Created: 30 June 2004 updated: 16 Jan 2018

HMS Mermaid - Life on Board

By John Murray

(c) John Murray/Mike Kemble 2004

|

Forget the glories of Hollywood or Elstree; here is how it really was, written by a man who was THERE! This is John Murray's story. Pre Mermaid Gunnery Training. Every day during the ten-day course, from the moment we stepped off the bus on Excellent’s parade square, we ran a steady jog in close formation and perfect step from one class of instruction to the next. At the end of our time there, we were praying for old CPO Bridges to come and rescue us and tend to our blistered feet. Every GI (gunnery instructor) relished his part in showing us” what the Royal Navy was really like”. One was reminded of Winston Churchill’s remark about the Navy having at one time been a life of “rum, sodomy and the lash”. We were insulted about our size, our forbears, our inattention, our sloppy dress, and worst of all, our ignorance and lack of agility in working the pieces of ordnance we were being taught how to load, fire and clean. None of us could move fast enough to gratify them. If we dropped one of the heavy dummy rounds on our feet, we were sent on a brisk trot round the parade ground. If we were too slow to ram the shell into the breech, we were sent on a brisk trot round the parade ground. In competition with another gun’s crew, the losers would be sent at the end of the course we were praying for a quick death. Only the discipline we had absorbed at Collingwood prevented us from assaulting our tormentors; but we did get a good knowledge of gunnery.

Commissioning. In early May 44, the draft chit finally came, ending our stay in Portsmouth. About a hundred ratings (i.e. ordinary and able seamen, leading hands, chief and petty officers) marched off to the station for the train to London where we joined the rest of the new ship’s company for the fifteen-hour train journey to Glasgow and Dumbarton on the river Clyde, where HMS Mermaid awaited a crew in Denny’s shipyard. (Our departure from London had been delayed for some hours — one of our number had become drunk and committed suicide. How he managed to obtain enough alcohol and how he killed himself was never explained to us, but it was a considerable shock to those of us who had known him since the training days in Collingwood.) Mermaid was a brand-new sloop of the modified Black Swan class, a type of vessel that was slower than a destroyer but similarly armed. Three hundred feet long and capable only of a top speed of 21 knots, all the speed necessary for escorting convoys and hunting U-boats, she lacked the panache and agility of a destroyer. Her main armament consisted of three mountings of twin 4” high-angle guns, a secondary armament of single and twin Oerlikon heavy machine guns and anti-submarine depth charge equipment. The skipper, Lt-Cmdr John Mosse and his second-in-command, First Lieutenant St. John-Benn and the other officers waited on the jetty while the new ship’s company lined up, collected kitbag and hammock and went aboard the ship to the messdecks, where we found our lockers and stowed our kit and hammocks. The next day we sailed down the Clyde to Greenock where we made fast to a mooring buoy in the stream and ammunitioned ship, a long, hard job, removing heavy 4” calibre shells, which looked like a large-scale version of rifle ammunition, the shell being attached to a brass casing of propellant explosive, 150 lb depth charges and thousands of rounds of Oerlikon heavy machine gun rounds from the barge alongside the ship and sending them below in the magazines. Then followed ten days of sea trials; testing engines, firing guns, calibrating radar and asdic gear (anti-submarine) and generally getting used to running the ship. Testing the main armament took a couple of hours and worried many of the “Hostilities Only” ratings, not so much because we would be involved but because most, if not all, (unless they had been in London or any other large city during the Blitz and heard bombs exploding), had never experienced the routine and particularly the noise of guns of this size being fired. Each gun’s crew of twelve was presided over by an officer, in our case, a warrant officer (a man who had served all his life in the navy and who had come up through the ranks, leaping the gap between messdeck and wardroom). Warrant Officer Smith was well-liked and respected as someone who was always calm and collected whatever happened. The first test required that the mounting be trained to fire each barrel independently. A round was placed in the fuse-setting machine and shoved into the breech. The breech-block clicked shut behind it and with cotton wool firmly wedged into our ears, we stood waiting for the order to fire. The communications rating reported to the bridge and the bridge gave the command. The gun went off with the sound of a heavy iron door being slammed. The blast and the flash made us duck our heads and blink. The ship quivered and heeled a little in response to the recoil. We “loading numbers”, three to each gun, bemused and staggering a little from the sudden shock, hurried to bring more of the 40-lb shells from the “ready-use” locker close by. For test number two, the gun was trained as far as the limit stops would permit, a simple but necessary device to prevent important parts of the ship from being destroyed by her own weapons. All the ammunition for these exercises had been put into only one of the four strategically placed lockers round the mounting. Normally all four lockers would be filled with several rounds, so that a supply of shells would he easily available whichever way the mounting was trained. This meant that when the mounting was rotated round on to one of its limit stops, the locker was certainly not in a convenient or even safe location from which to remove shells. Two of us, Alfie Brown and I, soon found this out the hard and uncomfortable way. We had hurried round the front of the mounting to the locker just as we heard the order to load being given. We heard the breech click shut as we arrived at the locker. The heavy clips that held the door shut were stiff. Cringing and blinking in anticipation of the order “Fire!”, we pulled and kicked at the handles. I glanced fearfully at the barrel - I swear I could see several inches down inside it, Alfie pulled a shell out of the locker. The gun fired. The hot blast enveloped us with an accompanying hammer-blow. The cotton wool flew out of our ears. I fell onto Alfie, who dropped the shell. Deafened and shaking, we seized a shell each and staggered back to the proper end of the mounting, where we tripped on the empty shell cases that were rolling about the deck, causing W/O Smith to remark, not unkindly, “Ah, you’re back! How much do you charge for each performance?” Alfie and I were the butt of a few jokes in the messdeck for a couple of days after that.

Tobermory The sea trials over, we sailed for Tobermory and two weeks of “work-up” period. Tobermory, on the Isle of Mull in Western Scotland, was a fishing village, which had been built by a philanthropic laird, one of the very few landowners of the eighteenth century who cared for his tenants. In a sheltered bay, large enough to accommodate half-a-dozen escort vessels, Commodore Gilbert “Monkey” Stephenson, held undisputed sway. To quote from Richard Baker’s book The Tenor of Tobermory, “over a thousand inexperienced landlubbers passed through his hands, and in the incredibly short time of two weeks, they were welded into a disciplined ship’s company, good enough to take an immediate part in the war at sea. Some 130 U-boats were sunk by Tobermory-trained ships, which also accounted for 40 enemy aircraft.” We had already heard much about the methods used to train “inexperienced landlubbers”, so it was with some anxiety that we entered the little harbour and secured to a mooring buoy. No more than five minutes elapsed before Stephenson’s barge, glittering with polished brass work and gleaming teak, was alongside the quarterdeck in a flurry of foam before even the accommodation ladder had been put over the side. An elderly naval figure swung himself onto Mermaid’s quarterdeck where the First Lieutenant was waiting. Ignoring him, Stephenson looked around briefly, snatched his oak leaf encrusted cap off his head and throwing it onto the deck at his feet, shouted to a passing seaman, “That’s a live grenade! What are you going to do about it?” Unhesitatingly, the seaman kicked it into the sea, where it was fished out with a boathook by one of the barge’s crew, long accustomed to such moves. “Good man”, said Monkey, “I hope your officers are as alert.” Leaving the quarterdeck, Stephenson climbed the ladder on his way forward to inspect the rest of the ship. He reached the bows as the cable party was just completing the business of securing the ship to the buoy. “So what’s your name?” he asked another young chap. “Miller, sir.” “Ah, Dusty Miller, I suppose.” “No, sir, George, sir.” Stephenson looked at him severely. “My boy, in the Royal Navy, all Millers are Dusty. Go down aft and tell the First Lieutenant there’s a fire in the engine room.” In similar fashion our fortnight’s training continued. To quote again from Baker’s book: “The Commodore would come on board and inform the captain that his ship was sinking - and on fire; that he was to engage enemy aircraft with his four-inch guns, and prepare to fire depth-charges at the same moment — despite the fact that his electrical power supply had been shot away and all his officers were dead. “Improvise, my boy, improvise”, the Commodore would shout cheerfully, while lighting a Thunderflash (a very large "banger") from his pocket and dropping it down behind anyone who was not moving quickly enough.” Another story that went the rounds concerned a young and very new sub-lieutenant, just out of officers’ training camp, who was commended for his response when Stephenson came into the wardroom one day and said to him: “There’s a fire on the quarterdeck!” To which the officer replied:” Do you mean to say, sir, you’ve done nothing about it but come down here and tell me?’ So the two weeks passed, some days being spent at sea on a “shoot” at a distant target towed by a tug; another day practising being towed by another sloop, and once on exercises to perfect U-boat hunting with a Royal Navy submarine playing the part of the quarry. With these and other activities the ship’s company began to work and react like a single unit, especially learning how to think independently when officers and other leaders were deemed “dead” or otherwise incapacitated. Towards the end of our stay, we were ordered south to Devonport naval dockyard in the English Channel with a load of anti-submarine gear. D-Day had begun the long-awaited invasion of France, and we were told to expect some action. As it turned out, we caused some “action” of a different kind. The ship delivered the gear, but on leaving the jetty, ran aground on a falling tide, thus guaranteeing a stay of several hours on the mud in full view of the dockyard and, no doubt, being observed by the Admiral-in-command. Like a disabled duck, Mermaid lay immobile for hours, waiting for the tide to change and become deep enough to enable us to float off. During that time, Alfie Brown happened to be looking out of a porthole and saw our navigating officer splashing across the mud with his camera. In his loudest Cockney voice, Alfie shouted, “All my own work, by the naviga’or! !“ who, with good grace, smiled and waved his acknowledgement. We finally broke free from the bottom of the harbour and crept out of Devonport with our tail between our legs, and headed back to Tobermory. No doubt the skipper and navigator came in for some hearty ribbing from Commodore Stephenson when we tied up. Only a day or two later we sailed north to Loch Ewe, where a convoy was preparing to sail to north Russia.

The biggest ship in the convoy was the large and (we hoped) menacing,

but (we feared) tempting presence of a “Royal Sovereign” class

battleship renamed “Archangel”, (see bottom of

page) which was being lent, palmed off on, or

given to the Soviet Navy. She loomed, a grey and inviting target, close

to the middle of the convoy, her ship’s company no doubt hoping that the

surrounding freighters would stop any torpedoes, which a keen U-boat

commander might try to fire in their direction and win glory for his

boat. Also sailing with us were two examples of Winston Churchill’s

brainwaves; freighters which had been converted to small aircraft

carriers. Although able to fly off only a few fighters, they contributed

in large measure to a feeling of added security against enemy

reconnaissance aircraft. The short flight deck, however, made landing,

especially in bad weather, very risky and most pilots had to land in the

drink and hope to be picked up by an escort willing to stop and thereby

chance a torpedo. A movement among

many of the lower deck ratings to emulate his apparent disdain for the

king’s uniform quickly developed. (Benn further won our acclaim by

demonstrating that he was not only a good seaman, but also someone whom

we could trust) We began to come back from leave with various unusual

items of civilian clothing; coloured sweaters, scarves and trousers were

all represented. Jimmy (the universal nickname for any executive

officer) only blinked when someone emerged from the messdeck one morning

wearing a bowler hat. He was quite calm about it. “I haven’t objected to

what you wear so tar, but I must put my foot down. Go and find your

issue cap, unless you want to go on First Lieutenant’s report.” The

skipper, too, favoured unusual though thoroughly practical dress in the

shape of a blue, quilted combination in the style of Winston Churchill’s

“siren suit”.

The convoy was now about 600 miles inside the Arctic Circle in the

latitude of Bear Island. Such an indirect route gave us some protection

against air attack from German bases in Norway. The day after the false

alarm, Red Watch had the forenoon watch. We had just come up onto “B”

gun deck (in front of the bridge) and were standing about chatting and

having a quiet smoke while surveying the ships on our starboard side. It

was the usual grey scene, a low overcast sky, a slightly darker sea, and

grey ships as far as the horizon. Tankers carrying gasoline, freighters

loaded with ammunition, others with armoured vehicles, guns and trucks

in their holds and aircraft fuselages packed on their upper decks.

Suddenly a muffled detonation made Mermaid quiver. Astern of the convoy,

our sister ship Kite had been torpedoed. (another

belief places Kite & Keppel ahead of the convoy on starboard forward

attack party?) The confusion aboard her must

have been indescribable. Watches were changing, with almost the entire

ship’s company on the move; the watch being relieved would have been

looking forward to breakfast and sleep and the new watch would have been

thinking about the next monotonous four hours. Kite sank in one minute.

Only nine of her ship’s company survived. It was some consolation to

learn that the attacking

U-boat (U344) was soon after sunk by aircraft action, likely

a Sunderland coastal command flying boat from a base in Scotland.

(Actually it was a

Fairey Swordfish

from HMS Vindex, an accompanying Escort Carrier - mk) (At the official

enquiry into the loss of Kite, it was revealed that the captain, who was

actually a submariner with little or no experience of commanding a

surface vessel, had ordered that the ship reduce speed to a crawl to

allow the (it had tangled - mk) anti-acoustic torpedo gear being trailed astern to be reeled

aboard, and that the course be maintained in a straight line rather than

the customary anti-submarine zig-zag, both of which conditions made Kite

an easy target. The transcript of the enquiry report can be found on

the HMS Kite webpages.)

Patrols & Boiler Cleans

We were ordered to Liverpool on the west coast of England, a large city

with an extensive dockland. Gladstone Dock had become the headquarters

of Admiral Max Horton who commanded the

Western Approaches, a vast area of the

Atlantic Ocean stretching from Iceland to northern Spain, and extending

two or three hundred miles westward. The Dock was home to a large number

of escort vessels -- sloops, frigates, corvettes, Hunt class destroyers

and some of the old American four-funnel destroyers, relics of the Great

War, as well as some new American - built flush-deck destroyer escorts,

both types notorious for behaving in a frightening manner in anything of

a seaway. Lastly a few V and W British destroyers, also built during the

first World War, now fallen on hard times by having a boiler removed (as

well as a funnel) to reduce their speed from the original thirty knots

to a mere twenty, the only practical speed for convoy escort work.

We shared the job with the Canadian destroyer Saskatchewan who took up station a mile or two on the port side of Otranto. As we steamed north, the weather became worse — the wind stronger, the seas higher and the skies darker. It was one of our first encounters with what the North Atlantic can do in winter. At least it kept the U-boats down below periscope depth and enemy aircraft grounded. The world took on the now familiar various shades of grey. The horizon was blotted out by spray and low cloud. We were heading at a forty-five degree angle into the oncoming seas, many as high as thirty feet, their crests breaking and roaring towards the port bow, making the ship pitch (from bow to stem) and roll (from side to side) at the same time. Steerageway was maintained at about five knots to reduce the force of collision between the approaching seas and the ship’s forward motion, drawing the usual insults and encouragement from the ship’s company. “Go on, roll you bastard; you’ll get tired of it before I do.” “Smash that bloody milestone, there’s more coming along.” “Who the hell’s steering — that’s my second cuppa spilled!” Mermaid corkscrewed awkwardly and heavily towards Iceland, her bows

rising quickly, hesitating, and just as quickly dropping into the next

approaching wall of water. Standing in the shelter of ”B” gun, you could

see down into the blackness of the trough between two foaming crests as

the ship plunged downwards into the “milestone”, striking it with a jolt

and a shudder and throwing solid water back over the fo'c'sle around

“A” gun mounting, crashing into “B” gun deck and hurling what remained

over the bridge. The impact brought the ship to a ponderous, shuddering

standstill, heeling to starboard as the waves bore her up and passed

under her, leaving her lurching to port, bows already falling into the

next trough. Water found its way almost everywhere below decks. The port

passageway was flooded almost to the six-inch high coamings (sills) of

the doors — a shallow river, slopping madly from one end to the other.

“A” gun mounting had sprung a leak, spraying water into the messdeck

below. Lifelines were rigged along the quarterdeck towards the stern,

that part of the upper deck closest to the sea, more to provide

psychological comfort than to be of much practical use. The “gash”

(garbage) had to be ditched through the chute at the stern, gale or no

gale. Hanging on to the lanyard on the lifeline with one hand and trying

not to spill a sloppy bucket of gash was not a popular job. There were

plenty of stories about people losing their footing, being washed

overboard between the guardrail wires and being washed back aboard by

the suction created by the rolling of the ship. It was during this trip that I was “promoted” to join the bridge lookout

fraternity. We sat, two on each side of the bridge, on a swivel seat to

which was attached a pair of binoculars and a small circular bearing

table marked in degrees. Two lookouts swept the horizon ahead and two

astern. It was drier, we were able to sit, but there was no opportunity

to walk about and keep our feet warm. If the wind came from astern, we

were frequently enveloped in sulphurous fumes from the funnel, not more

than fifteen feet behind the bridge. (The worst place to catch the fumes

was in the lookout position up the mast, only about eight feet above and

forward of the funnel. In a following wind it became too dangerous to

allow a man up there. Whenever the ship altered course the

officer-of-the-watch had to be reminded that someone was choking in the

“crow’s nest” waiting to be ordered down.

Back to Liverpool

The Mediterranean

The following information is taken from http://www.naval-history.net/xGM-Chrono-18SL-HMS_Mermaid.htm

1 9 4 4

May

Carried out contractors trials and commissioned for service. 12th Build completion and commenced Acceptance Trials.

Retained in build yard for repair of defects found on trials.

On completion of trials and storing took passage to Tobermory.

June 2nd Commenced work-up for operational service at Tobermory.

July Under work-up which had been extended. 17th Completed work-up and taken in hand for further repair before operational service,

August

Under repair. 13th Deployed with Home Fleet for convoy defence.

15th Joined HM Sloops KITE and

PEACOCK, HM Destroyers

WHITEHALL in escort

for Russian

Convoy JW59 to reinforce defence against

aircraft and submarine

attacks. (Note: This convoy included battleship ARCHANGELSK (Ex HMS ROYAL SOVEREIGN and ten Ex USN PT boats being transferred to Russian Navy).

For details of all Russian convoy operations see CONVOYS TO RUSSIA by RA

Ruegg,

CONVOY! by P Kemp, THE RUSSIAN CONVOYS by B Schoefield and ARCTIC

CONVOYS !

by R Woodman. 20th JW59A under U-Boat attack by T5 acoustic torpedoes 24th After detection by SWORDF1SH aircraft of 825 Squadron from HM Escort Aircraft Carrier

VINDEX participated in sinking of U354 in position 72.49N 30.41e with

HMS KEPPEL, HMS

PEACOCK and HM Frigate LOCH DUNVEGAN. There were no survivors from the submarine. (See U-BOATS DESTROYED by P Kemp.) Detached from convoy on arrival at Kola Inlet.

28th Joined escort for

returning convoy RA59A with same ships.

September

2nd Took part on sinking

of U394 in position 69.47N 04.41E, west of Lofotens, with HMS KEPPEL,

HMS WHITEHALL and HMS PEACOCK after detection by SWORDFISH aircraft from

HMS VINDEX (825 Squadron).

6th Detached on

arrival at Loch Ewe with comparatively little interference.

12th Taken in hand for repair

of defects.

October On completion of repair deployed on convoy defence in NW Approaches.

November Taken in hand for refit at commercial shipyard in Leith. 1945

December

Under refit

1 9 4 5

January Nominated for service with 12th Escort Group for defence of Atlantic convoys.

February

On completion of shipyard work carried out post refit trials

Passage to Tobermory

March 23rd Completed work-up at Tobermory.

Joined Group based at Liverpool.

April Deployed for defence of coastal convoys and in SW Approaches

May After VJ Day nominated for service with British Pacific Fleet. on completion of refit 14th Taken in for refit at Portsmouth to prepare for foreign service.

June Under refit. (Note: Work done included alterations to suit tropical service.)

July 17th On completion took passage to Malta for work-up.

24th Commenced work-up with

ships of Mediterranean Fleet.

August Work-up in continuation.

|

|

12 Oct 04. Andrew Hutchings would like to contact any member |

|

The excellent U-Boat site http://www.uboat.net shows this entry for this particular trip of the Mermaid From John Lowrie: My father, George Lowrie served on the ship from May 1944 to March 1946. He was a Stoker 1st Class. |

24 Aug, 1944

2 Sep, 1944 |

|

German View of ASDIC Chief Engineers Report of Patrol 2 of the U-330** See note below I believe the Kommandant

has discussed the new ASDIC sound to you. I feel that the Allies have

developed a new style of ASDIC which can now pinpoint our depth, as well

as direction and range. Additionally, their wasserbomben are now able to

sink to 150 meters before detonating. This is a big step, since we were

always able to dive deep and remain well below them. This, along with

the new ASDIC sound presents a whole new problem for us. Please check

into a type of ASDIC called the “147”. I have heard a bit about this at

the “Scheherazade” in Paris and until now was no more than mere

speculation. Also, I am aware that our Chief Mechanic, O. Masch. Harry Jaschinski, seems to have little regard for the proper operating temperature of the diesel engines. I have seen the temps on the exhaust manifolds reaching very high critical parameters on the last two patrols and have spoken to him several times regarding this; evidently to no avail. This has also been brought to the attention of our Kommandant Oblt. S.M. Grabowski, who has had several talks with Jaschinski, but with little effect on his operating practices. He suggested we look at his operating practices on the next patrol, after a pre-patrol talk and take greater action, should the need arise. I am convinced to try this. All other systems seemed to function well. No cooling problems on the diesels, despite running flank several times for hours on end. Chief Engineer’s Report

Respectfully Submitted on this date: 28 NOV, 1939 http://home.t-online.de/home/sgaertner/9gpc2.htm#top **Obviously in error because, as Peter Hulme pointed out to me, U330 was never completed and scrapped. Probably just a typing error. Also the date of the report is incorrect as Brest was not a U Boat base in 1939. It is possible that the whole report is a fake, but ...... ??? |

A letter from Bernard Miles, famous actor regarding HMS Mermaid. Thanks to Allison Furnell for the above letter

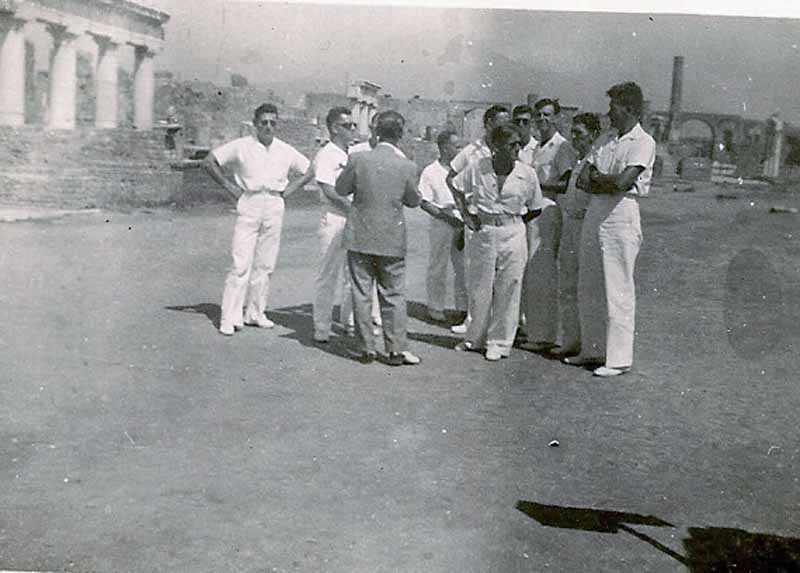

Bev Moir sent me an email 13th January 2008 enclosing two images of her

father, whilst serving aboard Mermaid, in the immediate years following the war.

They give the appearance of Greece but I believe this is Carthage? Especially as

Patton visited here and was well documented.

Bev's father is second from the left in the image below and far right in the image above.

|

Memoirs of Life on board HMS Mermaid by Jack Powrie – Petty Officer 1945 - 1947 In 1945 after the war in Europe had ended, HMS Mermaid left Great Britain again, this time for the Far East as the war with Japan was still raging. But two atomic bombs dropped on Japan by American aircraft brought the conflict to a quick end and so the Mermaid returned to the Med for the next four years. She began by cruising North Africa, stopping in at such ports as Alexandria, Port Said, on to the island of Crete, then on to Cyprus before going back to Sliema Creek just down the coast of Malta from the Grand Harbour, Valetta, Sliema Creek being the place where Captain Johnnie Walker’s sloops all docked, anchored to buoys all in a line inside the creek. Captain Walker, later to be promoted to Rear Admiral (and as any man who served with and under the command of the Captain will testify, his promotion was well deserved). As Flotilla Captain of all the Royal Navy sloops, the men of the sloops revered Captain Walker as being another Horatio Nelson. He was a man of discipline and fairness. He was a man of brilliant tactics and cunning. He was all that a senior officer of HM Royal Navy should be. The day I joined HMS Mermaid in Malta happened to be the Admiral’s inspection of Mermaid and HMS Pelican (sloop). Also the day before, we sailed for a Med cruise to “show the flag”, calling in just about all Mediterranean ports. A great honour for the Mermaid and her crew before her next duties – the Palestine patrol. First stop of the tour was at Nice, French Riviera. We anchored in the bay and were met by lots of small boats just crammed with people, all wanting to come aboard after we dropped anchor. We stayed at Nice for two days then carried on to Cannes further along the Riviera coast. Stayed there for a few days then on to Beaulieu for the festival of the mimosa flowers. We dropped anchor approximately two to three hundred yards from shore and even at that the perfume of the mimosa flowers drifted out in the Bay. The second day there we had open ship for the town’s people. They came out by the boat load. “Hide your gear and lash down all the ship’s fittings” or they would be gone for souvenirs. A lot of visitors brought bottles of French wine with them to give to the officers and crew – much appreciated of course. We had parties thrown for us all French stops by the locals. It was a great start indeed. During our call at Cannes, the folks put on a bus tour for us along the Riviera and inland to the mountains as far as Grasse. This is the home of Chanel No 5 perfume and of the first perfume factory in France. We were each given a tiny bottle of this perfume to keep. They told us it never loses its distinct smell and will never evaporate. I think most of the crew gave it away at some later time to girls in other ports. As for my bottle, I bartered it away in Italy for a cameo brooch for my mum – sent it to her for Christmas 1946. The next stop was Monte Carlo for four days. We tied up at the front, near the railway station which was at the bottom of the hill from the Casino, very large to very small luxury boats all around us. King Farouk of Egypt’s mini liner was tied up near us. I believe it was an official visit to Prince Ranier. Quite heavily guarded by his own Egyptian guard, King Farouk’s guards wore splendid uniforms and all spoke English and French. It was certainly spotless whites, number 1’s at all times when on deck or ashore of course. The King came aboard HMS Mermaid for a visit to our captain and an informal look about, even below decks. Think he spoke to just about all of us aboard - quite an informal visit. A constant stream of horse drawn four seater landaus came down to the gangways to take us for rides about Monte Carlo and to see the gardens and the Royal Palace. We were all presented with a few complimentary small tokens from the Casino on our first days in Monte Carlo. A couple of the crew won quite a bit of money when they gambled but just about everyone else just lost their tokens back to the Casino. The day we left, we had a good send off. The Prince was there, his Palace Guards and his band and the Monte Carlo band. I think just about everyone in Monte Carlo and surrounding area were in town that day. It took a long time to clear the small ships to leave an exit for us to get out of the harbour and what a noise! I am still not quite sure in my mind as to whether they were all celebrating the end of the war in Europe again or just glad to see us leave? I’m sure it was the former though. We had one small incident when leaving the harbour. The Mermaid was about to clear the harbour entrance when some 70 – 80 foot luxury cruising vessel type decided that his boat had the right of way over HMS Mermaid and cut clean across the Mermaid’s bow. He was going into the harbour regardless of what. There she was, cutting a wave as high as her bow determined to cut off our exit. Our captain, Lieutenant Commander Kimpton must have been going frantic on the bridge by this time. The stand to crew for leaving harbour had a bird’s eye view of this from their positions on our bow. Apparently they were all wishing the Mermaid would let him amidships, but that was avoided at the last second. Luckily we were doing no more than about 5 knots at that time and Captain Kimpton called for emergency reverse screws. I believe that saved the day and avoided and Admiralty enquiry. Farewell Monte Carlo. We cruised on then to Corsica and docked alongside the main square at Ajacio, the capital and birthplace of Napoleon Bonaparte and of the Musketeers. The first thing you see when docking is this gigantic statue at the other side of the square of the musketeers. It is about the most impressive statue I have ever seen. The statue of Napoleon on the north coast of France, facing England over the channel, impressive as it is, pales in comparison to this one. It looks over the whole square and town of Ajaccio – striking to say the least. This square is where all and sundry congregate to discuss everything that has happened today I think. Of course work spread very quickly throughout Corsica that a warship of the Royal Navy was tied up at the square in Ajaccio. What was a relatively quiet day usually soon turned into people and families arriving by bus and train from the hills to come see this English ship in their capital. I’m sure that every man jack of us aboard Mermaid, had our photo taken a hundred times posing with the locals and visitors. Some of us took the mountain train to have a few hours at the highest village in Corsica. A village called Vizzavonna. Not much up there but a few people, goats, small houses of sorts and rock. Most of Corsica is just rock. We left Ajaccio in 90 degree sunshine and arrived in “Vizz” about 3 hours later. Steadily climbing and stepped out in 3 inches of snow. Crystal clear sky and just about the freezing point. It was worth every minute of the journey believe me – very friendly people. They couldn’t do enough for us either. These were the folks who had to stay up there whilst the others had gone down to Ajaccio to see HMS Mermaid. They were delighted as they thought that because they couldn’t come visit us, we had come to visit them. In a way we had. We were wined and dined until the train left to go back again to Ajaccio. All the houses and buildings had fires burning to keep the chill off and seeing that we had braved the journey up wearing our whites, shorts and all, they certainly looked after us for the day. I went up again the following day with the off duty watch but his time we all wore our Blues. The people were delighted to meet the other half of the crew. I explained to them that No. Another vessel had not arrived in Corsica. They then took care of us all again and again, more poses for the cameras etc. The train chugs through a few villages en route. It also picks up and drops off a few men who go hunting for the day. The train just travels a wee bit slower for them to get on or off, but never stops until it reaches Vizzavonna at the top or Ajaccio at the bottom end. All in all it was a good day out. It would be a surprise to the locals who came to Ajaccio on the 5th day to see the Mermaid, only to find nothing there. We slipped out at 3a.m. and were on our way elsewhere by sun up. An interesting note to this visit – I was told by one of the town dignitaries before we left, that never before had a British warship ever visited Ajaccio in peace time, only during the various wars with France. The Mermaid never returned to Corsica. The next ports of call were in the Greek islands. Everyone aboard had to take quinine tablets before setting foot anywhere in Greece or its islands, a lot of malaria there at that time. We visited the island of Argostali first for one day only. It is a small rugged island with one small town, all fishing and goats. It has one main street along the shore and the people were very suspicious of us. They didn’t say much and hid in their homes when we walked by. Not even the owners of the local pub and hotel cum restaurant were what you might say, friendly. They served your orders of food and drinks but hardly cracked smile or talked. Just charged high prices and amazingly never had any small drachmas or local coins for our 1,000D bills, the smallest bills the R.N. gave us at that time – an experience anyway. The next stop over was the island of Dragonesti. We spent two days there anchored ½ mile off shore. This is a similar type of island as Agastoli, geographically that is. But what difference in the people! Again, a one street town, village? along the shore, fishing mostly but al couple more bars and places for food. The folks had a great time partying the two days we stayed there. Shore leave was noon until 2200 hours both days. The last whaler left the jetty for the Mermaid promptly at 2200 hours and even if the locals brought you back after the whaler had left, you were on charge of course. Never that I remember, did anyone abuse shore leave time. The Mermaid seemed to have a reputation amongst the other sister sloops for being a bit wild. I don’t know why, but her crew never abused their privileges. She was a tight ship and was always run with the highest R.N. strictness, which we all aboard appreciated. Hence, we never took advantage of slacking off. Sailed on to Pireus, docked there for a few days in Athens, before heading north up the Adriatic – destination Trieste, Italy. Not long out we were hit by a surprise Borer sweeping down from the Italian Alps. The Mermaid was blown astern back into the Med, in spite of the chief engineer giving the engines all they could muster. We were still going astern. Five days we were battered and even the crew members who were on Mermaid on Russian convoys had to admit that this blow was the worst ever, especially A.B. – Alfie Brown. Although he was in the next mess to 9 where I was, you could hear him moaning about Russia through all the deck, but even he conceded this Borer was the worst yet. I really think that Alfie just moaned about things to keep everyone awake, mostly an easy type really. When the Borer blew itself out finally, we sailed back to Malta for repairs. The upper deck was in shambles. Even “Chippy” couldn’t repair the whalers or the skipper’s gig. Between decks wasn’t much better, no crockery left, sea water had ruined just about everything. Lots of repairs to be made to say the least. This time we sailed in to dry dock, by this time the Mermaid needed her hull scraped of barnacles and a complete new paint job. After approximately, one week we were out of dry dock and ready for whatever came next. Mermaid sailed up to Venice to meet up with HMS Pelican where she was tied up alongside the Doges Palace by St Marks Square. Mermaid tied up at the main jetty also, just down from Pelican by the Bridge of Sighs. The Mermaid came in under great scrutiny from HMS Pelican and some idiot, “no names, no pack drill” stuck his head outside of a scuttle (port hole), for a look around and was spotted by Pelican. We were told by the O.D. later that our skipper got a royal telling off from the Commander of the Pelican for allowing some ruddy AB to stick his ruddy head out to be chopped of if it happened again whilst either entering or leaving port. Of course the senior captain was right, but the AB at fault knew the rules of the R. N. about entering and leaving harbour. The AB culprit got himself a royal reprimand from his desk Petty Officer and the rest of us below decks, as we were all denied shore leave that first night because of the incident. We gave him a rather hard time that first night as he knew that as the crew of the Mermaid, we had our own code of conduct to obey as well as the Royal Navy’s King’s rules and Admiralty instructions. All the officers and crew of the Mermaid had a good time in Venice for a couple of days before leaving for Trieste, Italy. Upon docking at the main jetty close to the main square in Trieste we had two days of shore leave and then we sailed again – this time for the port of Pola, Feume. Italy still claimed the port after the war was over, but Yugoslavia wanted it back as it belonged to them before the war began in 1939. Now the transfer back to Yugoslavia was to take place and HMS Mermaid was there to make sure that this is what took place peacefully. Mermaid tied up to the inner jetty for the night but no one was allowed ashore as the Italian troops blocked off the jetty from the main causeway. The only people allowed through were the ranking people who were to sign the documents for the transfer. These people came aboard to visit the skipper and the officers. First the Italians, then they left and let the Yugoslavian officers through to visit the Mermaid. The Italians were to the port side of us in the harbour and the Yuglslavs to starboard. Both regiments in full view – flags, bands, troop, rifles, fixed bayonets and side arms. The Yugoslavs in olive green, drab uniforms and the Italians dressed in brown jackets, creamy coloured breeches with high patent leather belts and boots, very fancy caps and hats all with feathers fluttering in the breeze - quite a sight to say the least. The Yugoslavs looked ready for battle and the Italians looking for a big parade. All secure here. The following morning, the day of the transfer of occupation, Lt Cdr Kimpton ordered, “let go for and aft springs” from Mermaid to Jetty and Mermaid left the jetty for good and dropped anchor approximately 50 feet out, broadside on to the town and there she stayed. It was approximately 1400 hours when the shore activities began - both sides shouting orders to their assembled men. Then the bands of both sides started playing at the same time, each out to better the other at making a racket! After about an hour of hectic movement on both sides, they finally quietened and order was restored. The music?? stopped and then finally no more orders shouted. The silence became eerie for a minute or so, then a bugle blared out on the Italian side and the troops turned right, ad to the sound of marching music Italian style, quick marched off the jetty and headed towards the Alps and back to their own country. At this moment the Mermaid’s X Gun swung to port and fired a single gun salute, then swung back to her stern position again. The activity started by the Yugoslavs then took place. Orders were given, rifles with fixed bayonets shouldered, flags hoisted, the band started up and along the jetty they marched, a very impressive looking lot too. They looked like soldiers, but maybe it was just the uniforms they wore? But aboard Mermaid we all agreed that we would rather have them with us than not if ever anything happened. After taking over and coming to a halt, they left turned to face Mermaid. The band went quiet and at that time the ship’s A Gun turret swung left and covered the Port of Pola and fired a single gun salute, swung back to face her position forward and then there was a moment of silence before the Yugoslavs cheered and some even threw up their caps into the air. Then you could hear the cheering from the people of the port as they rushed to hug their troops. It was over. After order was more or less restored ashore, the Yugoslavs had their band play their anthem and all hell broke out again. It all quietened down when Mermaid swung A, B, and X gun turrets towards Pola. All three turrets fired their 3.7’s at the same time with an ear shattering roar and a belch of flames and smoke in a broadside that even Nelson would have approved of. She then brought her turrets back to position and began hoisting anchor. At the same time “Bunts” hoisted the Yugoslav flag. The crew for leaving harbour were smartly assembled fore and aft and we began to leave to the cheers from shore. As we headed out into the Adriatic we could hear fireworks exploding and rockets making a great display even though it was still daylight. Before this handover of power between the countries of Italy and Yugoslavia we had made numerous runs between Trieste and the Sea of Crete, down the Yugoslavian coast, through the Corfu channel, along the Albanian coast, the Greek coast and islands searching for illegal immigrant vessels heading for Palestine. There were also a lot of illegal gun runners about that time also as the Yugoslav uprising with Marshall Tito at the helm was taking place. It kept the Mermaid very busy to say the least. During the evenings and nights when we were off the coast of Yugoslavia, Tito’s supporters would light up great bonfires spelling out “Tito”. You could hear the small arms fire from out at sea coming from the shore and up the mountains. As all this was going on it was a case of daylight watch for mines and keep your fingers crossed after dark. There were quite a few loose mines bobbing about then. This kept the ship’s coxswain on his toes through trying to blow these strays before they placed a hole in our hull. HMS Volage and HMS Sumares, both destroyers, weren’t quite so lucky. During night patrol in the Corful Channel, the Volage hit a mine and sank and the Sumares took one in the bow, which blew her apart like a tin opener. Port and starboard plates were torn open and forward deck was peeled back and up so that the bow decking was actually resting on the bridge – quite a site to see. She was towed stern first back into Malta for repairs. Back to the Mermaid coxswain – the loose mines kept him quite happily trying to explode them with rifle fire. Of course you have to hit the horns to do that, otherwise you just put .303 holes in them and eventually they sink. Except for an expert sniper, “and the Lord only knows poor old Cox was not”, to hit the horns at a few hundred yards, even in a calm sea would be a feat, but with the ship’s movement and the mine bobbing about, the rest of us hardly saw any mines blow up at all – mostly holed and just sank in time. We used to tease him terribly and the more we teased the worse shot he became. Sometimes if things were taking too long to rid the mine from the sea the O.D. Officer of the Day on duty would order the orlecon gun to have a go much to the delight of the gunner. A short burst and it either blew up or sank in a few seconds. Even the turret gunners would ask Cox if he would like to use one of the main armament guns the next time as it would do the trick right away and also it wouldn’t cost the admiralty in London as much as the number of bullets he wasted for nought. We continued our patrol again for illegal vessels and it was our second patrol down the Adriatic that the Mermaid increased speed all of a sudden and kept heading south at increased knots. The word was passed below decks that we were in a hurry to get to a merchantman, holed by a mine in the middle of a minefield south of Salonica, her condition unknown, but there were casualties aboard. That would explain the hurry but was it just a lower deck buzz? As it was almost Christmas 1946 we could only speculate. Mermaid entered the Sea of Crete again then turned north after clearing the Greek islands and Athens. It definitely appeared plausible the buzz may be true after all. We were now in the Aegean Sea. We sailed pretty well flat out “18 – 19 knots that is”, tops for a sloop, all night and into the following day. Just a couple of days before Christmas and there goes our fancy Christmas dinner became the word. All aboard were looking forward to this day as it is the only day each year that the officers served the men and except for the duty watch, all could relax and do whatever. Approximately 1400 hours the following day the Mermaid started to reduce speed, we were closing in on the mine field. We could easily pick out the mountains over looking Salonica and could see a vessel at a stand still a few miles away between Mermaid and the Greek shore. The skipper ordered all available men not on duty to line the upper deck from bow to stern, port and starboard as mine lookouts with all crews left on standby. Soon the ship was at a crawl, then she entered the minefield to reach the stricken vessel. The mines were drifting slowly by a few feet away just under the surface, or so it appeared. Those of us close to the bridge could hear the occasional order being given by our captain. Other than that all was quiet except for the lap and slap of the waves at the bow. Occasionally there was the crack of the rifle held by the coxswain who was taking the odd pot shot at any mine that broke loose in our slow wake. No explosions though. Twice it would seem that we were through the field. We couldn’t see the mines, but then the skipper would give another order and the ship would turn slightly and there they were again. Finally we reached the stricken vessel which was down at the bow and listing to port and Mermaid eased up to her side for boarding. Our First Lieutenant and the sick bay tiffy boarded her first to tend to the injured, followed by the chief engineer and his repair party to see if she could be made sea worthy, or was she to be sent to the bottom where she was? Three of her crewmen were dead and a few others had injuries. The tiffy stayed aboard her and the chief and his crew, along with her own engine room crew tried shoring up and plugging gaps in the hull forrad. Days later she was made sea worthy, the dead blessed and put over the side where they had died, then we hooked onto her and towed her out of the mine field and back for repairs in Malta to be docked for salvage. An eventful Christmas and New Year to say the least: it was all worth it to us a year or so later when we all received letters from the Admiralty in London with a cheque amounting to our rank for the salvage of the vessel. The Mermaid left Grand Harbour and docked again at the buoys in Sliema Creek for a few days ashore before resuming our duties at sea, during which time we re-armed for some practice firing at the smallest island in the Malta chain of four. This rock was used by Captain Walker’s sloops for target practice before leaving Malta to keep his gunners, and indeed, the whole ship’s company sharpened up to R N standards at all times. Between gunnery practice and exercises involving other vessels at night time, it kept us hopping without sleep for sometimes three days before the exercise was over when the ships were rated for efficiency. HMS Mermaid was always up there at or near the top. These exercises were very serious and were as hard on men and ships at the Gun Run at Pompey or Chatham. It was during this last practice before sailing for sailing for Palestine again, that the left 3.7 gun of A turret was brought into question by our skipper. To find out the problem we made another run around the rock. I was observer standing immediately behind the gun crew leader. A Petty Officer gun layer for the port 3.7, a full time PO who was drafted to HMS Mermaid from her first run ups in 1943 and a sixteen year veteran of the R.N. First round fired – the result, off target. Second round fired – again, off target, yet the instruments were right on as confirmed by the P.O. and myself. Adjustments made to the turret instruments etc. – third shot, right on target. To make sure it wasn’t a fluke, we made another run around the island and had another shot for accuracy. Coming around now, target sighted, swing turret to port, aim steady as she goes, fire. Not much happened but a fizzle and a lot of smoke. Then the shell fell out of the muzzle onto the deck and started to roll astern towards B gun deck and the bridge. This was when the gunnery Warrant Officer leapt into action from where he was standing to observe the turret crews timing etc and like a true Royal Navy man, he ran forward, scooped up the shell, ran to the rail and threw it into the sea. After that, we made two more runs around the island, fired a few more shells, all right on and none were duds this time. Back to Sliema Creek where we waited for the Jenny Wrens to bring us more 3’s in their LCMs before departing for Palestine. Mermaid also took on planks of wood, chicken wire by the roll and other items of use for building for a coop?? It turned out that these items kept Chippy and the AB’s quite busy during our next few days at sea, building boarding ramps and protection for the boarding parties when encountering illegal vessels. It seems that after the “Exodus” was chased to Palestine and had grounded herself just south of Haifa, word was that other illegal ships’ passengers were hurling anything loose down onto RN ships trying to apprehend them within the three mile shore limit as laid down at the Geneva Convention. Hence the chicken wire protection. These poor souls aboard the illegal ships were survivors of the Nazi concentration camps who were trying to go to Palestine to build a new state of Israel as promised by Ben Gurion, who also informed them that if apprehended by the British, they would be treated worse than they were in the camps. We also found that the people escorting to this promised land were also Ben Gurion’s people, there to incite trouble if and when the sailors tried to board the ship. The only protection the small boarding parties had was a three foot stick with a tear gas canister at the end to keep people back from injury by flying bottles, nuts and bolts and sometimes bare fists. A lot of RN ratings were badly injured during boarding illegal boats. The boarding and taking of these ships had to be done within a three mile limit of Palestine as laid down in Geneva and so it had to be quick. We had weapons, but again, couldn’t use them at any time. After a successful boarding, the vessel and all people aboard were taken to Cyprus for processing before being allowed to enter Palestine, and in the case of the “Exodus” who managed to step in and grounded. All the crew and passengers were apprehended by the British troops waiting ashore for them if they jumped ship. All were then taken to Famagusta, Cyprus for due process. The Mermaid docked in Haifa harbour a couple of times, tied up to the sea wall jetty where for 24 hours a day the “Captain’s Gig”, it being the fastest thing aboard, was used to zip around the harbour, fairly close to the Mermaid at various odd times and drop grenades as a prevention against frog men trying to attach limpet mines to the hull to go off in a few days when at sea again. This happened to one of our sister ships and the skipper of HMS Mermaid was not going to let this happen to his command. One time in Haifa when ashore, the bank on the main street blew up as we neared it. The seaman I was with all carried rifles and myself a .45 Navy Colt side arm, but we were not allowed to use them until or unless fired upon. Another time a vehicle slowed down and a grenade was tossed out of the window and rolled down the pavement. Everyone about, including civilians ducked into shops and doorways. A lot of people, soldiers and sailors were killed that way. Ben Gurion’s men used to fire down from the monastery at the top of Mount Carmel. It wasn’t very safe to be exposed at any time. We were always glad to leave. Unless you were required to go ashore, it was safer to stay aboard and stay below decks. The Mermaid left Palestine and our patrols in early 1947 and sailed back to Malta where we docked as usual in Sliema Creek. It was then that the crew found out that we were going two weeks leave whilst the ship was being painted again and all spruced up. One week would be spent in Malta and the other week in Tourmina, Sicily, right on the straits of Messina – alternate watches. After the two weeks, Mermaid left for Gibraltar. During this short voyage all aboard ship worked hard, or so it seemed, not the usual routine for sea. Everything was spit and polish. Something was afoot. We met up again with HMS Pelican again in Gib but couldn’t enter harbour. The following day, the answer to our wonderings became quite clear. All aboard Mermaid and Pelican were ordered into Number One dress and assembled on the upper decks, lined up for inspection and kept at ease for the longest of time. Still the lower deck ratings knew nothing or the reason for this. After awhile the buzz came around that there was a Battle Wagon in the straits heading for Gib. Sure enough, here she came, the biggest ship I had ever seen. It was HMS Vanguard, the Royal Navy’s newest ship coming up from South Africa, returning to Great Britain and carrying King George VI, the Queen Mum and both Princesses. She was stopping off at Gibraltar to drop off Princess Elizabeth who was going to Valleta to meet her husband to be, Lt Phillip Mountbatten RN and HMS Pelican was to take her with the Mermaid for escort. It was a calm, uneventful voyage and everything went well. Of course, appearing on deck it was always Number Ones and spotless, a far cry from our usual daily dress of the day. Needless to say, except for the duty watch, we mostly kept below decks and stuck to our usual routines. Things were quietening down a bit in the Med by this time, but the Mermaid went back to Palestine patrols again when we left Malta. We only caught up with one illegal vessel after that whilst I was still with Mermaid. I think the hottest spot in the Med at this time was at Famagusta, Cyprus where the illegal ships and camps for passengers were. The Mermaid just kept off the Palestine coast now and down as far as the Suez Canal area. I left the Mermaid in mid 1947 when we were just outside of Haifa to return to Portsmouth for demob, and it was a sad time I felt to be leaving, my home, my shipmates who were now part of me – Tom Buckland and Tom Bourne of number 9 mess especially. We were the three musketeers. When I left, I know the Mermaid stayed a little while longer in the Mediterranean. Lt Cdr Kimpton, our skipper, left and was replaced by Cdr Lennox who stayed with her until she was sold to Germany for a training vessel in 1948. (this news I have from a letter sent to my wife in 1964 from Sir Bernard Miles after we moved to Canada). It also states in the letter that the Mermaid’s bell now hangs in the foyer of the Mermaid Theatre in London as it was presented to the theatre by Admiral Lennox. The ship’s bell was rung by the Lord Mayor of London at the opening of the theatre’s season each year – a fitting end to a fine ship and to all who served aboard her.

|

|

Email Feb 09: Basil Bartlett served aboard Mermaid. His grandson is keen for any information that we can give him. If you know of this man, please can you email Rodney on r.bartlett -at- ntlworld.com. Replace the -at- with @ for a correct email address. May 09: Jenny Colclough emailed me: My late father Able Seaman Geoffrey Rowarth PJX521681 served on this ship and I was interested in finding out what he did. I don't know whether this name rings any bells with you. If my memory serves me right, as dad did not talk much about his war days, but I think he got appendicitis whilst on the ship and had to have an urgent appendectomy, not sure whether on the ship or somewhere ashore. March 2010: Urgent request for Jack Powrie to contact Len Elphick via the following email address: pjmosse - at - aol.com please replace -at- with @ for the correct email address. June 2011: My father William Henry (Bill) YOUNG served on the Mermaid during the Russian convoys, he didn’t talk much of his service and I would like to know if any surviving crew remember him and what his duties were, or any other information relative to his service - Vic Young - pamnvic2 -at- pg.com.au (swap -at- with @ to email Vic. April 2013: My father served on HMS Mermaid during the war and just after and I have been trying to find out what happened to the ships bell when the Mermaid Theatre, who were the custodians of it, became a conference centre. Do you have any idea where i could find this out please. Regards Jacqui Carter January 2018: My late father John ( Johnnie) Callender was part of the crew of the Mermaid during the war and i think he was present during the Arctic convoys, Malta, Venice and Palestine duty mentioned in the HMS Mermaid insight piece you co wrote. I was wondering if you had any information on him or could point me in the right direction in finding information. He was a CPO until the trip to Venice where i believe he missed the ship and got arrested for stealing a boat in an attempt to get back. He was a stoker and was also a geordie. If you have any information i would be eternally grateful if you could help. |

Walker RN - Click Here

http://www.naval-history.net

http://www.naval-history.net/xGM-Tech-Anti-submarine%20Weapons.htm

![]()

Maritime Disasters of WW2. My

first ever book - order it here - please? £11 only - click on the banner

Buy My WW2 Book here