Threat |

|

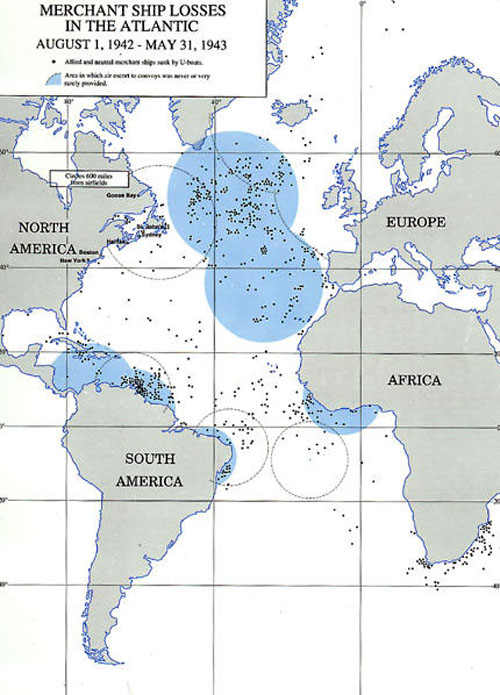

German Submarines, the U Boats were the main threat to merchant and naval vessels. They were capable of operating for up to three months away from port and operated, on the surface, with diesel engines and underwater with battery powered motors. These electric motors had to be recharged by operating the diesel engines, thus having to surface. When the Schnorkel was invented, the U Boats could recharge their batteries underwater by the use of the diesel engine which breathed through this schnorkel. Each U Boat carried up to 21 torpedoes and could also be used for laying mines. A U Boat could submerge in approximately 30 seconds. In one month alone, June of 1941, U Boats accounted for over 500,000 tons of Allied shipping - although, a big a threat as they were, the U Boats only accounted for about 1% of the shipping crossing the Atlantic. The U Boats strike rate improved somewhat with the invention of the acoustic torpedo which could home in on the propellers of the target ship. In 1939, 27 U Boats were at sea at the outset of World War 2; this had increased, despite incredible losses, to 463 by March 1945. |

|

|

The above

map shows where the location of each sinking took place with the dates

above. The Blue circular regions are |

| Outline |

| The Headquarters of the Western Approaches were at Derby House Liverpool; the basements, which are open to the public nowadays. It was from these cellars that the Battle of the Atlantic was waged and, eventually, won. Admiral Sir Max Horton, the C in C Western Approaches conducted Britain's very battle for survival from here. He was assisted by heroic sailors from all over the world who took their lives in their hands every time they left port - many thousands never to return. Many of these sailors were torpedoed, rescued and torpedoed again on the same convoy. Royal Naval Officers such as Captain F.J. "Johnnie" Walker led Black Swan Class Sloops into the Atlantic, independent of convoy duties, to specifically hunt and destroy U boats - with phenomenal success - effectively driving the U boat away from convoy attack by mid 1943. Captain Johnnie Walker has his own pages on my domain and one of his ships, HMS Kite, has its own pages, describing its sad, and unnecessary, fate. |

|

|

| Britain's Objectives |

| The first objective was the defence of the trade routes and convoy organisation and escort, particularly to and from Britain. Until May 1940 the main threat were U Boats in the North Sea and the South Western Approaches. For a few months 2 pocket Battleships posed the main danger in the North Atlantic. Convoys were coded thus: OA: From Thames via English channel. OB: From Liverpool through the Irish Sea. Later on in September 1940 convoys left Freetown, Sierra Leone (SL); Halifax, Nova Scotia (HX) and Gibraltar (HG) all bound for the UK. In the North Atlantic anti sub escorts went out 200 miles west of Ireland and to the middle of the Bay of Biscay. From Halifax, Canadian warships provided cover out to 200 miles. Occasionally Cruisers and Armed Merchantmen took over as Ocean Escorts. Particularly fast or slow shipping sailed independently as did many hundreds of other vessels scattered around the rest of the worlds oceans. Almost all of the war, it was these independently routed ships that suffered mostly from surface raiders, submarines and aircraft of the Axis Forces. |

Convoy at "HX" |

|

The second objective was detection and destruction of Enemy surface raiders and submarines. Patrols are carried out by RAF Coastal Command in the North Sea and by British submarines off southwest Norway and German North Sea bases. RAF Bomber Command prepare to bomb German warships in their bases. Anti submarine patrols were conducted by the Fleet Air Arm in the Western Approaches. The third objective was to blockade German ports and exercise contraband control. As German shipping tried to reach home or neutral ports the Home Fleet sailed into the North Sea and the waters between Scotland, Norway and Iceland. The Northern Patrol consisting of mainly old cruisers, and later Armed Merchantmen, had the unenviable task of patrolling between Shetlands and Iceland. British and French warships, patrolled the North and South Atlantic. Closer to the German mainland Royal Naval destroyers laid mines at the entrances to ports. |

|

|

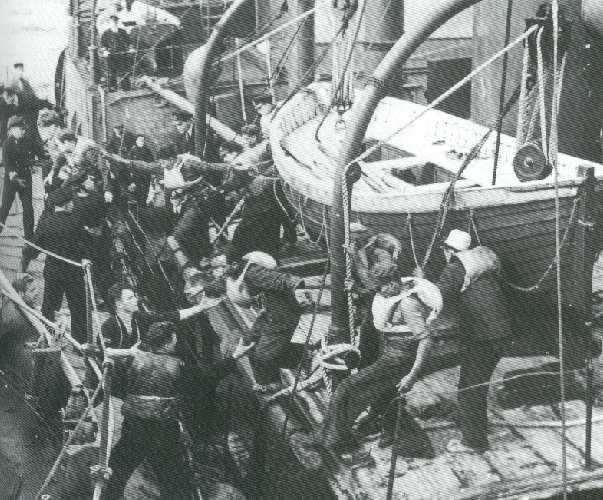

Objective four was the defence of our own coastline. Right through until May 1940 U-boats operated around the coasts of Britain and in the North Sea. Scotland's Moray Firth was often a focus for their activities. They attacked with both torpedoes and magnetic mines. Mines were also laid by surface ships and aircraft. British East Coast convoys (FN/FS) commenced between the Thames Estuary and the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Southend-on-Sea, the Thames peacetime seaside resort, sees over 2,000 convoys arrive and depart in the course of the war. Defensive mine laying began with an anti-U-boat barrier in the English Channel across the Straits of Dover, followed by an East Coast barrier to protect coastal convoy routes. The fifth objective was to escort troops to France and between Britain, the Dominions and other areas under Allied control. An immediate start was made transporting the British Expeditionary Force to France. By the end of 1939 the first Canadian troops had arrived in Britain, and by early 1940 Australian, Indian and New Zealand forces were on their way to Egypt and the Middle East. Troop convoys were always heavily escorted, and the Dominion Navies played an important part in protecting the men as they left their home shores. Australian and New Zealand cruisers were particularly active in the Indian Ocean. Some 35000 merchant seamen lost their lives during the war. The British lost 2,426 ships covering a total tonnage of 11,331,933. It is worth noting that the U Boat losses covered some 30,000 - three quarters of their strength. A casualty rate on board British ships of 85%. 5000 merchant sailors were taken prisoner. British ships employed merchant crews from all over the Empire. Some 27% were Chinese and Indian whilst 5% were Arabs, West Africans (Lascars) or West Indians living in the UK in ports such as Liverpool, South Shields and Cardiff. However deadly the U Boat threat, they only succeeded on sinking 1% of the ships that crossed and re-crossed the Atlantic. |

Crew Abandon Ship 31 July 1940 Jersey City victim of U99 |

| Historian John Keegan wrote: |

On the 30th October 1945 The House of Commons unanimously carried the following resolution: "That the thanks of this House be accorded to the officers and men of the Merchant Navy for the steadfastness with which they maintained our stocks of food and materials; for their services in transporting men and munitions to all battles over all the seas, and for the gallantry with which, through a civilian service, they met and fought the constant attacks of the enemy." (But still the sailors had their pay stopped when sunk - edit: apparently this changed for the better back in 42 or 43?) The Right Honourable Alfred Barnes, Minister of War Transport said : "The Merchant Seaman never faltered. To him we owe our preservation and our very lives." But for those sailors who served their nation before and during the war, and those who lost loved ones, these thanks rang somewhat hollow. Despite such sacrifice the merchant sailor and families were to receive scant reward. Despite large profits, working conditions were far from comfortable. The basic working week was 64 hours, much longer than in other trades. Pay was usually the minimum allowed under British law, conditions often unhygienic, always uncomfortable. Food was of poor quality. The sailors who created the pre war wealth were those who benefited the least. In 1938, only a year before the outbreak of the war which was to kill so many, the death rate amongst merchant sailors was 47% higher than the national average. 8 years before this death rate was 50% more than of those below the age of 55 on land. So much so that in the 30s there were 150 Charities devoted to the well being of merchant sailors. A vivid description of life aboard the Venetia in 1940: "The bulkheads and deck head had once been cream. They badly needed repainting and were patterned by the dried out remains of hundreds of cockroaches and other seafaring insects. A limp cobweb dangled from a corner over my pillow. Brass fittings were pitted and rusting. The small sink was a network of grease-filled cracks held together by veined porcelain. Overall hung the odour of resident filth...........Insect droppings lay everywhere like the residue of a city smog. I ran my fingers along the edge of the bunk board. They came away black. I opened the door covering the pipes under the washbasin. The place swarmed with cockroaches, bugs and slugs, and it stank." |

|

|

This from a sailor who had his own "space". Here is a description of the 33 sailors who shared: "...lived in the fo'c'sle in the most arduous conditions and without chance of any moment of privacy within it......space was set at a premium and encroachments could lead to anger between exhausted, cold, soaked men. In the tropics it became an oven plagued with flies and cockroaches....In gales with portholes closed and ventilators canvassed over it reeked of rubberised clothing, wet wool and body odours." It should be noted that many convoys completed their journey's unscathed and indeed, some merchant sailors went the whole war without witnessing enemy action be it from U boat or surface craft. But the tension and strain were there for all: "the men in the engine-room suffered the tortures of the damned, never knowing when a torpedo might tear through the thin plates of the hull, sending their ship plunging to the bottom before they had a chance to reach the first rung of the ladder to the deck" Add to this the notorious Atlantic weather and the fact of life that there were little life saving equipment on board these ships. Despite this: "No British merchant ship was ever held in port by its crew, even at the height of the Battle of the Atlantic, when to cross that ocean in a slow-moving merchant ship was to walk hand in hand with death for every minute of the day and night." |

|

|

Not all merchant sailors were heroes I must add. Many ships failed to sail due to crew shortages. Martin Middlebrook writes in his book Convoy that, "the new phase opened in August (1942) with a convoy battle so fierce that the crews of 3 merchantmen took to their boats even though their ships had not been torpedoed. Two crews did go back but the third refused, a most unusual attitude by the normally steadfast British merchant seamen. Their ship had to be left and a U Boat finished it off later. An unnecessary loss. The Battle of the Atlantic, according to Churchill, was the Battle for Britain. The Merchant sailors, the very target for German torpedoes, received no paid leave on returning to port. If a man wished to spend some time with his family, he had to sign off ship and go without pay. Incredibly, under British law, when and if a ship went down, the obligations of the ship owner to the crew went down with it!! The lucky sailors who got home received their pay in full. Should a sailor go down with his ship, the relatives would, unless the sailor was a crewman of a more generous shipping line, receive no pay from the day he died. A sailor who spent 10 days in a lifeboat wrote: "...as soon as you got torpedoed on them ships your money was stopped right away. That's the truth. Everybody kicked up a bit 'cos you couldn't walk about with nothing in your pockets, could you, let's be fair - and all the rum shops were open! Only thing they give us was our clothes....we couldn't walk about naked, could we? Well, we felt devastated because you didn't think they'd ever treat you like that. Because they treated you like you were an underrated citizen, although you were doing your bit for your country, know what I mean? It's hard to think what you been through and what you were doing...and they treat you like that. What did we get? Didn't get no life, did we. I even had to fight for me pension, me state pension. " Protests by Seamen and Trade Unions alike were paid no heed until May 1941 when the Essential Work Order came into force. The 4th Engineer on board the Canonesa, Tom Purnell, earned £15 10s per month plus a war risk payment of £5 per month. His last journey began on 26th July and ended with his death on 21st September he was paid £38 19s before deductions. His Account of Wages, signed by the ships Captain, gives the following gruesome details: Date Wages Began: 26th July 1940 and Date Wages Ceased as 21st September 1940. Not a penny more than was necessary was paid. As one writer noted: "These were the men... upon whom Great Britain called for a life-line during the years of war, and these were the men whose contract ended when the torpedo struck. For the owners had protected their profits to the very end ; a seaman's wages ended when his ship went down, no matter where, how, or in what horror." Churchill Broadcast in 1941: "In order to win this war Hitler must either conquer this island by invasion or he must cut the ocean lifeline which joins us to the United States.... Wonderful exertions have been made by our Navy and our Air Force......by the men who build and repair our immense fleet of merchant ships, by the men who load and unload them, and, need I say, by the officers and men of the Merchant Navy, who go out in all weathers and in the teeth of all dangers to fight for love of their native land and for a cause they comprehend and serve. Still, when you think how easy it is to sink ships at sea and how hard it is to build and protect them, when you remember we never have less than 2,000 ships afloat and 300 to 400 in the danger areas, when you think of the great armies we maintain...and the world-wide traffic we have to carry, can you wonder that it is the Battle of the Atlantic which holds the first place in the thoughts of those upon whom rests the responsibility for procuring the victory?" (Its a shame he did not think more on the welfare of these heroic sailors - mk). A great deal of time between the wars was spent on practising engagements between surface vessels. Destroyers were to act as outriders, deploying their torpedoes against the enemy before a Jutland style engagement between big ships. The Navy’s own official historian records that there was not one single practise in the protection of a slow moving convoy from submarine or air attack. Yet this became one of the Navy’s chief tasks within weeks of the outbreak of the war. Many of the ships were ill prepared. The guns on veteran HMS Walker could not traverse higher than 30 degrees, making them useless against air attack. Destroyer HMS Garland was in the Mediterranean on Day 13 of the war. They had an ASDIC contact, which was unsure, to say the least, But the Captain decided he was going to drop depth charges. The ship was travelling at too slow a speed and the resulting explosion wrecked the aft end of the ship. The Garland spent 5 months in dry dock, at a time when every ship was sorely needed. To meet this shortage plans were drawn up at Churchill’s instigation, for a special “anti sub” vessel capable of mass production. The “off the shelf” design was to be that of the whalers built for the Norwegians. Displacing 925 tons and only 205 feet long, the first ships were named after flowers, and yet these Corvettes became the mainstay of the convoy escort force. It would be another year before corvettes became available to the Navy in sufficient numbers so, in the meantime, trawlers and whalers were pressed into service, fitted with ASDIC and depth charges. HMS Bluebell was one of these “off the shelf” corvettes. Her crew reported to her in Liverpool, preparing to sail as escort, along with sloop, HMS Fowey, on convoy SC7. Don Kirston, a 22 year old regular, was amongst them. “Well what are we going to do in that?”. She seemed more like a rowing boat than a fighting ship. The funnel was the biggest part of her. She had a 1914 4 inch gun and he thought that they would not get very far with that. On her first journey, she ran into heavy seas and about 75% of her crew were seasick. Kirton had false teeth, as he had the real items removed in order to enlist. He tells: “I was at action stations on my depth charge thrower with my two helpers and it was very rough, she was rolling like mad. I had developed a cough and suddenly I coughed my teeth right out and onto the deck, to watch them swishing about with all the water. My two assistants were laughing their heads off! There were my teeth, the only thing I’d got to eat with, going backwards and forwards in the scuppers. I was watching them but could not leave my station. I was waiting for orders to either fire the damn thing or stand down. At last the order “Action Eased” and I got my teeth back”. Convoy SC7 - The First Wolfpack Victim http://uboat.net/ops/convoys/battles.htm?convoy=SC-7 |

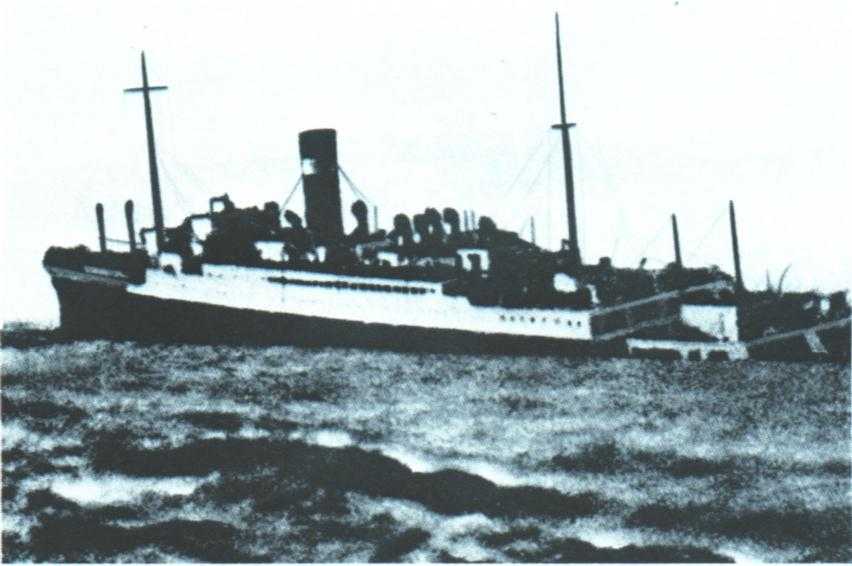

Canonesa |

Jervis Bay. This image was actually taken from the Canonesa (above) in Sept 1940 by Peter Tingey, below. http://www.saintjohn.nbcc.nb.ca/~JervisBay/jervisbaymon2.htm |

Peter Tingey - Canonesa (left) |

|

On the night of September 21st 1940, Convoy HX72, a fast convoy, consisting of 41 merchantmen, was attacked and 11 were sunk. The commodore of the convoy was sure at least 2 U Boats had taken part in the attack. The senior officer of the escorts agreed. There was a suggestion that U Boats were beginning to co-ordinate their attacks. It was altogether unexpected and some influential voices in Naval Intelligence were “sceptical”. (The same “stuck in the mud, old sweats” that thought aircraft unnecessary no doubt) Slow convoy SC7 was to put the matter beyond doubt. The Canadian port of Sydney saw the motley collection of convoy SC7 get underway in the first week of October 1940. SC7 was not expected to make more than 8 knots. Many of its 35 ships would struggle to make half that! The oldest, Norwegian tanker Thoroy, was 47 years at sea. Most of the ships had spent the past 2 weeks at various ports loading cargo, others had already sailed the St Lawrence to arrive here. The SS Fiscus was loaded with 5 ton steel ingots, a floating brick! Frank Holding, a Liverpudlian, recalled how apprehensive the crew were about the forthcoming 2 weeks at sea with this cargo “If you had that sort of cargo you had no chance”. Once a ship like that got hit, it went down like a stone. Holding counted himself lucky to be aboard the SS Beatus, she was a “dirty old tramp steamer – she had the smell of sugar and oil on her. The cooks were Chinese and the engine room crowd Indian. So there was only me and another Liverpool lad”. As Asst Steward, Holdings lot was slightly easier. “ We had privileges over the deck crowd and the engine room. They lived in the Forecastle, maybe 8 to 10 bunks to a room. But I was in a room with just the galley boy”. We were always told that, if we were sunk by a U Boat, they would leave the rest of us, only taking the Captain or the Engineer. We feared machine gunning. 2 friends, Eddie and Billy Howard looked him up at Three Rivers; they were on the Creekirk, loaded with iron ore. By 5 October SC7 was assembled and ready for sea. At the pre sailing briefing some Royal Naval Officers complained about some of the “bloody minded skippers” those that considered that they were better off on their own. For the first eleven days, only 1 sloop was their escort. Only as it approached home waters could it expect any more protection. Some of the ships had been fitted with a 4 inch gun on the stern, but the sailors considered it of little use. A little after midday, the first ships weighed anchor and set off; it would take most of the rest of the day to get the ships “on station”. Nine columns with three or four ships in each column. For merchantmen used to an empty horizon, it was taxing to try to keep station. 4 days out SC7 ran into bad weather and immediately some ships began to fall back. One of the largest ships, the 6000 ton Empire Miniver, was one of these, with turbine trouble. Captain Robert Smith remarked to the Admiralty that “we were peering into the darkness when, to our amazement, we saw a bright light on our port bow. When we drew up we found it was a Greek steamer, it had been visible to us for 6 miles!” So much for the warnings given at the conference. In the early hours of 16th October, one of the stragglers emitted a distress call, submarine attack! The convoys lone escort, HMS Scarborough, could do nothing. Cargo and crew were lost. Spirits were raised when, on the horizon, two escorts were spotted. HMS Fowey and HMS Bluebell had arrived from Liverpool. There was no plan for coordinated action in the event of attack. Late that night, the watch on the bridge of U-48 spotted the moonlit silhouette of a ship. As the U Boat closed it became clear it was a convoy, a large one, and weak. Lorient received a transmission giving reference and speed. A group of 5 U Boats were ordered, find, close, attack. U-48 went in first, instead of waiting for the others and soon spotted the largest ship, the 9500 ton tanker Languedoc, the first torpedo going through the side sending up a column of fire and water into the sky. 2 minutes later a second hit the freighter Scoresby. The Bluebell joined the others in a fruitless search by asdic, but U-48 had slipped away. The tanker was still afloat, settling by an even keel. Some of Bluebell's crew went aboard and retrieved the codebooks. Kirton remembers" Well, what an absolute waste it was, Surely she can be towed, or something like that. But who was going to tow her? It was just war, full stop." Bluebell sank her with a depth charge, they only one she was able to make. A good deal of the 17th was spent rounding up ships. The convoy was spread over 18 miles, some ships did not even know there had been an attack. The convoy was to enjoy a brief respite. U48 followed SC7, but was forced to dive by a Sunderland flying boat effecting loss of contact. But closing in were U38 and U46 (Endrass), U100 (Schepke) and Kretchmer's U99. Frank Holding (Beatus) "That night I went to look over the side, there was a big white patch going from the side of the ship right out to the horizon. Moon on water, and your thinking "someone's out there". You took your lifejacket around with you all the time, on deck or wherever you were going". Frank heard the explosion that took out the Swedish ship Convalleria, sunk by U46: "I went out on deck, there was a young fella there, he was about 16 and he says to me, "I reported a torpedo across the bow to the bridge, I saw it going across". I went back in my cabin and I said to my mates, We'd better keep ourselves handy here". The next thing I heard was this explosion and a sound like breaking glass coming from the engine room. The ship stood still. When I went to the boat deck one of the lifeboats was already in the water, full of water. Some of the Indians had let it go, it was no use to us. That left us with one lifeboat. We knew we were sinking. While we were standing on the deck by the funnel, all this wet ash came down over us, the sea was in the engine room. One of the firemen would not come up, an Indian, we had to go down and get him, forcing him up. We pulled away and I had a mouth organ and started playing. The Second Engineer shouted "Knock that off will you, there's a U Boat on the surface!". I was short sighted, I could hear the engines racing and shouts in German; they sounded excited. A nearby ship, the Boekolo, stopped to pick them up, and it proved costly as she too was hit by a torpedo, water rushing in through No 4 hold and she began to list. The free for all had begun, the next to go was the Creekirk, she sank like a stone, pulled down by her iron ore. All crew, including my mates, were lost." U99 got her. The Captain of the Empire Miniver thought it best to get the hell out of there, loaded down with 10,000 tons of iron ore and steel. There was a dull thump, a big flash, all the lights went out, the engines stopped, the ship shuddered and lay still. It blew all the hatches off and pig iron flew through the air like shrapnel. Once in the boats, 25 minutes later a terrific explosion broke her back and she sank immediately. The Commodores ship, Assyrian, was also hit - by a parting shot from the U Boat he was chasing. They had been in the water about an hour when HMS Leith came alongside. One man left the spar he was holding onto and swam 300 yards to the Leith, he was rescued, collapsed on the deck, and died. In the lifeboat of the Beatus, Frank listened to the noise of explosions all night. He wondered if there would be anything left of Sc7 come daybreak. The fact that his lifeboat was afloat was something but there were supposed to be a certain amount of alcohol, a compass, sea anchor, all these things but, as this was a tramp, nobody bothered. At daybreak, Frank began to wonder about rescue, the sea was also getting rough. Then we heard a voice "I can't stop, there's a U Boat about. I've got nets over the side, when I come alongside you'll have to jump for it and scramble aboard". That's what we did. It turned out to be the Bluebell. The survivors on Bluebells decks numbered more than 200, 4 times her company. Their ordeal ended when, on the evening of the 20th, Bluebell tied up in Greenock in the Clyde. "They took us to some hall and started a roll call of ships sunk. I asked about the Creekirk, "No they all went down with the ship" - my two mates were dead. They put me on a train and I arrived at Exchange Station around 11pm. There was an air raid on and when I got home all my parent's windows were out. Someone told me my mother was under the church in a shelter. I found her and broke down". After releasing her human cargo, Bluebell sailed on to Liverpool. Sub Lieutenant Keachie remembers, "I learned that the Admiralty gave a bounty of 5 shillings per survivor saved so I wrote and requested payment for 200 survivors. They sent us a cheque which we put into the wardroom fund. We never had to buy a drink in the wardroom after that. It was such a windfall. (I presume the ordinary sailors got nothing - mk?). Even before Bluebell had landed her survivors, the pack had found another target, this time HX 79: Gunther Prien in U-47 had found this convoy and he had left Lorient too late to join in the attack on SC7. He had a full load of torpedoes. It was the same story, no attempt was made to coordinate the defence of the convoy, no escort strength in depth and nobody expected U Boats to attack on the surface in strength. At no time did the escorts detect a U Boat on the surface. 12 ships in HX 79 were lost. Survivors were warned not to speak of their ordeals, a veil of secrecy was drawn over all news in the Atlantic. October saw some 63 ships go down. With them went thousands of tons of food, timber, steel and ore, essential supplies. Even in port the merchant sailors were not safe - this time from air raids. A raid on Liverpool on the night of 28 - 29 November 1940 was followed by three in the week before Xmas and more in the New Year. From the deck of HMS Walker John Adams watched the German bombers roll in over the city - "A shower of frozen mutton came down as the ship ahead of us in Gladstone Dock was hit with a bomb and blew up all this meat from New Zealand and up into the air. Some ratings even tried to take some home. I remember the warehouse outside the docks being on fire. The bacon fat was running along the gutter, and several women were running out of their houses with pots trying to save the fat". And still, every week, week after week, crate after crate was unloaded at Liverpool marked "From the USA". Between September 1st 1940 and ! March 1941, the Royal Navy had succeeded in only sinking 3 U Boats. Daily Express November 9 1939 reported that the City Of Flint, an American ship, was at harbour in Bergen, Norway. The newspaper reports that she had been ordered to set sail immediately for America with empty holds. I know German spies were active everywhere, but why give them information in our newspapers? On the same page it was reported that the French Government had ordered £187,000 worth of machine guns from America! Spies in our midst! |

The extremely hostile conditions of the North Atlantic, and below a Liberty ship battles through |

|

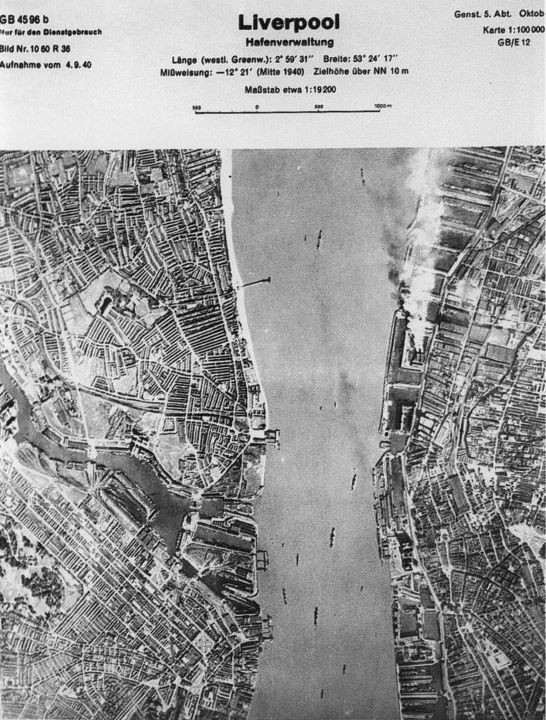

German recce photo of the River Mersey. Smoke from the old power station belching out |

| In February 2007 I received an email: |

| My father was Quartermaster Paul Francis Farrell (always called 'Frank' ) on board SS Designer, which was torpedoed on the night of July 8/9, 1941. She was a T.J. Harrison ship, loaded with munitions. Her sister ship, SS Auditor, was torpedoed four days earlier, but was loaded with less explosive cargo. Obviously, the enemy had information and mistook one ship for the other. Just over eight years ago, I was back in Liverpool to bury my mother and saw the memorial at the Pier Head. A few years earlier, I visited the memorial at Tower Hill in London. I also have some photostats of the pertinent pages of a book in the Liverpool Cathedral. With all of this, I have never felt that the Merchant Navy were given the accolades that were their due. I also had the experience of visiting the command centre in Derby House and was amazed. I had been in and out of that building so many times during the war years and just afterwards, without ever knowing of the existence of those subterranean offices. I'm going back now to really investigate all the information on your site, so you might well hear from me again. Meantime, thank you. It's great to find someone speaking out for the men who wore no uniform; whose only insignia was a little button that said 'MN'.; (My Dad always said it meant 'Maternity Nurse'). and who were the butt of many disgusting remarks on their few shore leaves, because they weren't obviously disabled and weren't in a uniform. My Dad was home in May 1941, during the May Blitz on Liverpool. He worked like a trojan helping the ARP personnel and was especially effective on the night the gas mask factory on Long Lane took a direct hit. He was tireless in dragging out survivors and helping recover the bodies of those who didn't make it. He told us next morning that he would be glad to get back to sea for a rest. Two months later, at the age of 35 years and four months, he had eternal rest. Mary (Farrell) Owens. |

Painted by a secretary of the Bibby Line, a ship on the Mersey in WW2, can't recall the name but began with M (Markland?) |

| September 2011: From Robert Dares.You have a painting of a Mersey ship on your site (above) and mentioned you are not sure of the name but b believe it begins with an "M" If that is the case, I think that is the merchant ship "Markland" from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, that was owned by the Mersey Pulp and Paper Company. My dad was 4th engineer on the Markland sometime in 1943 (I think) During that time the ship was sailing as part of convoys to Trinidad hauling bauxite back for use making aluminum I believe. |

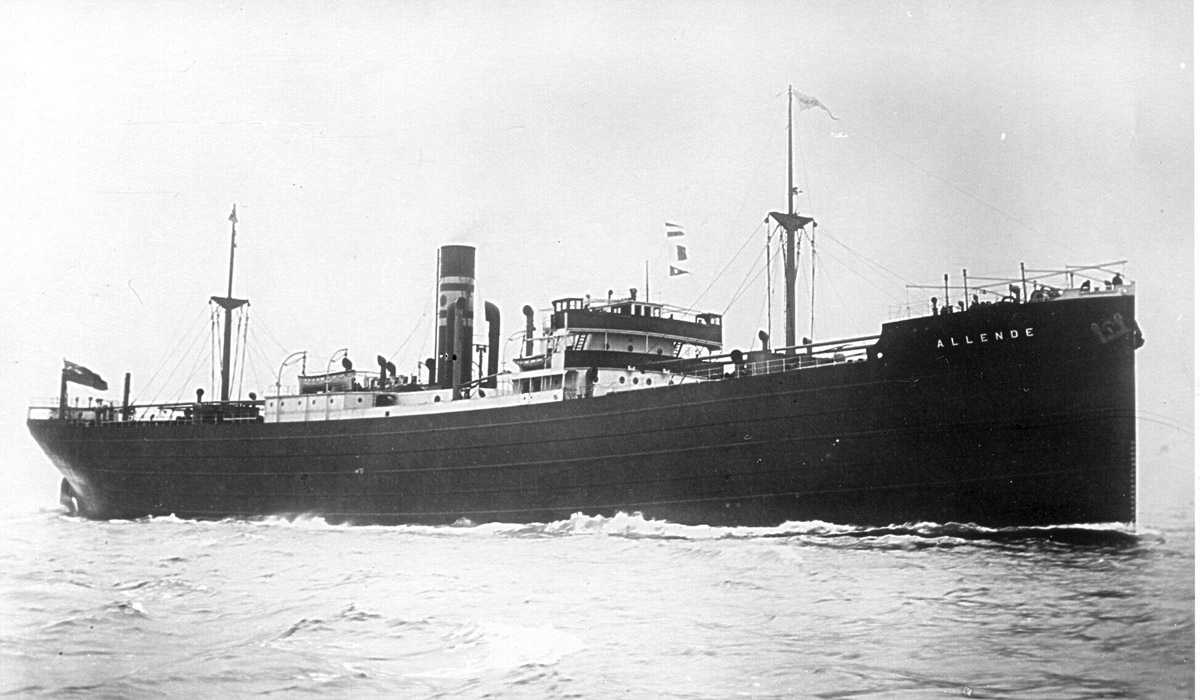

The Story of the SS Allende and her crew (Click Image) |

The story of the Empire Mica (click Image - take you to an external site) |

|

Ed Goodson has the following request for information: |

| Can anyone who served on the Arctic Convoy (JW56-JW67) from Liverpool to Murmansk (July 1944 - May 1945) remember Surgeon Lieutenant Ian Goodson-Wickes, RNVR? He served in RMS EXE (frigate), HMS BIDEFORD (sloop) and Corvettes. In the absence of Adequate war office records I wish to establish his entitlement to the Arctic Emblem. Any anecdotal information would be very much appreciated. If you wish to contact Ed please do so directly on: wickes1 - at - hotmail.com. Replace the -at- with @ to email him. Aug 2008. |

|

| National Memorial Arboretum 25th June 2016 |

|

http://www.worldwartwo.uk/ancestortraces.html http://uboat.net/allies/merchants/crews/ Crews of Ships sunk by U Boat |

|

The Falmouth Branch of The Merchant Naval Association were granted the Freedom of the city on 27th March 2005. Congratulations to all concerned from John Bernard.